Along with Octavia E. Butler (1947-2005), Samuel R. Delany (1942-), John M. Faucette (1943-2003), John A. Williams (1925-2015), and Steven Barnes (1952-), Jesse Miller (1945-) was one of a handful of African American science fiction authors active in the 1970s (note). I have confirmed with Jesse Miller’s relatives that he is still alive. I initially, before confirmation, extrapolated his birthday from a quote in his author blurb in Orbit 16, ed. Damon Knight (1975): “I am black. I am twenty-nine, and I have a good sweet woman, whose name is Jean, and I am slowly going blind.”

Soon after his honorable discharge from the United States Airforce at 21 (after service in Vietnam?), he published four short stories between 1972 and 1979 and then left science fiction altogether. One of a legion of authors first published by the late Ben Bova, he was a finalist for the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer (renamed the Astounding Award) for his first published science fiction story “Pigeon City” (1972). He lost to Spider Robinson and Lisa Tuttle. He wrote his first story (published later in 1975) while in a VA hospital bed. For a bit about his life, his brief experience at SF conferences, reflections on losing the Campbell Award, and various humorous and serious interactions with other authors (he smoked a pernicious strain of weed with Joe Haldeman), check out his article “Obnoxia” (c. 2001). I’ve also included George R. R. Martin’s recollections, as recorded in his intro to “Twilight Lives” (1979), in the review of the story below.

Theodore Sturgeon penned the following about Miller in his intro to New Voices II, ed. George R. R. Martin (1979): “[Miller] has that rather rare gift of writing “there,” of giving the reader the feeling that the writer is on location and not operating on a built-up set. Jesse Miller will go flap-jappering up to a high place or he will disappear.” It’s a loss to the field that the latter happened. Three of the four short stories are worth the read! And “Pigeon City” is a near masterpiece that should be anthologized more widely.

If you happen to know any more about him, please let me know!

Note: I think this is complete but I could be missing someone. Steven Barnes published his first three short stories in the 70s. I know Charles R. Saunders’ early work appeared in 70s genre fanzines. Did he write any SF or was it all sword and sorcery? I considered leaving John A. Williams off this list as he’s known as a mainstream author. His wonderful novel Captain Blackman (1972) could be classified as a speculative fiction involving time-travel (whether or not its entirely metaphorical). Williams’ Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light (1969), which I purchased recently, tells of near-future race violence in New York City. I think he qualifies.

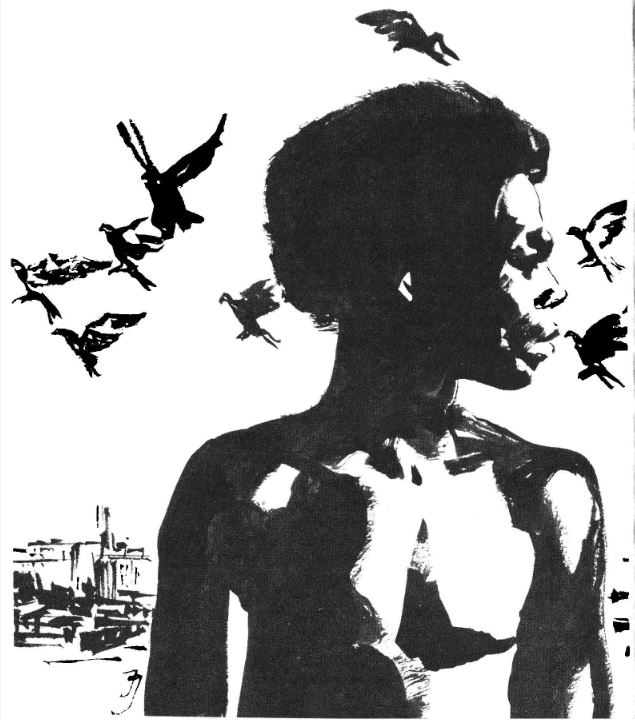

Jack Gaughan’s interior art for Jesse Miller’s “Pigeon City” in Analog Science Fiction (November 1972)

“Pigeon City” (1972), 4.5/5 (Very Good): First appeared in Analog Science Fiction (November 1972), ed. Ben Bova. You can read it online here.

In the 1950s and 1960s, white Americans propelled by racism and economic reasons fled the urban centers for the suburbs. According to Leah Boustan, for every “black arrival, two whites left the central city” in Northern and Western metropolitan areas. An insidious cultural iconography of middle-class white suburbia, replete with lawn and single-family houses, perpetuated inequality and excluded others from the American Dream. In this period, major race riots broke out across the United States–New York City (Harlem Riots, 1964), Los Angeles (Watts Riot, 1965), Newark (1967), and Detroit (1967)–in protest of poverty, racism, and unemployment exacerbated by the departure of businesses from the city centers.

Jesse Miller’s disquieting “Pigeon City” imagines a Harlem of the future where similar trends continue—racial enclaves become utterly isolated from the exterior world. The “city machine” (88), now controlled by computers, provides food, supplies, and retribution to the increasingly dilapidated and forlorn “ghettos” (94). There are no jobs as basic necessities are provided by the city. Curtiss and his fellow black denizens of Harlem while away their time absorbed in their hobbies–Curtiss with his pigeons on his roof, Franklyn making candy perpetually lodged in his mouth, and Allen planning for a way to get back at the machine. Telling time has fallen out of fashion (93) and Allen’s public revolutionary antics promise “real entertainment” and a break from the endless monotony (92). Everyone is deeply suspicious of Allen as in the past he had built a bomb and his accomplice Irene was whisked away in an act of “heavier retribution” (94). Her fate unknown. Filmic sequences of past riots are spliced with propagandistic proclamations—“a white voice intoning off camera while the horrible scene was enacted: ‘This is the fate of the greedy, the destructive, the ignorant…'”–to keep the “ghetto in line” (94).

Allen, decked in his “dashiki” (92), conspires to create the biggest explosion and fire in the city pulling Curtiss and Franklyn into a confrontation with the real power behind the scene. After the destruction of an automated fire engine, rapid response vehicles gas the protestors reveling in their momentary victory. 76 protestors awake in a room with a gigantic screen relaying cryptic orders and tests. Options are provided. Paths are given. And soon, a rather more complex and sinister bureaucracy reveals itself.

“Pigeon City” puts a distinct twist on common SF themes of automation and urban decay. This is a surreal nightmare of segregation pushed to the extremes. And Miller’s prose exudes a calm realism that pulls you in as if you stood on the streets watching another world spin past. I struggled a bit to identify the ultimate message of the story. Does it convey the disturbing conundrum that African Americans who managed to leave their segregated communities experienced when they found themselves in yet another segregated world? Curtiss and his friends find themselves a way out. But is it a way out at all? And is the new world any better than the old?

Recommended.

Note: Jack Gaughan’s interior art introducing the story is downright lovely. I might purchase a copy of the November 1972 issue of Analog to make some proper scans!

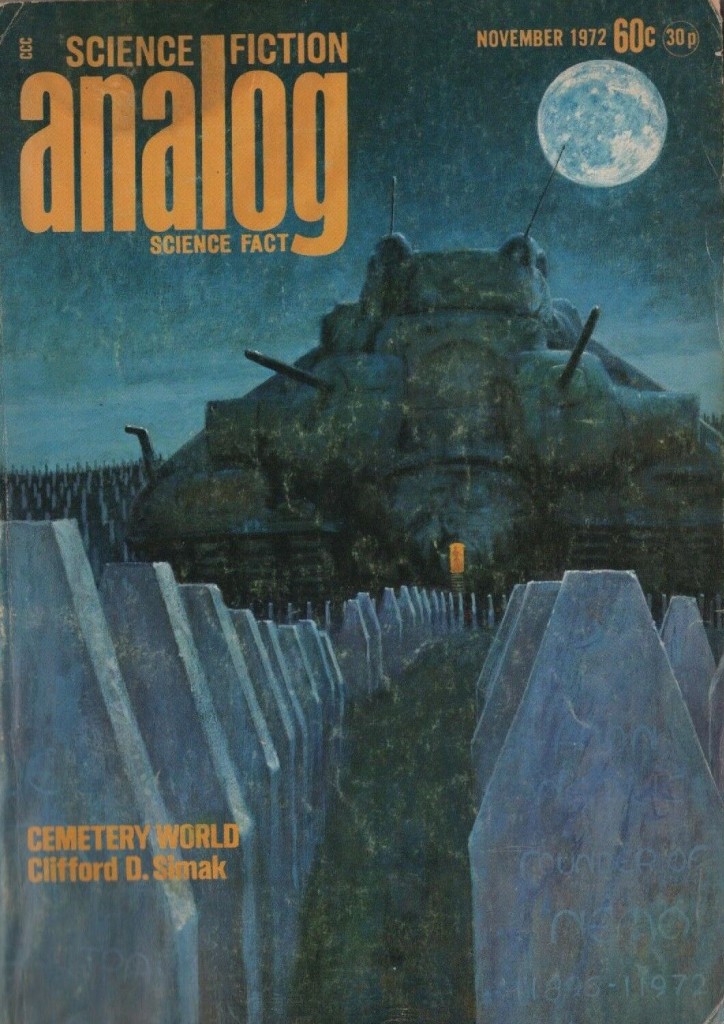

John Schoenherr’s cover for Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact (November 1972), ed. Ben Bova

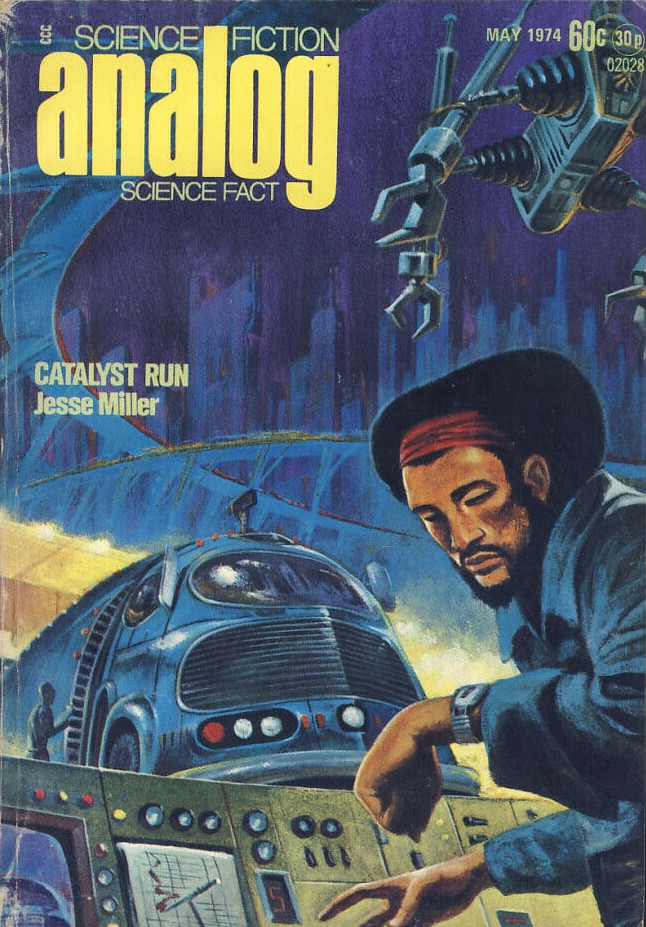

Jack Gaughan’s cover for the May 1974 issue of Analog Science Fiction, ed. Ben Bova

“Catalyst Run” (1974), 3.5/5 (Good): Only appeared in the May 1974 issue of Analog Science Fiction, ed. Ben Bova. You can read it online here. Into the minds of the compulsive we plunge…..

In a world without work, the few manual jobs that exists offer glamor and excitement. And everyone wants to work at the Detroit terminal, packing and unpacking crates, fixing engines, filling manifests, loading trucks. But really, everyone sweats and competes on the warehouse floor to be seen by the omniscient Sid, ensconced in his observation tower, to prove to him and the company bosses that they have what it takes to operate the rigs that navigate the partially automated interstates.

All is ruled by the Catalyst System: “you were at the top, or you weren’t” (15). And the company fosters and guides the races between the operators across the American expanse to “produce new records, innovations” and death (15). John Gutley’s at the top. His cruiser, the Luta, accumulates the detritus of the road like a totemic invocation of victory. Each new layer of grime, a new rival unable to climb to the top, unable to dethrone the king. Gutley eschews the techniques of the young. He refuses new innovations and does not partake of the Road Drug. Richard Arvius “kept his cruiser gleaming, and deep with wax. [Janice] was blue, and her metalwork sparkled wickedly” (15). Everyone knows Arvius will eventually dethrone Gutley. Deep in the swirling energy of the Road Drug that all the new generation swill like beer, Arvius races across the roads with Gutley on his tail rummaging through the memories of his past. Driving with the Road Drug in your veins brings a trance state pulsing with primal desires. But Gutley, against his character knowing that his end is nigh, has taken on an innovation for their race. His ace of spades. And terminal workers like Phillips angle for their own chance at the road exchange money and bets. And soon Arvius will become Gutley. And Phillips will become Arvius. And Gutley will join the legions before him who let themselves be ruled by the Catalyst system.

“Catalyst Run” presents a dystopic world where facilities like Amazon warehouses are the only places left to work. Of course, only the most compulsive of individuals are drawn within and let themselves be manipulated by the company bosses behind the scenes. Miller weaves gorgeous sequences. In one instance, Gutley watches his new rig conjured by almost priestly mechanics. He recalled “wondering at the fact that they all wore glasses, their pencils were always sharp, yet no one ever seemed to sharpen them, they all seemed to have clipboards, and their immaculate lab coats never got dirty” (29). Like driving long hours through a rainstorm in the American west, “Catalyst Run” takes on a ritualistic thrumming as the cycle resets.

Uncredited cover for the 1975 1st edition

“Phoenix House” (1975), 2.75/5 (Vaguely Average): Only appeared in Orbit 16, ed. Damon Knight. You can borrow it for 1-hour increments here. Damon Knight writes the following about the story: “This story was written in a VA hospital; it is his first, although others were sold and published earlier.”

A few hundred survivors of a nuclear disaster “led nomadic lives, scattered throughout the world” (131). After a period of infertility, Children are finally born who “remembered nothing but their own lives” (131). Everyone else is tethered to the past. One of those is Jake, who wanders the deserts of Nevada keeping a diary about the people he still remembers (131). He speculates on nuclear war as “an act of nature” designed to sheer the world of excess people (131). He buries dying survivors who wander into his camp, which he dubs the “Phoenix House.” From the wastes come mutants, also propelled to lead solitary and nomadic lives, clash with the humans they encounter. Spinning pithy pseudo-philosophical maxims, Jake is convinced of his own wisdom. But a new way of knowing must be wrought.

A vehicle arrives at his camp with a mutant named Ta Chaunce behind the wheel, with eyes “hard orbs of electric sparkle. Greenish, now blue…” (134) and telepathic projection that chants her name in his brain. Drawn to his shack due to “the feeling of age and solitude,” she momentarily overwhelms him with her telepathic presence (137). Jake fights back with fire. He returns to the injured mutant, evolved to exist in the harsh new territories, and nurses her back to health. And a delicate entendre is reached.

Stories with mutants and telepathy rarely resonate with me. Miller’s prose, as always, is solid and the scenes vivid. Miller’s own hospital experiences, adapting to a new world, reaching a point where he is able to put the next foot forward, adds a layer of meaning but the pieces are not interesting or memorable enough to create a cohesive whole. I found “Phoenix House” Miller’s least successful fiction.

H. R. Van Dongen’s cover for the 1st edition of New Voices II, ed. George R. R. Marin (1979)

“Twilight Lives” (1979), 4/5 (Good) only appeared in New Voices II, ed. George R. R. Martin.

For the sake of gathering together as many bits about Miller as I can, I’ve quoted GRRM’s recollections in his intro to the story:

“[He] first broke into professional print in the November, 1972 issue of Analog with a memorable novelette titled ‘Pigeon City.’ That was only one month before the appearance of the first short story that I’d sold to Analog, and a short time later I found myself in New York City dropping into the office of editor Ben Bova trying to sell him some more. Jesse was there too, and Ben took us both to lunch at a restaurant in the cavernous depths of Grand Central Station. Over drinks, I happened to mention the John W. Campbell Award to Jesse–who had never heard of it–and Ben and I both predicted that ‘Pigeon City’ would probably make him a contender for the honor. […]

Miller didn’t win the Campbell Award, but his reputation continued to grow, spread by stories like “Catalyst Run,” and Analog cover piece, and “Phoenix House” in Damon Knight’s prestigious Orbit series. Now living in Saugerties, New York, after leaving New York City, Jesse has recently completed his first novel, and he continues to write in both long and short lengths.

‘Biographically speaking,’ he writes, ‘I am changing biologically. I don’t know about spiritually. I feel like I have a whole lot to learn. I am very interested in telling anyone who wants to know anything about me whatever it is, if I can/ For this reason, I would like my biographical information to just say that I can be reached c/o FAMILY, in Woodstock, New York.”

And now on to the review!

“Twilight Lives” bites and claws like some feral rodent caught between the soft palms of your hands. In a post-disaster world without fossil fuels ruled by warrior women and scurrying with strange insects, the illiterate Cassidy rides his ten-speed tricycle to market. He’s eager to learn about the world from the women who stop by the stands who are able, unlike men, to travel from place to place. Not only do they represent knowledge, they also bring with them the “ability to hang on” in the downtrodden world where most men are not able to reproduce. And, as a eunuch, Cassidy yearns for company and conversation (1985). He’s possessed by deep jealousy of Harold Staples, an inventor able to have “sex with the travelers”(188), and dreams of a fetus in a tube that he can carry around his neck like the mechanic Hadner (191). In this twilight existence, Cassidy moves and watches and suffers.

And soon Yvette Mohammed arrives in town with her retinue. Cassidy’s memories of their previous interactions are unclear. There’s trauma behind the mist. In a confluence of events involving the beforementioned insects, Cassidy rescues a woman named Roxanne from the wreckage of an attack. And soon Yvette’s machinations of power are laid bare.

This is a hard read. I felt deeply for Cassidy, formed and shaped and manipulated by his cruel path and place. I cringed at his proclamations of Yvette’s morality and good intention: “Don’t talk about her in any but the most respectful way, all right?” (212). His sad outburst, “I feel like I’m being used, but I don’t know how” cuts to the true heart of things (215). Like a firefly placed in a jar flitting and blinking for a world beyond the glass, he too, will soon flicker out.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

This is a great find. I’ve never heard of Jesse Miller, though to be fair I never went looking.

I’m struck by the sense of overwhelming disorder: whether by the decay and destruction of the social bond, or its tighter and more exclusive organisation. That we’re living in the realisation of the latter version, and teetering on the brink of former version is testament to something–still caught in the dreams and nightmares of the past.

I think that’s a good way of summarizing the general feel of the stories. As you said, the four stories as a whole do convey a sense of overwhelming disorder — and, in the case of two of the stories (“Pigeon City” and “Catalyst Run”) cyclical disorder. All of his narrators are trying to flail around transformed worlds where the past offers no real solace.

I enjoyed them. Especially in the case of “Pigeon City” its engagement with issues of racial segregation and protest.

Has quite a good style of prose, but it couldn’t sustain the one I read, “Pigeon City”, through to it’s end. I found it hard to read and know what it was about. It’s imaginative strength was weak I thought. I suppose you see it different to me. I haven’t read him before.

I agree that it might have been on the long side. However, how he’s engaging with contemporary issues of the day and the ultimate nature of the parable elevated the story for me — and of course, his prose as well.

It is on the long side, although I did finish it to the end. I suppose it does deal with contempory issues of the day, but it could have been done more clearly and concisely I think.

“Twilight Lives” bites and claws like some feral rodent caught between the soft palms of your hands.

Dr. B! Go ON with your bad self…you broke into lyricism there. Good reviews all, even if the one read disappointed.

Thank for the kind words. Haha, yeah, I can’t help myself.

My personal favorite line from the review: “Like driving long hours through a rainstorm in the American West, “Catalyst Run” takes on a ritualistic thrumming as the cycle resets.”

Oh oh and this one: “His cruiser, the Luta, accumulates the detritus of the road like a totemic invocation of victory.”

Tempted by any of the stories? I can’t tell from your comment if you’re referencing the one I was disappointed by or that you read one and didn’t care for it.

Probably not going to read them. I’m never going to live long enough to read things I’m champing at the bit to get to; adding others means I need to feel black-hole levels of metaphysical gravity. Miller’s stuff ain’t doin’ that to me. Besides, I now know what I’m likely to think.

I somewhat know the feeling — I have a good decade and a half of unread books.

Assuming I live to 75, and am reasonably compos mentis until shortly before I die, and continue to average the paltry 175 books a year I’m averaging, I’ll read 2,275 more books before shuffling to my reward (eternal silence and blackness, I hope).

I presently possess 8,298 books.

The math is not encouraging.

I grew up in a house full of Analog science fiction books. My dad subscribed through the 1960’s and early 70’s. Analog was my first taste of science fiction.

Thanks for stopping by! Do you remember reading any of Jesse Miller’s fictions?

I believe I read Pidgeon city along with Cemetery World in the November ’72 analog. Only vaguely remember it though – don’t think I ever read it a second time.

I remember the cover from the next analog so I may have read the story but it did not stick with me.

I’m generally not a fan of Jack Gaughan’s SF art — but his illustrations for Pigeon City are top-notch.

It seems that Jesse Miller was another writer, and they are common in sf, that wrote a paltrey amount of fiction, then disappeared. Whatever happened to that novel that was mentioned? Alas, it’s been forty-two years since his last appearance and now we may never know what happened to him and all that he was working on. Maybe some enterprizing publisher will put all four of his known works together as a collection so his name won’t be entirely lost.

I think that’s why I find the Sturgeon quote I included so sad: “[Miller] has that rather rare gift of writing “there,” of giving the reader the feeling that the writer is on location and not operating on a built-up set. Jesse Miller will go flap-jappering up to a high place or he will disappear.”

Do you know of any other authors who wrote one or two solid to great stories and then disappeared? Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like Miller had time to hone his craft.

Well, we’ve both talked about Mari Wolf, then there’s A. J. Deutsch, who wrote only one story (“A Subway Named Mobius”), William Oberfield (whose “Poison Planet” has been translated into Spanish and Turkish), Leslie Perri only wrote three stories before fading away, and her story “Space Episode’ was, I think an early feminist space story. Helen McCloy is primary known for her mysteries but she wrote “The Last Day”, long before the story “Testement”, about a woman who watches the world die in an atomic war, then her family, then has to come to terms with her own oncoming death. Francis Stevens is mostly known for her fantasies, but she wrote the feminist “Friend Island” dealing with an alternate world run by women. Something like Tiptree’s “Houston, Houston, Do You Read”, but without the vile bile that Tiptree put in hers. This is just of the top of my head, then there are the writers that put out a lot of fiction but never had a collection put out and who are now forgotten.

Hay Dr. B! I got here via my BookRiot SFF newsletter, “Swords & Spaceships”! Yay for you!

Cool! Ah, what did the newsletter say?

Under the Weekly News & Views section, the link had this text: “Reviews of the short stories of Jesse Miller, a Black SFF author active in the 1970s”

And that, being as you’re the only weirdo weird enough to review such a thing, was all I needed to get me to click the link!