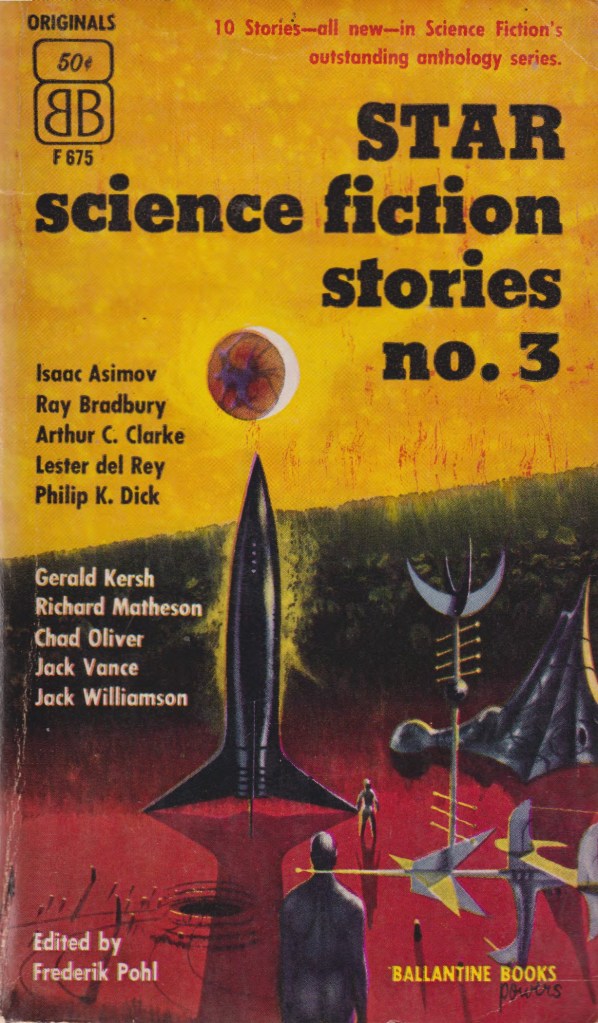

Uncredited cover for the 1983 edition

3.75/5 (Good)

Zoë Fairbairns’ Benefits (1979) charts the struggles of the British women’s liberation movement in a dystopic near future. An anti-feminist fringe political party called FAMILY comes to power, simultaneously proclaiming family values while systematically dismantling the welfare state. Benefits effectively eviscerates governmental doublespeak and champions the need to organize and educate in order to fight against patriarchal forces and messianic movements that promise to solve all our ills.

The Lay of the Land

The year is 1976. A massive heatwave rocks the UK.1 However, a seemingly innocuous policy will be used to plunge the country into nightmare. The plan? The British government promises to implement “weekly payment to mothers” (5).2 The titular “benefits” would move some earnings from the wallets of fathers into the purses of mothers. The problem? Confronted by a powerful male-dominated trade union movement attempting to protect its male workers, the government “flew in the face of its commitment to women’s rights” and postponed the scheme (5). Mothers decides to go on strike.

Continue reading