Robert Foster’s cover for the 1st paperback edition

5/5 (Masterpiece)

Nominated for the 1965 Hugo Award for Best Novel [1]

Edgar Pangborn’s Davy (1964) takes place in a future devastated by a partially abortive nuclear war and the depravations of subsequent plagues (50). A powerful theocracy and perpetually warring microstates in the American Northeast emerged from the Years of Confusion. The novel takes the form of an autobiography. We follow a young orphan in love with life and desperate to escape his unfortunate circumstances.

Davy is organized around two parallel narratives of the eponymous narrator that interact in delicate ways with each other. In the present, Davy, fleeing across the Atlantic on the Morning Star after a failed attempt to reform the Kingdom of Nuin, writes about his childhood in an “obscure hope that in writing it I would come to understand it better myself” (229). He charts the events in his life that led him cast off the institutions that tied him to his home and a certain way of thinking: “If you’re sure there’s only one kind of truth, go on, shove, read some other book, get out of my hair” (42).

In the first sections, he recalls his first love, his encounter with a mutant in the woods, how he came across a golden horn, and his encounter with the survivors of a battle, including Sam Loomis who becomes his adopted father. In the process of writing, Davy experiences further trials and tribulations after his fellow dissidents establish a new colony in the Azores. This shapes and informs how he tells the later portions of his story, including his experiences with wandering musicians (Rumley’s Ramblers) and his meeting with Nickie, who simultaneously pulls him into radical reformist circles and her loving arms.

As the story progresses, how Davy interprets his own life, the future, and the autobiographical process shifts. A spectacular conjuration of character and the nature of storytelling emerges.

“Nuin is a Commonwealth, with a Hereditary Presidency of Absolute Powers” (13)

In Letter Bomb (1992), Peter Schwenger argues that nuclear fiction, to decipher the nature of the cataclysm, foregrounds the cryptic nature of signifiers of the long pre-nuclear past that the protagonists must attempt to read [2]. Jumbled references to historical events, geographic locations, and names demonstrate the extent of post-cataclysmic impact.

In an encyclopedic rundown of nations, Davy mentions how “every nation I know of except Number [The Holy City] is a great democracy” (13). Yet the governments he describes–with “hereditary” presidents, kings, oligarchies, and ecclesiastical states–are far from democratic [3]. Obliterating the meaning behind the cherished cornerstones of the American grand narrative serves to illustrate in small particulars how the world has changed but also how forces of collective stories can’t be entirely dislodged. As Davy reminds us, “I dare say no civilization completely dies” (134). We are reminded of its existence by “the stream of physical inheritance” and the “unrecognizable power” of “some word spoken a thousand years ago” (134).

A humorous example of historical muddling occurs after Davy joins Rumley’s Ramblers. Pa Rumley, the leader of the troop, avoids history, other than Cleopatra, whom he imagines that he would “have made out with her real smooth, if he could have met her in her native California when he was some younger and more ginger in his pencil” (239). No one can convince him that Cleopatra didn’t live in California.

An earthy and often violent medievalism permeates the pages. The Abrahamic Holy Murcan Church reads like a neo-medieval Catholic Church mutated only partially beyond recognition. This new aspiring theocracy revolves around a new prophet–Abraham the Spokesman of God, Abraham of Salvation also born like Jesus, to the Virgin, but in the post-apocalyptic wilderness in the Years of Confusion (22). Abraham dies, like most medieval martyrs, via an instrument iconographically associated with him, the wheel (22). As with the medieval period, the Church’s reach is only so far. It begrudgingly allows brothels (28), approves lusty and inappropriate art as long as it ridicules the past, preserves surviving documents in its own museums, and allows Rumley’s Ramblers to dodge requirements for priests to be present at the birth of an infant.

A Therapeutic Psychodrama and How the Past Really Works

Davy‘s format, an autobiography written over multiple years annotated with footnotes by his closest companions Nikie and Dion, is a unique set-up to allow a sustained rumination on the operations of narrative and memory. The novel serves as a therapeutic drama in which Davy reenacts, through the reflective act of writing, his journey from a “whorehouse that was not one of the best” (11) to the foundation of a new community of dissidents in the Azores and deaths that scar his very core.

Davy’s flight from the dogmatic truth of the Holy Murcan Church to an alternative way of viewing the world allows for an equally subversive formulation of textual truth and the malleable nature of the past. In one of the novel’s most insightful moments, Davy ponders identifies “four or five” different “varieties of time” within his story (49). There’s the main story that picks up after he leaves home at age fourteen. The story Davy lives while writing his autobiography–“whatever I write is colored by living aboard the Morning Star“–forms the second layer (50). This layer also interjects itself into the main narrative through footnotes written by Nickie and Dion. The historical asides that form the context for his life and world create a third variety of time. And the fourth, “the deep-hidden years before then, the age no one quite recalls,” are the events he can’t remember, those that cast a shadow that twitches and moves but cannot be seen (53). The non-sequential way of telling and conception of time creates associative meaning through the pairing of past memories with present events. There cannot be a simple truth to the past.

Through its non-sequential structure Davy, more than any other science fiction novel I’ve encountered, lays bare in beautiful ways the emotional experience of writing. Literary autobiographies often feel conjured as the product of a single moment of reflection rather than as organic documents written over months or years. Davy the man writing down his first memories of childhood is not the same Davy who writes of the death of Sam Loomis, the father he never had. He is alternatively frustrated and thrilled by writing. He deliberately delays telling his darkest thoughts and youthful sins. He dwells on sex and happy moments as they cover up the shadows that lurk beyond. The novel is an artifact of a therapeutic process.

“We Shall Not Have It All Mapped Before Sundown, Not This Wednesday” (256)

I want to write so much more. I’ve only touched the surface. It’s lusty. It’s smart. It’s structurally inventive. It’s beautifully told. It’s deceptive in its parts. It’s deeply emotional and intellectually stimulating in its ruminations on narrative and memory. As I immediately gravitate toward the moments that speak to my central interests, I’ve only mapped some of the novel’s territories. I’ve left for a later discussion–or someone else entirely–its animal metaphors of encroaching doom and earthy pastoralism.

Before I sign off, I hope other people write in more detail how sex-positive the novel feels (in distinctly 60s fashion of course). Davy reflects. “sex can be rowdy or brimful of moonlight: so long as it’s sex, and nobody’s getting hurt, I like it” (14). Some critics suggest that there’s the possibility that Pangborn might be gay [4]. While I don’t want to read too much into the sparse evidence, Pangorn does provide space within his stories for non-heteronormative relationships. While Davy enjoys his marriage with Nickie, he acknowledges how others might feel fulfilled with polyamorous relationships: “Adna-Lee Jason and Ted Marsh and Dane Gregory have chosen to build their house up on the hill […] That’s a love-alliance that began in Old City long before we sailed […] Adna-Lee has been happy lately as I never knew her to be in the old days” (133). He leaves open the possibility of a same-sex relationship between the Rambler musicians Bonnie and Minna, “They’d been making music together since they were […] babies, besides having a rare sort of friendship that no man could ever break out. I never knew whether they were bed-lovers” (202).

In addition, Pangborn acknowledges the societal forces that forced people to hide: “Pa Rumley was a little down on [sexual variation], I suppose hangover of the usual religious clobbering in childhood, so it was question you didn’t ask” (202). As Atterbery suggests, Edgar Pangborn “writes from an outsider position assigned by heteronormative culture, and he uses that position to critique social norms and institutions” [5].

Highly recommended for fans of science fiction that eschews the action-adventure template for character-driven reflection.

Notes

[1] Contains the following previously published sections: “The Golden Horn” (1962) and “A War of No Consequence” (1962). Both appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Somehow this majestic novel came second in Hugo voting after Fritz Leiber’s miserable The Wanderer (1964). Cordwainer Smith’s The Planet Buyer (1964) and John Brunner’s The Whole Man (1964) filled out the nominees.

[2] David Seed summarizes the main ideas of Peter Schwenger Letter Bomb (1992) in Under the Shadow: The Atomic Bomb and Cold War Narratives (2013), 3. I bought a copy of Schwenger’s dense book and hope to read it soon.

[3] See also the jumbling of democratic signifiers in William Tenn’s “Eastward Ho!” (1958).

[4] The notes on Pangborn in this 2009 Symposium on Sexuality in Science Fiction are worth reading. Brian Atterbery suggests that we “reset the controls on our gaydar, from ‘detect’ to ‘decode.’ Wherever his desires lay, and regardless of how actively or openly he pursued them, his work supports queer readings.”

[5] 2009 Symposium on Sexuality in Science Fiction

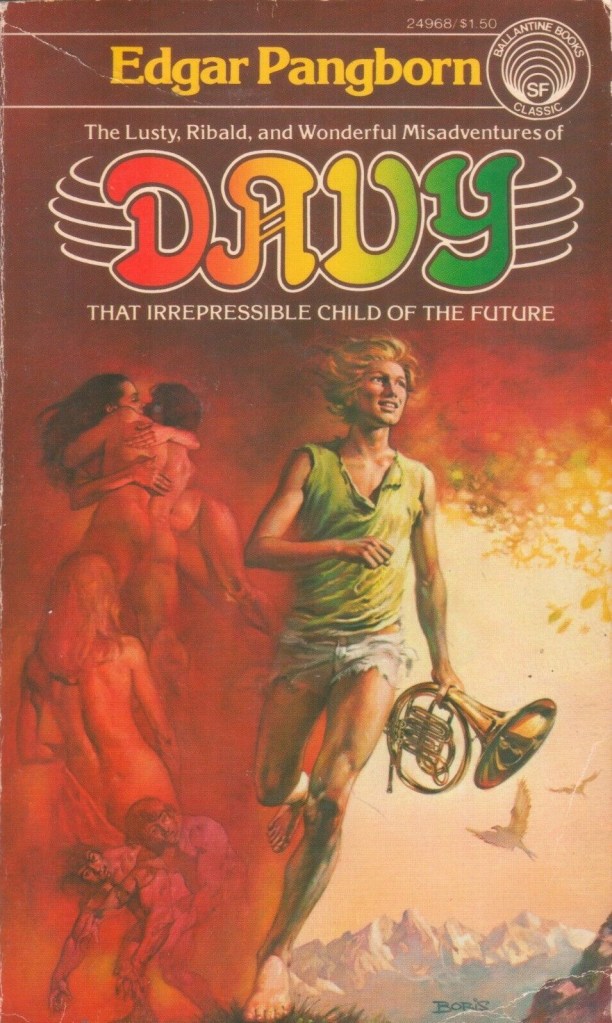

Boris Vallejo’s cover for the 1976 edition

Colin Hay’s cover for the 1976 edition

Franco Grignani’s cover for the 1969 edition

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

What an excellent review, the kind that makes one want to immediately track down a copy. The autobiographical structure, in particular, sounds very appealing to me.

Thank you for the kind words. Most reviews are far easier to write than this one! I finished the novel more than a month ago…

I’d put Davy on a very short list of novels from the 60s that should be read far more than they are. Definitely, the novel that should have won the 1965 Hugo over Fritz Leiber’s lackluster The Wanderer.

The Wanderer is awful. What were voters thinking?

I don’t know why Vallejo gave Davy cut-offs, as it is a plot point trousers are no longer a thing.

Those are some super skimpy verging-on loin cloth shorts! At least Vallejo narrows in on the lusty nature of the novel. And then the UK edition by Colin Hay (one of many Foss clones) thinks there’s been a new ice age… In the case of Hay, it’s probably art the press already owned and stuck on the novel without much thought. I don’t put much stock in covers.

Is Davy your choice (if we could retrospectively vote, muahaha) for the 1965 Hugo? I enjoyed Brunner’s The Whole Man but haven’t read the Smith… So maybe I shouldn’t be so presumptuous. But then again, it would be hard to find a novel that does so many things that appeal to me–specifically, the operations of narrative and history and memory and self-reflection.

The Smith is one half of Norstilia and while the Brunner has its moments, it’s really more of a fixup than a novel. So, yeah, Davy.

Re-the Smith. Yup! I own both. I don’t know which one I will eventually read. Maybe The Planet Buyers just so I can firmly say what’s the best novel of 1964.

Did you review Davy? What spoke to you about the novel? Davy also contained two previously published sections. That said, how the novel is organized allows for more episodic moments so it doesn’t feel like a forced fix-up.

I would say the best SF novel of 1964 is PKD’s Martian Time-Slip, although it was serialized in a somewhat different form the previous year as All We Marsmen and that made the longlist for the 1964 Hugo, probably rendering the book version ineligible for 1965.

I love Martian Time-Slip but I found this one superior. Again, the things that resonate with me (the operations of memory, self-reflection, metafictional engagement with way narrative works) are given serious space here — and that trumps a lot else in my personal summation.

Dick’s The Penultimate Truth (1964) comes to mind as well as a solid novel that year: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2012/06/27/book-review-the-penultimate-truth-philip-k-dick-1964/

And Dave Wallis’ Only Lovers Left Alive (1964)… although, I doubt that was on anyone’s radar other than in the UK. https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2021/10/14/book-review-only-lovers-left-alive-dave-wallis-1964/

1) DAVY was published in hardcover, was not an SF Book Club selection, and did not appear in paperback until too late for the Hugo voters to read it.

2) THE WANDERER was a Ballantine book, hence universally distributed, and Leiber was a prolific and popular writer, so very widely if not universally bought and read.

3) THE WANDERER is a very effective piece of fan-service pandering, telling a story that seemed familiar and comfortable to the hard-core SF readership–hey, it started off with an epigraph from E.E. Smith! I read it when it came out, when I was 15 or 16, and found it quite enjoyable at the time, though it has obviously diminished in retrospect. So it might well have won even if it had been timely mass-distributed.

Re-the particulars of Davy’s publication: Ah, that makes sense. I read somewhere that the vote was still close.

What is your pick for the year? Thoughts on Davy?

DAVY for sure. In fact, that was my preference in 1964; I got the book out of the library. I reread it at some point in the last two or three years and thought it was excellent, even better than when I first read it, and certainly Pangborn’s best. I read your review nodding along with it.

I’ve read two of Pangborn’s writings, a novelette called “The Music Master of Babylon”, which appeared in Galaxy, and A MIRROR FOR OBSERVERS, which was distributed by the Science Fiction Book Club. Both were very off-trail writings. I think Pangborn isn’t in the science fiction mainstream at all. He seems to write about the peculiarities of existence. Not that that demerits an author.

I have “The Music Master of Babylon” on my list to read. If either interested you, then Davy might be your cup of tea.

I’m so happy to see that you’ve done a review of this book. I think about “Davy” often, and especially the implications of the novel’s end. The sadness, the dread, and the inevitable aspects of life.

Davy didn’t know how to play the horn, so he made it up. I’ve always liked that adventurous quality in anyone. It matched well for me to his looming fate hinted at from the start, and the stories unavoidable collision with heartbreak.

What a great book.

Thank you for the kind words. It’s one of those novels that contain a lot of elements that speak to my previous academic life as a medieval historian. I studied the operations of historiography in the past. The feeling I get is probably the same as a trained scientist reading a correctly applied concept in a hard SF novel — haha.

Wanna say this is your best review that I’ve read in a long way. There’s a tangible sense of passion for the material. This review was under construction for a while and the effort shows. More importantly, it’s the kind of review that makes me wanna go back and reread the material, because I know I didn’t get all of Davy on a first read. This is not just a coming-of-age narrative—it’s that nestled within a larger narrative that reads like an actual autobiography from the future. Oh well, the Hugo voters went with the author who four times out of five WOULD be the right choice, but The Wanderer is bad lol.

I do think Pangborn was probably gay; his attitude toward sexual openness as expressed in Davy reminds me of Samuel R. Delany, who covered similar ground in the ’60s (and especially the ’70s), albeit with a more consciously literary bent. It’s not mentions of homosexuality and polyamory for the sake of it; these men imagined arrangements outside heterosexual monogamy because it was liberating, and to them it rang as true.

Thank you Brian, that means a lot. I still think the review needs polish. But, like Davy, I struggled with portions of this one — haha. It was preventing me from reading and writing about other stuff I want to dive into so I had to move on.

Spider Robinson, in that intro to Tales of a Darkening World that I DMed you, imagines that if Pangborn had his way, the end of The Judgement of Eve would have been a foursome. He’s extrapolating wildly of course but I think that does speak of his openness and, as you pointed out, the liberating possibility of sexuality in a more open society that’s manifest in a lot of his work.

The cover seems a trifle obscene, though.

I do describe the novel as lusty… Ehh, doesn’t bother me in the slightest. It speaks to its contents.

Have you read the novel?

The cover is art, what part is obscene?

A disfigured body.

That’s a character from the story, and it’s a good representation of his appearance. I like obscene, and anything that makes people say things like “that’s obscene.” I love that stuff and want more of it in the world. Artists of every kind should shake the world up as much as possible, and the more people they “bother,” the better. We probably don’t agree on this.

I think he’s just talking about the strange quantity of pectoral muscles Davy has.

No; I think obscenity is offensive to people, and that they should take offense. It’s a distortion of physical reality.

Uh huh. I was giving you a way out. Now it’s morphed into ridiculous non-sensical territory. Art does not have to represent “physical reality.”

But it has to be other than offensive.

Again, stop projecting on others. To you it might be. If so, I’m sorry you’re so bothered by a buff bodybuilder dude. You are not the arbitrator of artistic and moral value in the universe.

I see I dislike you. I’ll drop the topic.

I recommend not reading the book. It’s a steamy, occasionally–some might argue–homoerotic, radical 60s look at sex and sexuality (implied lesbian relationship, threesomes with two dudes, and lots and lots of sex etc.). You might be offended.

That’s the Ballantine edition, which announces on its cover that “Davy” is one of the ten best science fiction novels of the year.

Ah, the weird pectoral muscles? Well… who knows. To be honest, I tend not to focus too much on the art. It can be interesting but the texts are far more so in my view. As I pointed out above, the Colin Hay cover is deeply illogical and the Vallejo ignores descriptions of clothes presented quite early in the text.

I’m glad you loved it as much as you did! My main issues with it were the pacing was abysmal (imo), and I did not like any of the characters. I know you and I often read for different reasons (I have fewer qualms about leaning in to reading for entertainment, for example), and this may be one example! Great review.

I found the pacing isn’t created to push forward the story relentlessly — it’s dictated entirely by the mentality of Davy in the present. He dwells on what brought him happiness (the lengthy early interactions with Sam Loomis) and resists moving his story to the parts that he needs to work through to understand his more youthful self (the interactions with the Mue).

As for characters, I struggle to identify in my recent reading memory someone as memorable as Davy himself. He’s an iconic SF character in my view.

In A MIRROR FOR OBSERVERS a young man is being studied by people from another world. This could be similar to “Davy”. (I’ve only heard of two other Davys by way of storytelling, Davy Crockett and Davy Jones.)

Yeah, I’ve read a lot about A Mirror. I own a copy. I am more likely to read in the near future the rest of the stories and novels in the sequence that Davy is part of. https://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pe.cgi?1013

You mentioned having “The Music Master of Babylon” on your list. His first published SF story, “Angel’s Egg,” should be on it too if you haven’t read it. It’s much preoccupied with memory, though in a very different way from DAVY.

I saw that one recently in a magazine I was thumbing through. Again, I’ve heard good things!

Have you read both the magazine and novel versions of The Company of Glory? Spider Robinson in his intro to Still I Persist in Wondering states that all the homosexual content was excised from the Pyramid book edition. I just bought the novel so I’ll have to check.

No, I’ve only read the paperback of THE COMPANY OF GLORY. I was not captivated enough by the book to delve into its editing. Very readable and enjoyable, but the intensity of DAVY was mostly gone.

Thanks for this substantial review. It made me get my copy off the shelf and start reading. I haven’t gotten far, but I’m impressed. I owned a couple of Pangborn paperbacks in the 1960s and never read them before needing to sell them. Then a few years ago I read “Angel’s Egg” and “The Music Master of Babylon” and bought a handful of Pangborn’s books again. I read A Mirror for Observers, and then stopped. I meant to go on to Davy but never got around to it. Your essay has spurred me on. Thanks.

Thank you for the kind words. I look forward to reading more of his short fiction. I look forward to whatever you end up writing about the novel!

Reading DAVY inspires to write about DAVY. I went and read other reviews of it in F&SF, GALAXY, and ANALOG and like your review, all marvel at this work and want to say more. I believe your review describes the book best, but I wouldn’t have really understood what you said without having read part of DAVY.

This is an ambitious work. It comes around the same time as two other ambitious SF novels — STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND and DUNE. And DAVY has a lot of parallels with STRANGER. In 1959 there was a court case against censorship in a novel, I’ve forgotten which, which freed writers to write more explicitly about sex. I wonder if Heinlein and Pangborn were inspired by it. Sex is essential in both novels. Unfortunately, Heinlein botched his ambitious work. It’s strange that STRANGER is still read but not DAVY.

I will have a lot to say about this book if I can muster up the energy and discipline. But I’m glad you’ve started the discussion. DAVY needs to be reprinted and promoted.

There will be so much to say.

Good!

I definitely meant my “review” to be more an analysis article. And I’m not constrained by length on my personal website! hah.

I certainly prefer Davy to Stranger in a Strange Land–albeit I read it pre-site and the details are sketchy at best.

Davy is ambitious in a sneaky way so I don’t think it really had the impact that a more overtly ambitious epic like Dune had unless you dwell on its specific way of telling.

Great review. My main takeaway is that I need to reread DAVY. I read it when I was 15 or so and I liked it a great deal, but my memories are very fuzzy.

I look forward to your reread thoughts on the book!

Davy is a wonderful novel, a powerful example of what could still be done with the form in the middle of the twentieth century. It is as if Pangborn took all the sex and sensuality that was largely absent in the genre and packed it into this brief, lusty tale.

You note Peter Schwenger arguing that post-apocalyptic fiction “foregrounds the cryptic nature of signifiers of the long pre-nuclear past that the protagonists must attempt to read”. I like to think that it also expresses, in exaggerated form, just such a confusion in our “pre-apocalyptic present” in which we (which is to say me…) often fall into a daze confronted by the hieroglyphics of everyday life.

Your observation that Davy “lays bare in beautiful ways the emotional experience of writing” by way of conjuring the temporality of composing a (fictional) autobiography is a remarkable insight. It something I need to pay attention to on my next re-read, which isn’t far off now.

Thanks for this excellent review of the superlative Davy.

Thank you for the kind words. They mean a lot. I’ve been afflicted with a mild case of writer’s block and I’ve struggled this year with reviews more than I have in the history of the site.

I look forward to reading Schwenger. I imagine it is chock full of intriguing observations. If I’m not mistaken, Russell Hoban’s Ridley Walker is put forward as the most sustained example of this linguistic jumbling. I’ve been collecting, as you can probably tell, examples of the jumbling of American grand narratives of progress and exceptionalism.

Yeah, that temporality of composing is what really pulled me in. Especially the moments before he has to explain how he came into possession of the horn. His reluctance seeps through the pages. The transparent nature of the interplay of both narratives is absolutely brilliant.

You’re welcome. I was worried that maybe I had been too effusive in my love of Davy, but I feel safe in my opinion now that you have confirmed it so ably!

I dimly recall the narrative layering and am keen to revisit it.

I might have a peek at ‘The Judgement of Eve’ soon. Sadly, ‘The Company of Glory’ is not good–or at least I found everything after the first chapter not as good as the first. The short stories though I recall having a lot more fun with.

Thanks again for the recommendation on Davy (3 for 3 after Dying Inside and Mockingbird) – it met the high expectations, warrants your rating and the great review above. I’ve read my share of post-apocalyptic fiction but I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a Bildungsroman among them. Also unusual was the vestigial remains of the “Old Time”, with the exception of the horn, some of the place names and a statue of John Harvard. Perhaps this helps contribute to the “malleable nature of the past” as you say above. It does have a timeless aspect to it. Besides the medieval quality you allude, I sometimes felt I was reading a Western. Again, thank you.

No problem. It’s quite original for the era. I thoroughly enjoyed it!

Pingback: Year in Review - The Artistic Consolations of 2024, Part I: Literary