2021 was the best year in the history of my site for visits and unique viewers! I suspect this increasingly has to do with my twitter account where I actively promote my site vs. a growing interest in vintage SF. I also hit my 1000th post–on Melisa Michaels’ first three published SF short stories–in December.

As I mention year after year, I find reading and writing for the site—and participating in all the SF discussions it’s generated over the year—a necessary and greatly appreciated salve. Thank you everyone!

I read very few novels this year. Instead, I devoted my attention to various science short story reviews series and anthologies. Without further ado, here are my favorite novels and short stories I read in 2021 (with bonus categories).

Tempted to track any of them down?

And feel free to list your favorite vintage (or non-vintage) SF reads of the year. I look forward to reading your comments.

My Top 7 Science Fiction Novels of 2021 (click titles for my review)

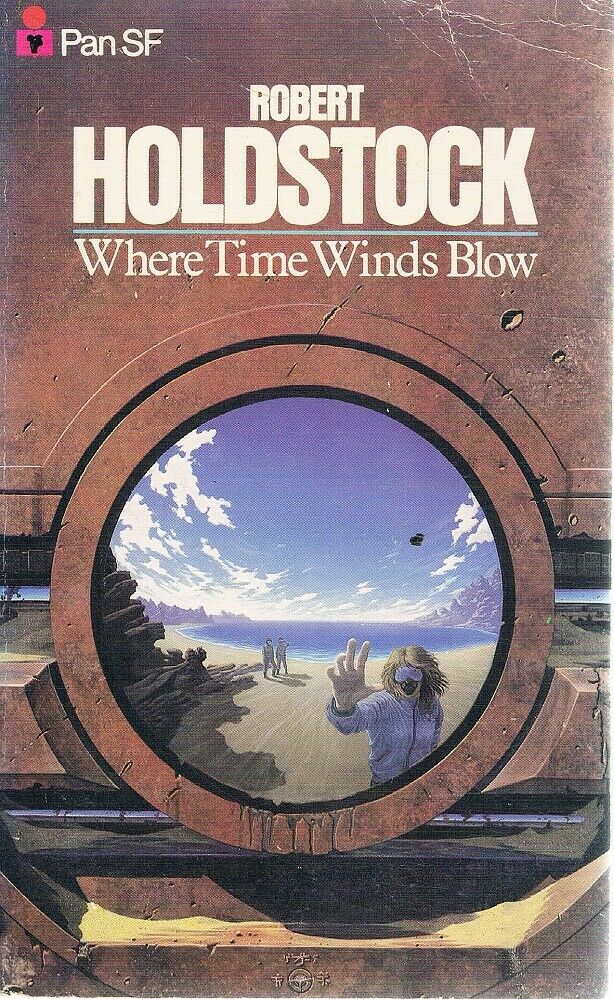

Uncredited cover for the 1988 edition

1. Where Time Winds Blow (1981), Robert Holdstock, 5/5 (Masterpiece): Holdstock’s vision is a well-wrought cavalcade of my favorite SF themes–the shifting sands of time, the pernicious maw of trauma that threatens to bite down, unreliable narrators trying to trek their own paths, a profoundly alien planet that compels humanity to construct an entirely distinct society… It’s a slow novel that initially masquerades as something entirely different. Just like the planet itself.

Continue reading