I can’t escape the post-apocalyptic wasteland. Like a voyeuristic shadow, I follow the denizens of the charred surface as they plod their slow movements toward the end. I observe how they push away the looming violent redness that blots out the sky, and, when everything else seems lost, they turn interior. A final movement that lays bare tattered dreams and ephemeral memories…

Ed Emshwiller’s cover for Galaxy Science Fiction, ed. H. L. Gold (November 1954)

5/5 (Masterpiece)

Edgar Pangborn’s “The Music Master of Babylon” first appeared in Galaxy Science Fiction, ed. H. L. Gold (November 1954). You can read it online here.

Fresh of Edgar Pangborn’s masterpiece Davy (1964), I decided to cover some of his short fiction on the site. He’s shaping up to be my author of the year. “The Music Master of Babylon” (1954), which I suggest should be included as part of his Tales of a Darkening World sequence due to multiple references to events and people present in the world of Davy, contains many of the embryonic concerns that crop up in the later novel. Pangborn is the master of interweaving narrative and personal memory and the ways art–in this instance music–lays bare the topography of self.

Memory, An Anchor. Memory, A Salve

In his old age, Brian tries not to remember his childhood. He fears he will “reject the present and dwell in the lost times” (83). But bits of the happy past interject into the post-apocalyptic now. “Bars of dusty gold” light peer into the Museum of Mankind in which he dwells, alone, that pleasantly reminds him of a “hayloft at his uncle’s farm in Vermont” (86). Pushing away the warming nostalgic allure, Brian instead constructs a lachrymose history of the cataclysmic events that lead to the seemingly empty world in which he dwells, an artifact of a world crumbling from view. The “places and dates” of the Civil War, pandemics failed interstellar missions, earthquakes, Soviet invasion, and atomic blasts serve to “impose an external order on the vagueness of his immediate existence” (84).

A refugee of a Soviet micro-state up the Hudson, Brian, a professional pianist who once performed for Abraham Brown, President of the Western Federation, arrived in the remains of New York. The ocean covers most of Manhattan, other than the Museum of Mankind connected tenuously to the mainland. Its bottom floors submerged, Brian set up residence in the cloakroom of the Museum, with a store of weapons and supplies. Brian spends his days hunting for food and keeping one Grand Piano in the Hall of Music in functional order. In a daily “sober ritual” of preserving the past, he tunes it reverently, dusts its surface, and covers it with stitched sheets (91). And at the Grand Piano, he plays The Project.

For Brian, the music of Andrew Carr, in particular his Piano Sonata, represents the tumultuous post-Hiroshima world. Born right after the bomb, Carr’s own chaotic existence represents the contradictions of the era: “He was a young devil-god with such consuming hunger for life that he had choked to death on it” (94). In the twilight of an era, Brian finally feels like he can play Carr’s visions as they were truly intended. And so he practices the “outbursts of savage change” and “unforeseen recapitulations” (95), a “final statement for a world that couldn’t live and yet was too good to die” (93). But soon two young teenagers approach the museum and Brian must confront the possibility of a new world.

The historian in me shivers with excitement whenever I encounter an author willing to dwell a moment on the complex nature of history. William Tenn’s “Eastward Ho!” (1958) immediately comes to mind with its, remarkably complex expose of America’s history of racism and conquest that subverts the canonical mythologized historical moments in the collective memories of all American school children. Pangborn pulls history into far more personal territory. Pangborn ruminates: “Biographies were like musical notation, meaningless without interpretation and insight” (94). The lachrymose past–filled with violence and suffering–Brian ritualistically recounts, serves to buttress the present and shape his internal conception of his own role as the last musician playing the most difficult work of the last great composer. He will only be able to recount it for so long. Soon his memory will fail and the Museum itself will sink into the sea: “Time was a gradual eternal dying. Time was a long growth of dirt and ocean salt, sealing in, covering over forever” (96). But there’s a new world out there, with its own memory constructions, and revisionist histories.

“The Music Master of Babylon” pairs nicely with Richard Matheson’s contemporary “Pattern for Survival” (1955), in which a pulp author sinks completely into a literary construct of his own making to escape the dying world around him. Both are well-told and filled with powerful images.

Highly recommended for all fans of ruminative 50s science fiction.

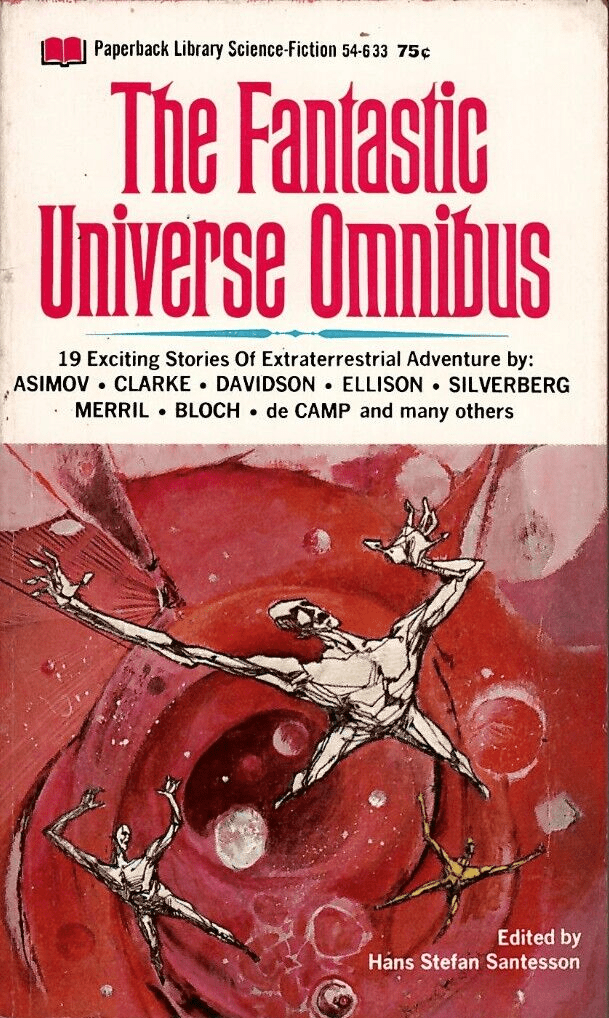

Jerome Podwil’s cover art for the 1968 edition of The Fantastic Universe Omnibus, ed. Hans Stefan Santesson (1960)

3/5 (Average)

Robert Silverberg’s “Road to Nightfall” first appeared in Fantastic Universe, ed. Hans Stefan Santesson (July 1958). You can read it online here.

According to Mike Ashley in Transformations: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970 (2005), Silverberg wrote his bleak cannibalistic nightmare in 1954 and spent four years finding someone willing to publish it. Unlike indirect references to cannibalism that characterized other 50s stories, Silverberg places it front and center. I am unsurprised it struggled to see print!

A somewhat effective 50s shock story, “Road to Nightfall” follows the army veteran, and specimen of hypermasculine vitality, Paul Katterson across the wreckage of post-blast New York. In 2050, after “twenty-four years of war with the Spherists that just about used up every resource of the country” (95), the US is crisscrossed by bands of radiation-inundated wasteland cutting urban center from farmland. New York relies on a few nearby urban oases like Trenton for food. Unfortunately, Trenton protests the “burden of feeding helpless, bombed-out New Work” and squirms out of their responsibility leaving the residents hunting scrawny dogs or turning to local “merchandisers” (93).

One of these euphemistically named human meat sellers, attempts to employ Katterson, due to his musculature and military training, as a procurer of flesh. He adamantly refuses. His girlfriend Barbara (also the name of Silverberg’s his first wife whom he married in 1956!) attempts to indirectly push Katterson to accept the offer. After another sojourn for sustenance in which he saw multiple civilians killed for meat, Katterson returns home to find Barbara sitting at a table eating a piece of meat with a man named Heydahl. Katterson, diving the nature of the flesh, proclaims “a choice of fat little boy?” (103) and suggests that she paid Heydahl with sex, before hurling it at Barbara’s head and fleeing the apartment.

The final act of the story follows Katterson’s interactions with a group of academics, including North who “still attempts to pursue knowledge at Columbia, once a citadel of learning” (106). They speculate on the nature of humanity’s plunge towards the end, munch of the remaining dole portions North squirreled away, boil the leather of books, and wait for the end. Katterson decides to leave the group and discovers the body of a recently dead man. Will he fall victim to the deep hunger that resides within him?

“Road to Nightfall” (1958) pushes its post-apocalyptic premise to horrifying ends. I was reminded of the presence of cannibalism within the grand narrative of the British colonization of North America–a 2012 discovery that made “The Starving Times” far more dramatic and disturbing. Silverberg can only grapple at the nature of apocalyptic destruction by suggesting the ultimate ending — humanity consuming itself. Unlike many of its ilk, no future world peers through the darkness. Possessed by a bland functionalism despite the power of the premise, it’s far from Silverberg’s best of the decade.

Somewhat recommended as a 50s shock story and fans of apocalyptic nightmare.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

“The Music Master of Babylon” also references a character from Pangborn’s great novel A MIRROR FOR OBSERVERS. (Andrew Carr, actually.) My feeling is that those references are not intended to make the story part of the continuity of either novel, it’s just Pangborn reusing names.

I read the story a couple of years ago, and I liked it, though I wouldn’t call it a full 5/5 story. I’d be interested to see what you think of A MIRROR FOR OBSERVERS, which I think is very very good indeed.

As for “Road to Nightfall”, I recall reading it decades ago, but all I can remember is thinking it pretty good for Silverberg’s early hack period.

The reason I saw “The Music Master of Babylon” as connected to Davy is that he provides an origin for the Abrahamic religion (the adopted parents of the two teenagers reused the name Abraham Brown, the President of the Western Federation, to create new new religion) that forms the basic of Davy’s world. Pangborn also references the wheel at Number (Newburgh, the capital of the small Soviet State formed after their paratroop invasion) where Abraham supposedly was martyred. That and the historical events that led up to the limited nuclear war… It seemed like far more than reusing names.

Ahh, Pangborn. A Mirror for Observers might be in my top 10 novel reads of the year. As for his short fiction I’m gonna savor it, since he sadly wrote so little. “The Music Master of Babylon” and several other of his short stories are also on Gutenberg!

Which other of his short fictions did you enjoy?

I am planning to review everything he wrote over the next few years — and even returning to his first novel that I did not care for and never ended up reviewing.

This is the first time I’ve read anything by Edgar Pangborn. He writes in a quite good prose, but I thought that was all. There didn’t seem to really be any plot or story and it was vague. I know there must be strong themes here, including about tribal religion, but like anything else here, I failed to appreciate it’s significance. It seems like typical 1950s SF. Sorry, but it didn’t do anything for me.

To be honest, I didn’t find anything about it vague. Just as Carr represents the final artistic moment of the pre-atomic war era (born right after WWII), the main character represents the last survivor of that period, and the performance of Carr’s piece is a swan song of an era. And the two teens represent the new generation with their own rituals, in part spurred by the performance of the Carr Sonata, albeit in new ways.

I think your thesis must be right, but I just don’t think I got it. I just couldn’t penetrate it’s meaning. Perhaps it was the style. Not everything will appeal to everyone in the same way. Glad you liked it.

Thanks for the post and the link.

Two different things — analysis of its message vs. appeal. I’m only contesting/debating the first. The second is something of a given!

Yes, of course.

“The Music Master of Babylon” is one of my all-time favorites. However, I didn’t note the connection to DAVY. Good call.

Have you read “By the Waters of Babylon” the story that inspired Pangborn?

Yeah, it’s a good one. I’m a sucker for a ruminative tale…

I have not read the Benet story — yet. I have it bookmarked.

Try to find “The Judgement of Eve” by Pangborn. Good stuff.

It is on the shelf.

Did you see my review of Davy? https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2023/07/29/book-review-davy-edgar-pangborn-1964/

Yes, Pangborn is one of my favorite authors. Unfortunately, I think he committed suicide, and his works never had their copyright renewed. I have a few other books of his, but I haven’t read them in years. Everything is out of print and not easy to find. I have searched for audiobook versions of Davy, and Eve, but all I could find were machine voice readings.

I write (very bad) SF novels, and in the latest I have a character named Nicky. I borrowed the name from Davy.

I liked Davy a lot, but I feel that the book was never really completed. It wandered about after a while, and then it just faded out. You admired it for the complex development of the story, but I would have been happier with a more straightforward denouement. “The Judgement of Eve” is a better novel. When I finished it, I put the book down and yelled, “Damn!”

I enjoy his work too. I own all his SF in paper form (and all the magazines are digitized online). Yeah, I thought Davy was the complete package and certainly not unfinished — it had a clear beginning and end and the various sections that might feel rushed are deliberate authorial choices that reflect back on Davy’s character.

I can find no evidence that he committed suicide. Where did you hear of that?

I can’t find any evidence either. I have it in my head that he killed himself, but now I think I may have been wrong.