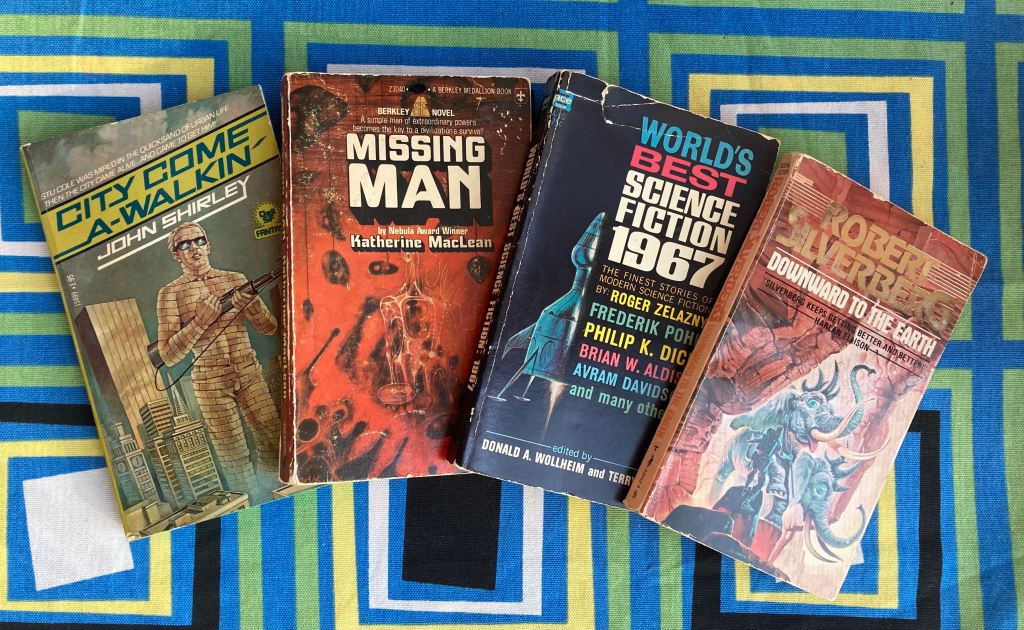

A selection of read volumes from my shelves

What pre-1985 science fiction are you reading or planning to read this month? Here’s the December installment of this column.

Lost texts, and the act of reconstructing the fragments, fascinates. The questions pile up. Would the contents reveal a pattern in an author’s work? Intriguing personal details? A startling modus operandi? At the 11th World Science Fiction Convention (Philcon 2), Philadelphia (September 1953), Philip José Farmer gave a speech titled “SF and the Kinsey Report.” Considering Farmer’s recent publication of “The Lovers” (1952), this is not surprising. Alfred Kinsey, the famous sexologist and founder of the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction on Indiana University’s campus, published his controversial Sexual Behavior in the Human Male in 1948. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female appeared in 1953. Like many of Farmer’s earliest speeches, he did not keep copies.

Deeply intrigued by what the speech might have contained, Sanstone and I (on Bluesky) managed to piece together a few general responses from fanzines and magazine con reports.

Continue reading