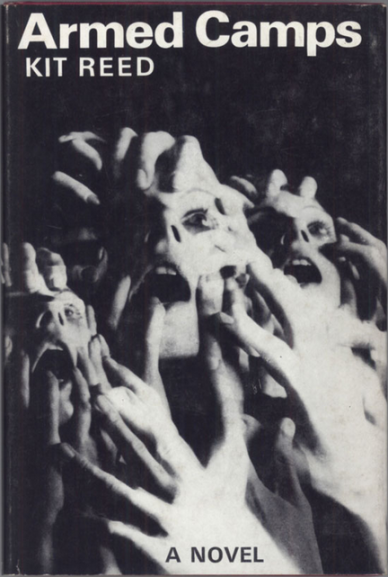

(Bob Haberfield’s cover for the 1969 edition)

(Bob Haberfield’s cover for the 1969 edition)

4.5/5 (Very Good)

“[…] and the men were on the way to the bar, they were talking about the performance, they had to compare it to every other performance, they had to link them all and form them into something continuous, something to keep away the dark” (19).

Kit Reed’s first SF novel Armed Camps (1969) is all about characters constructing narratives and conjuring visions in order to keep the aphotic tides of societal disintegration at bay. The two paralleled narratives — a woman (Anne) running from her past and a man (Danny March) slowly recounting what led to his own downfall — are two different ways of fighting off what is bound to come. An oppressive melancholy that never lifts soaks the passages, presaging the motions of the characters as if they are trapped in some Thucydidean manifestation of the cyclicality of history.

The style and content of Armed Camps is best described in context of the New Wave movement within SF of the late 60s and early 70s — but, it is worth noting that Kit Reed, unlike John Brunner or Robert Silverberg who had to radically depart from what they they had previously written (pulp) to construct their New Wave masterpieces, deployed a similar literary style in her first published works of late 50s. If you are interested in her earliest SF work I recommend the short stories collated in her 1967 collection Mister Da V, and of course, her recently published “retrospective” collection of shorts from her entire career as of now — The Story Until Now: A Great Big Book of Stories (2013).

Firmly a practitioner of social science fiction, Kit Reed has explicitly said in interviews that Armed Camps was her “why are we in Vietnam” novel [Tor.com article] — it is worth pointing out that the Tet Offensive, the largest military campaign of the war, was launched in early 1968. That said, unlike many anti-war visions of the period, I found Armed Camps a finely wrought commentary that does not resort to simplistic answers. Neither Danny March’s resort to terroristic violence nor Anne’s desperate adherence to pacifistic utopianism are presented as the way we can extricate ourselves from endless war.

Recommended for fans of New Wave and anti-war SF — and especially, for all fans of literary SF.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis (*some spoilers*)

Kit Reed’s dystopic near future Earth is mired with unrest. A sort of police state exists, and gun ownership is ubiquitous and necessary for protection: A government inspector proclaims in shock, “Of course you need guns, everyone needs guns” (64). Likewise, war has manifested itself in an almost allegorical form that illustrates its endless nature — a sort of single combat with flame throwers is waged between vast military bunkers.

Danny March was one of the best soldiers who flamed countless enemies (33). However, after an incident — that isn’t divulged until the end of the novel — March, after he’s found guilty, is trussed on a pole above a military installation as punishment. The military panoply of his ritualistic punishment is piped to America’s TVs. In March’s interior monologue he proclaims morosely: “You wonderful folks at home have all turned to some other channel, you tuned out as soon as the ceremony was over and they rolled the scaffolding away, you couldn’t ever wait for that final drum roll, you tuned me out and forgot me, just like that” (11). One of Reed’s central themes are the rituals that we adhere to in order to find some solace in a chaotic space: The ceremony of March’s punishment is one of many such rituals within the text. But Reed argues that there’s a rather more sinister edge to ritual — just as TV audiences changed the channel to order to avoid seeing the more mundane realities of March’s life while fastened to a pole, ritual can obscure a rotten core.

March’s life plays out as an attempt to break from the ingrained military ritual and the seductive (and meaning generating) forces of tradition. His father was a soldier, his father’s best friend was a soldier, his mother wanted March to be a soldier after his father’s death, the military wants March to sign over his son to the military…. March himself never had a childhood or someone to stand up for him — after his father’s death he has to “be the man” at a young age. However, he did find solace in the adventures of Captain White and “his dusky friend Hassim” (58) in the newspaper funnies: The Cap gets in trouble (but never dies of course) and Hassim comes and rescues him, repeat, repeat, repeat. As March languishes away his existence bound to his pole, he recounts how he found solace in the presence of Hassim. March, of course, is a stand in for Cap. Although never explicitly stated, Reed’s novel adeptly evokes the power that such stories had (and have) on youth — the ritual of reading, the stability of the plot, the simple messages.

The second narrative line follows Anne who is running from her past. As with Danny March, she is desperate to find meaning in her earlier actions. As she runs, she encounters others who have constructed meaning-forming rituals: e.g. at the Opera house, “men were on the way to the bar, they were talking about the performance, they had to compare it to every other performance, they had to link them all and form them into something continuous, something to keep away the dark” (19). Later she encounters Billy, who, along with throngs of other wealthy individuals, parties away behind walls that block out the chaos of the streets in an unfinished mansion (29). Billy’s mantra is an empty one — the shallowest possible — “Be pretty and dance” (31).

Eventually, Anne joins up with Eamon in Calabria. Eamon is a pacifist and Calabria is a series of ramshackle houses and barns located in a National Forest. He espouses radical pacifism and wants to believe that his idealism can be implemented. Anne buys into this vision completely but slowly observes Calabria fall into ruin…. Eamon himself, although the last to give up his own message, lashes out. And as Anne’s utopia crumbles she too is forced to confront what made her run.

(Richard Powers’ cover for the 1971 edition)

For more book reviews consult the INDEX

Great review Joachim, I’m still on the look out for that 1971 version with the gorgeous Powers cover.

I love the Haberfeld first edition cover as well. Matches the tone of the novel 😉

I’ll have to find a copy and read it. Thanks for the recommendation, Joachim.

Someone could do an interesting thesis or book on 1960s/1970s SF and the Vietnam War. There’s certainly enough material there.

You’re welcome! I had fun writing this review…

You know, I looked and looked and looked for a scholarly article through my University databases on SF and the Vietnam war and found very little…. I could, I could — if I wasn’t a medievalist 😉

There are, of course, descriptive type lists of works related to the war… But almost nothing analytical…

I found a few articles like these:

http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/pioneers/franklin52.htm

http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/sixties/HTML_docs/Texts/Reviews/Spark_VN_SF_New_Wave.html

Most are fairly polemical, even at this date. It’s fertile ground for academic study for someone who wants to try.

Thanks! I’ll have a look.

The Powers’ cover is as good as ever, but I love that Haberfield one.

I’m going to look out for this. I rather like the new wave stuff and this sounds very interesting in its exploration of ritual in various guises. Nice review Joachim.

Pingback: Armed Camps, Kit Reed | SF Mistressworks