Chan Davis (1926-2022) was a fascinating figure. He was a communist activist, fanzine editor, mathematician, and political prisoner. He was fired from the University of Michigan in 1954 and imprisoned for six months in 1960 on charges of contempt of Congress leveled by HUAC. The Hugo Book Club recently posted a fantastic interview, from which I derived the bibliographic blurb above, with Steve Batterson, the author of The Prosecution of Professor Chandler Davis: McCarthyism, Communism, and the Myth of Academic Freedom (2023) that I plan on purchasing soon.

Today I have selected three of Chan Davis’ thirteen published SF short stories. The connecting theme? 1940s speculations on nuclear war in the immediate post-Hiroshima world. All three appeared in Astounding Science Fiction under the tutelage of John W. Campbell, Jr.

William Timmins’ cover for Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (May 1946)

3/5 (Average)

“The Nightmare” first appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (May 1946). You can read it online here.

A few months before the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima (August 6th, 1945), a group of scientists at the University of Chicago published The Franck Report (June 11th, 1945). James Franck and his colleagues argued that “within ten years other countries may have nuclear bombs, each of which, weighing less than a ton, could destroy an urban area of more than ten square miles.” They point out the great disadvantage of the United States with its “agglomeration of population and industry in comparatively few metropolitan districts” in comparison to countries with a population and “industry […] scattered over large areas.” In the months after Hiroshima, Chan Davis published his first SF story “The Nightmare” with The Franck Report warning firmly in mind [1].

Dr. Rob Ciccone, chief of the Bronx Sector Radioactive Search Commission, spends his days overseeing attempts to detect smuggled radioactive material in his district that could be used to create a small nuclear warhead. Despite his position, at one point he fervently opposed the search system as a preventative measure and believed that decentralization of America’s industries and population is the only to avoid the cataclysmic impact of a nuclear war–even one waged with small, locally made, warheads (8). Ciccone soon realizes that there’s a plot afoot to discredit the search system entirely, and drag him down with it. Or, there really is evidence of a sinister project to create a nuclear bomb inside of New York! But who’s behind it all?

“The Nightmare” reads like a near-future thriller periodically dragged down to a snails crawl by scientific lectures between characters: “What if, instead of natural uranium, you were to use Pu-239, ordinary plutonium, in your phosphorescent paint? It’s an alpha-emitter with long half-life, like common U-238; our instruments couldn’t tell the difference” (15). Considering the new and terrifying nature of nuclear war, I am unsurprised the lengthy digressions occur–I imagine readers captivated by the science behind the destruction. Davis’ conjuration of paranoia and secret plots and counter-secret ploys and new and terrifying ways to deliver death, immediately called to mind the stark warning of The Franck Report. The story’s final lines–“our magnificent, overgrown, bungling civilization going on its own magnificent and senseless way because it is so big that nothing can stop it, so big that it can’t even stop itself”–foreshadows a terrifying inevitability of future conflict even at a moment when the dust of WWII had barely settled (24).

Recommended only for fans of the very first speculations on nuclear war in the immediate aftershocks of Hiroshima. I suspect that you must be interested in the larger historical context (me!) to enjoy this particular story. Check out Theodore Sturgeon’s “Memorial” (1946) as well. Both suffer from a reliance on extensive informational lectures delivered between characters.

Notes

[1] Martha A. Bartter in The Way to Ground Zero: The Atomic Bomb in American Science Fiction (1988) briefly points out the connection between Davis and The Franck Report, 122. She does not indicate the Report’s warning about the US’s dense population which forms the conceptual crux of Davis’ story.

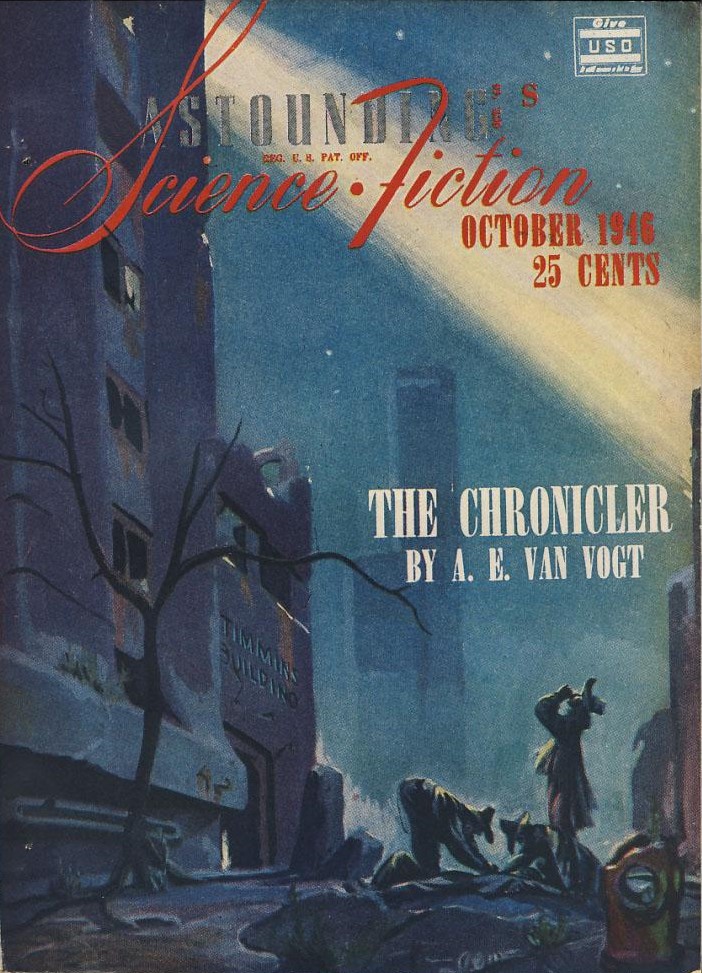

Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (October 1946)

3/5 (Average)

“To Still the Drums” first appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (October 1946). You can read it online here.

Chan Davis’ second published short story also takes the form of a near-future thriller. In 1948, with “the war […] quite definitely over” (159), Coleman Weiss finds himself stationed at a military base in Redcliff, Colorado developing experimental rockets that could carry nuclear warheads. In an innocent letter exchange with his long-distance girlfriend Kathryn, she points out that “about two and a half lines of your last letter were cut out by the censor” (159). The lines in question? Hypothetical musings on the possibility of a “military clique to get the United States into war against the wishes of the people and Congress” (169).

Coleman, initially, does not believe the paranoid fears of his co-workers on the project that the military is hiding something and instead parrots the official line: “we’ll have weapons so powerful nobody’d dare to start a war. Civilization will be more proof against wiping-out than before” (161). But the pieces start to fall into place and Coleman jumps into action. There is a plot!

I suspect “To Still the Drums” was inspired by Davis’ fear that the military would ignore the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (passed Congress July that year), that placed “nuclear weapon development and nuclear power management would be under civilian, rather than military control” under the United States Atomic Energy Commission. Davis, through his characters, ruminates on the terrifying new Cold War mentality that forgets the immediate past: “Hiroshima didn’t even make a dent in the Congressional consciousness, and it made the wrong kind of dent in the military consciousness” (165). Politicians ignore its human impact and the military imagines greater and greater weapons and dreams of using them. While Coleman’s actions prevent disaster in the moment, Davis leaves open the possibility of nuclear war: “ten years from now will the cities’ crowded millions be dissolving in rapid-fire bursts of flaming hell?” (1972).

As with “The Nightmare” (1946), I only recommend this one for fans of the very first speculations on nuclear war in the immediate aftershocks of Hiroshima.

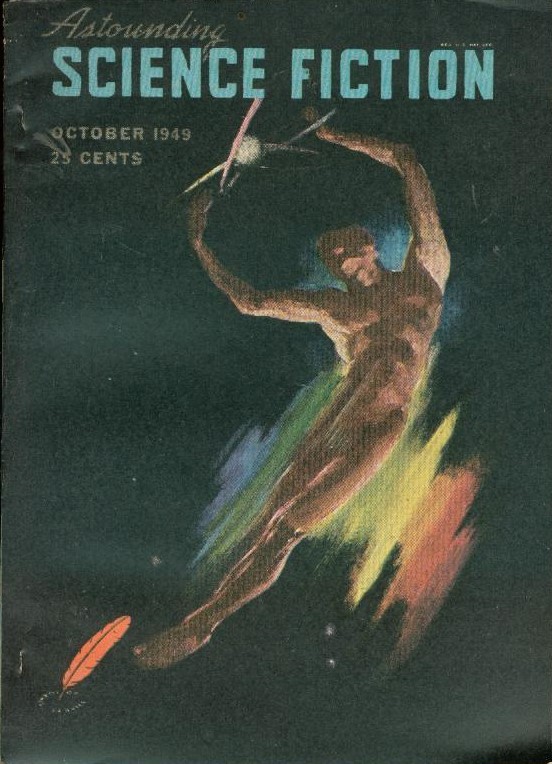

Alejandro de Cañedo’s cover for Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (October 1949)

3.75/5 (Good)

“The Aristocrat” first appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (October 1949). You can read it online here.

Unlike Chan Davis’ other two 40s tales of nuclear terror, “The Aristocrat” takes place in the post-war world. A few generations post-bomb, the survivors are bifurcated into two distinct groups: the Folk, visibly mutated yet tolerant of radiation, and the Elders, who retain “human” features yet are susceptible to radiation poisoning. The story follows the radiation-sick Elder Stevan, who never leaves the immediate vicinity of a Temple filled with the books and artifacts from the pre-war era. He uses soft power, the well of knowledge within the books at his disposal, and an informal spy network to keep a pulse on Folk community that supports him. He dolls out punishment. Charts and affirms marriages. And imagines discovering another Elder before his impending death. His informants bring word that an eighteen-year-old woman was captured on a raid (that didn’t have his sanction)–and she looks like him!

Elder Stevan (35) marries Barbi (18) and tells the folk to call her an Elder. He begins to teacher he how to read. And can’t help but notice that she keeps many of her personal views about how society should be tight to her chest. The little she shares reveals a hatred of Stevan’s perpetuation of nobility. His own views start to weaken: “the aristocrat had denied the slave education, and called him stupid; had given him routine jobs with no hope of advancement, and called him lazy; had refused him his share of civilization, and called him a savage. All without justification. Barbi was right” (22). And the threads tighten and conflict looms when she gives birth to a child that looks Folk. Stevan must unravel the genetic mystery before it is too lat. And Barbi weaves her own plans.

While still resisting simplistic answers, it’s hard not read “The Aristocrat” as influenced by Davis’ Communist political views as the future that emerges appears classless. Barbi’s actions remove the boundaries between the Folk and the Elders. The Elders will no longer profit off the labor of the Folk or define the paths their society might take. Stevan’s views of resurrecting the old world and maintaining his power over the Folk adhere to a pattern of historical cyclicality in which the elite profit off producers. Barbi’s actions not only redefine the relationships between survivors but sheer off the remaining institutional and intellectual anchors of the pre-War era. In this sense, “The Aristocrat” fits the authorial desire to “build, a new infinitely better world out of the old” [1]. Davis hints that future oppression still might occur as scholars will no longer be able to rule from their ivory towers.

“The Aristocrat” takes its time building the world and exploring ideas before conflict unfolds. For those who can tolerate a narrator who represents the evils of the past world and enjoy post-war stories of rebuilding society, “The Aristocrat” is well worth your time [2].

Notes

[1] See Martha Bartter’s article “Nuclear Holocaust as Urban Renewal” (1986), 148.

[2] For a brief discussion of Chan Davis’ views on his own short story, check out this worthwhile interview over at Strange Horizons.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

The only Davis I’ve read is “Letter to Ellen” which seems like it’s unlike the rest of his work.

What was it about?

It’s about a project to build an artificial biological human and the difficulty that the products of that effort have when they learn about their origin

Sounds intriguing! And it appears he demonstrated some range of vision in the handful of short stories he wrote.

The only Chan Davis story I know for sure I have read is ‘Adrift on the Policy Level’ (1959). I like it but no longer recall why! Maybe time for a re-visit.

A ‘communist’ you say. Do you know if he was a member of the CPUSA or another flavour of communism, say Trotskyist, para-Trotskyist, or what have you? So many flavours and fiefdoms. For instance, Mack Reynolds was no Stalinist, having been a member of the SLP. But members of the CPUSA in the 1940s and 50s were at the very least “soft” Stalinists (shudder).

I don’t know his exact band of Communism. Another reason I want to read the book I mentioned at the beginning of the review. But yes, I know that when he wrote these three stories, he had recently rejoined the Communist Party USA right after WWII (he apparently had left the party right before the war to attend Navy officer training). According to Wikipedia, he supported the Progressive Party Candidate Henry A. Wallace for President in 1948 (Wallace supported desegregation of public schools, racial and gender equality, a national health-insurance program, etc.) and left CPUSA in 1951.

I love the way SF in the 40s and 50s become a site of radical contestation, in part. And is seen in this way by radicals like Davis and others (Merril comes to mind too). SF as the new utopian fiction with a hefty dose of (capitalist… socialist) dystopia for good measure.

Let’s not forget the “Libertarian” Trotskyist Ward Moore!

How could I!

A monograph on SF and the many flavours of anarcho-communism sounds like a plan…

I’d read it!

And Howard Fast… tried to read his short stories at one point and did not get far, alas. Born on the same day as Mack Reynolds!

Do tell. Is there anything I can read on this subject? Moore has long seemed to me an interesting and slightly mysterious figure.

I brought it up and cited my sources in my review of Moore’s “Lot” https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2023/01/29/short-story-reviews-ward-moores-lot-1953-and-langdon-jones-i-remember-anita-1964/

The brief comments about his politics appeared in Mike Davis’ “Ward Moore’s Freedom Ride” in Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 38, No. 3 (November 2011), 386.

I’ve only read “The Nightmare,” in Conklin’s A Treasury of Science Fiction. It’s unexceptional, but given Davis would’ve been only 19 when he wrote it it could’ve been leagues worse! It’s one of those few debut stories to make the cover, but in this case I think it’s because Campbell thought it super-timely. Honestly William Timmins’s cover might be more memorable than the story.

I agree. Definitely why I stated that it’s only recommended for fans of the very first speculations post-Hiroshima. Historical context gave it value for me even if the story was definitely “meh.”