My series on 1950s stories on sex and sexuality finds itself relentlessly drawn back to the well-trodden post-apocalyptic wasteland. New moralities are inscribed and ritualized in the wreckage. As Paul Brians points out in Nuclear Holocaust: Atomic War in Fiction, 1895-1984 (1987), authors in the 1950s and 60s demonstrate an obsession with the sex in the post-holocaust landscape as if they are “feverishly battling atomic thanatos with eros” [note 1]. Here I have paired two moments that dance around either side of the nuclear nightmare. Langdon Jones’ “I Remember, Anita…” (1964), the most controversial story from the early issues of Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds, explores an intense love affair in the moments before and after impact. Ward Moore’s shocker “Lot” (1953) charts the moments after impact as the masses flee from the city.

Previously: Fritz Leiber’s “The Ship Sails at Midnight” (1950) and Theodore Sturgeon’s “The Sex Opposite” (1952)

Up next: Damon Knight’s “Not With a Bang” (1950)

If any stories on 1950s stories on sex and sexuality come to mind that I haven’t read yet let me know in the comments. I have a substantial list waiting to be covered but I suspect it’s far from comprehensive.

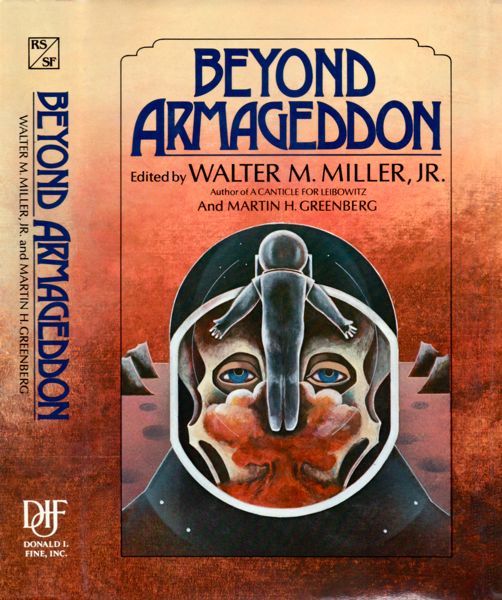

Loretta Trezzo’s cover for the 1st edition of Beyond Armageddon: Twenty-One Sermons to the Dead, ed. Martin H. Greenberg and Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1985)

4.5/5 (Very Good)

Ward Moore’s “Lot” first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas (May 1953). You can read it online here.

Ward Moore (1903-1978) strikes an unusual–and mostly unknown–figure. Born of Jewish parents, Moore supposedly was kicked out of high school in New York City for anti-war activity during WWI. He claimed to have spent years “tramping” around United States before managing a bookshop in Chicago. He interacted with the “Father of the Beats” Kenneth Rexroth (1905-1982), in whose work he appears as a mad bohemian, and later moved to California (his home for the rest of his life) where he received a Federal Writers Project job for the WPA [note 2]. Mike Davis, in “Ward Moore’s Freedom Ride”, describes him as a “whirling dervish of unorthodox opinion and radical sensibility, a Trotskyist and a libertarian whose avowed literary models were Rabelais, Jarry, and Grimmelshausen” [note 3]. He occasionally wrote science fiction—his most productive period was in the 1950s for F&SF—along with mainstream novels and book reviews. “Lot” (1953) and its sequel “Lot’s Daughter” (1954)–which I’ll review later in this series–are his best known short fictions.

“Lot” (1953) certainly contains the Rabelaisian touch! Moore reimagines the horrifying story of Lot in the aftermath of a nuclear war. In the biblical story, Lot–with his daughters and wife–flee the city of Sodom before its destruction by God. Lot’s wife looks backward and is turned into a pillar of salt [note 4]. As they have no men to marry while hiding out in a desert cave, Lot’s daughters conspire to bear children by their father. In Moore’s telling, Mr. Jimmon flees Malibu after a nuclear strike with his family–wife Molly, sons Jir and Wendell, and daughter Erika–in tow. He knew the end was coming and had prepared his station wagon accordingly and identified place away from the highways to create a new life. Molly and their sons cannot frame their flight as anything other than a temporary vacation. They beg for hotels and the luxuries of the past. Mr. Jimmon demands they abandon their family dog Waggie.

Mr. Jimmon, in his interior monologue, ridicules their inability to see how they must cast off their modern trappings and become their pioneer ancestors. Molly snips, “You’re just a little too old and flabby for pioneering. Even when you were younger you were hardly the rugged, outdoor type” (116). His hatred is not as strong for Erika, whom he sees as his only child and possessed with his own foresight and emotional strength. The others follow too closely to the template of their mother. While he drives out of the city, propelled by a rekindled purpose, Mr. Jimmon imagines what will become of his family. He see his wife disintegrating and dying rapidly in the wilderness (115). He speculates that the unintelligent Wendell would immediately forget how to read and turn into a savage (115). And Jir would join a youth gang and embrace violence before meeting his own premature end (115). He suspects Erika has the will and intelligence to survive. And so Mr. Jimmon hatches a plan…

As with Sherwood Springer’s “No Land of Nod” (1952), Moore attempts to tackle the morality of the post-apocalyptic sexual landscape. Unlike Springer’s narrator who wants to do well within a world presented as a possible future, Moore takes a distinctly satirical position that pummels and ridicules the middle-aged American father who yearns to make anew. The biblical model isn’t taken as some pattern of behavior that might reemerge in a transformed world. Instead, it’s presented as a delusional monologue of a hateful man who imagines he’s been graced with some special insight the ignorant masses lack. He doesn’t try to weld together his modern family into a unit that will survive the fall of the city. He abandons it at a gas station in order to make a new one with his daughter. Laced with sad and uncomfortable cruelty, “Lot” places the seemingly arbitrary terror (and power) of the Old Testament God in the mind of a sad American misogynist. A subversive and deliberately grotesque account of the fragmentation of the American family in a moment of crisis.

Ed Emswhiller’s cover for the 1960 edition of The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, Third Series, ed. Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas (1954)

Jack Coggins’ cover for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas (May 1953)

Jakubowicz’s cover for New Worlds, ed. Michael Moorcock (September-October 1964)

3.75/5 (Good)

Langdon Jones’ “I Remember, Anita…” first appeared in New Worlds, ed. Michael Moorcock (September-October 1964). You can read it online here.

Langdon Jones (1942-2021) is a lesser known luminary of the New Wave movement. He contributed a spectacular sequence of stories between 1964 and 1972, served as the assistant editor for Moorcock’s New Worlds starting in July 1967, and from April 1969 to July 1969 issues took over editorial responsibilities. Jones also edited an influential anthology, The New SF: An Original Anthology of Modern Speculative Fiction (1969), and was responsible for reconstructing Mervyn Peake’s Titus Alone (1959), that had been heavily edited due to Peake’s illness, for publication in the definitive 1970 edition [note 5]. I have reviewed his collection The Eye of the Lens (1972), and highlight “The Hall of Machines” (1968), “The Time Machine” (1969), and “The Great Clock” (1966) as representative of the New Wave at its best. I described his work, even the weakest stories, as demonstrating craft, a willingness to experiment, and an eye for the image.

Mike Ashley, in Transformations: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1950-1970 (2005), designates Jones one of the “less remembered New Worlds authors” and “I Remember, Anita…”, with its detailed depiction of sex and love, the most controversial story from the first issues of New Worlds under Moorcock’s tutelage [note 6]. While perhaps “taboo-breaking” at the time, the critical reaction to Jones’ story has not been kind. Ashley appears to agree with the letters New Worlds received that suggested that Jones “might be running before he could walk and that he shouldn’t be so pretentious” [note 7]. Colin Greenland in The Entropy Exhibition: Michael Moorcock and the British ‘New Wave’ in Science Fiction (1983) is even more dismissive of its literary qualities yet emphasizes how shocking it must have been to readers at the time [note 8]. While Jones does not reach the alluring heights of “The Hall of Machines” (1968), I can’t help but see “I Remember, Anita…” as a solid early story with a handful of redeeming qualities.

“I Remember, Anita…” is a simple story. Two hurt individuals–Mikey and Anita–fall in love while on vacation in the town of Aberfoyle, Scotland, surrounded by “the wild cragginess of the mountains round” (69). The mountains not only provide the metaphoric insulation from the trauma of their pasts necessary to kindle love but block out the world’s spiraling descent into war. The precocious 20-year-old Mikey, like Jones himself a student of music, finds himself at a professional and personal impasse. His way of interpreting the world through his music feels stuck in the past, outmoded. His personal life, mirroring the world around, descends into drink and suicidal despair. He wants to be “mothered” (73). Anita is twice Mikey’s age. She’s brilliant and seems ready achieve great things despite her rough childhood as an illegitimate child whose father died young. The men in her life take advantage of her. Those memories prevent her from finding someone she can trust. They both share their stories. They fall into fierce, obsessive, and passionate love. “Oh Anita,” Mikey recalls, “I remember our love-making! I remember the perfection of your body; the smoothness of your flesh. […] The black triangle, where I used to find the warmth of you” (76). But as the tempest of their lust and love courses through all elements of their existence, the end of it all looms on the horizon.

Jones’ story feels so different from the stories of the day. It’s erotic. It’s filled with passion–even if its not always the most adeptly drawn. It features an unusual couple who both find solace in each other’s arms. They need each other. It’s passion thrust against the brutal violence of Armageddon. It’s melodramatic to the extreme. Like Malzberg later in the 60s, Jones repurposes the language of erotic literature for rather more disturbing ends–revealing and entwining humanity’s destructive obsessions. I find the pairing of the distant macro (the Cold War crises) with the most intimate micro-moments (sex) an affective and effective choice. An original, if a bit unpolished, post-apocalyptic New Wave tale.

This story has rekindled my goal of reading the rest of Jones’ short stories that didn’t appear in The Eye of the Lens (1972). Somewhat recommended for fans of the New Wave movement and sex and sexuality in 1960s SF.

Notes

[1] You can read Brians’ book online. I found the monograph, despite its age, particularly useful due to the immense bibliography that takes up most of the volume — an indispensable resource. Here is the chapter I am citing. Brians is drawing on Albert I. Berger, “Love, Death and the Atomic Bomb: Sexuality and Community in Science Fiction, 1935-55,” Science-Fiction Studies 8 (1981).

[2] Ward Moore’s Wikipedia entry and SF Encyclopedia listing.

[3] Jones’ SF Encyclopedia entry.

[4] Mike Davis’ “Ward Moore’s Freedom Ride” in Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 38, No. 3 (November 2011), 386.

[5] There’s a disturbing list of rock pillars named after Lot’s wife! Scroll to the bottom to see the visual gallery.

[6] Ashley, 240.

[7] Ashley, 240.

[8] According to Greenland, “The style is atrocious, a mixture of protest poem, soft porn, and women’s magazine romance” (23). He points out that Jones himself “admits that ‘Anita’ is a bad story and wants nothing more to do with it. But in 1964, to the sf fans who found it lurking in their favorite magazine, it must have been quite a different experience” (24).

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

People were at one end of the extreme spectrum humanity tends to follow in these things, now, we are at the other extreme end. Keep writing! Definitely enjoying.

Thank you for stopping by. Tempted to read the stories? Have you read anything else by either author?

Old Mars, a work by George R.R. Martin with a portion by Michael M – personally I much preferred the Princess of Mars series by Burrough (obviously written pre 50s) and from the 50s, Asimov, Poul Anderson, and a one off that I have quite enjoyed by Andre Norton (Star Guard) I love scifi, and have quite enjoyed a new genre that utilizes the mmporg/lit approach that has been popping up rather frequently of late.

Like many I tend to see human expression or that expression being currently repressed in physical culture/social norms within the writings of others. Art does truly mirror the thoughts and desires of the creators of it.

Again, love your writing and break downs especially.

Thank you for the kind words. I was asking though if you had read anything by the authors I just wrote about — Ward Moore and Langdon Jones. Moore is best known for his alternative history novel Bring the Jubilee (1953) in which the Confederacy wins the Civil War.

As for George R. R. Martin, I’ve read a few of his older SF short stories here and there (for example some from his collection Songs of Stars and Shadows) and have tracked down some of his early novels like Dying of the Light (1977) but haven’t got to them yet. I have reviewed tons of Anderson on the site but can’t firmly say he’s an author for me as I age. Burroughs and Norton were authors I read as an older teen but no longer appeal.

I don’t completely understand your comment about “a new genre that utilizes the mmporg/lit approach that has been popping up rather frequently of late.”

My apologies, I misunderstood and yes, I have read Bring the Jubilee, it is not horrible – 😊 my apologies for misunderstanding:(

No worries! I was just curious if you knew of any other works by both that I should track down. I own a copy of Bring the Jubilee but haven’t read it yet.

It’s solid! And sadly no, I read quite a bit and still look around and realize, I wish I had 48 hrs in a day and more reading time – 🙃

I’ve never read the dying of the light –

If you get to it before me, let me know what you think!

Here’s my purchase post which generated some conversation about the book: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2019/06/08/updates-recent-science-fiction-acquisitions-no-ccxii-martin-jeter-lee-gerrold/

Absolutely love that list and your library!

So beautiful!

This is the first time I’ve read anything by Langdon Jones. I’ll admit he’s a good prose stylist, it really draws you in, as does Ballard with his quite different, cold, detached manner of writing. I can see that at the time that it was written, it would have been considered quite daring, but obviously it was meant to be. The editor[s] of “New Worlds” wanted controversial material to line the seams of their publication.

If you’re willing to further explore Jones’ work, make sure to track down the stories in his collection The Eye of the Lens (1972) (you can borrow it on Internet Archive). I’d argue that “The Hall of Machines” (1968) is a true New Wave masterpiece. It tightens up the prose (although what it’s describing is truly immense and alien in every way possible) and sends you on a Borgesian exploration of a bizarre instillation. It also appeared in Merril’s influential anthology England Swings SF (1968).

Here’s a link to its original New Worlds publication issue: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gK71lUEVDCKq6yky17G4OQ65Peq3uPGG/view

I read the three short stories in the link you provided me. I’m pleased to have discovered his SF. I can see the Borges influence. I liked “The Eye of the Lens” the most, which was also comical.

Yeah, all three are sort of linked together. I find “The Hall of Machines” portion the best.

Glad you enjoyed it!

I was disturbed for several days after reading “I Remember, Anita…” a few years ago. It wasn’t what I expected, especially for something released in the mid-60s. I’ve been meaning to finish The Eye of The Lens collection, so you’ve motivated me to get back to it. It was a shame that Jones never wrote a novel, especially with how long he lived.

Yeah, it’s a heavy hitter. Let me know any other favorites from The Eye of the Lens collection. I listened to a podcast interview at one point that explained why he quit SF. The podcast also included his unpublished short story (that was to appear in The Last Dangerous Visions). https://play.acast.com/s/starshipsofa/aural-delights-no-146-langdon-jones

Fantastic! Thanks for the link.

No problem. Let me know if you learned anything interesting — it’s been quite a while since I listened to the episode.

Your take on “Lot” has almost convinced that it is a good story! Perhaps I was too overwhelmed by the misanthropic viewpoint of Mr Jimmon—which is the point after. A horrid character who one hopes gets his comeuppance at the hands of his daughter, with any luck.

Still, now that I know Moore is a fellow veteran of the far-left, I feel a need to seek out his other work. I’ll have a look out for the sequel, and perhaps reread ‘The Fellow Who Married the Maxill Girl’ (which I barely recall) along the way.

I haven’t read the Langdon Jones but will keep an eye out for it. I have a copy of his edited collection of New Wave stories, ‘The New SF’, and am pretty keen to read that. Interestingly, and unlike many of his self-aggrandizing contemporaries, Jones doesn’t include one of his own stories in the collection.

Have you found a certain disgust mixed with prurience when it comes to comments on SF that attempt to deal with sex? Or is this just a result of some of the stupid crap that I’ve so far read online? It would be interesting to track the changing representations and reception of sex in SF through the 1960s, simply because you go from a relatively buttoned-down attitude at the beginning of the decade, to a no holds barred reality at the end. Silverberg, again, is a good measure of this. I admit I find the result in his work somewhat mixed—for instance, I recently put down his novel ‘Up the Line’ because of the decent into temporal incest, which I found boring more than anything else.

I’m currently reading Spinrad’s ‘Bug Jack Barron’, and whereas I find some of his sub-Beat prose of interest (though often bordering on the irritating), his representations of sex is very late-60s-sexual-revolution-male-desire-writ-large, and not in a good way (though he does seem to be occasionally aware of this).

Sorry for the delayed response. Yeah, I can imagine that this would bounce off a lot of people. The story is repulsive in its implications and telling and characters. The interior monologue of Mr. Jimmon is what makes the story so horrifying in my view — and subversive. I don’t think there could be a more uncomfortable takedown of the American family and delusions of survival. The entire time you get the sense that there would be some serious “we will survive this evil Communist attack” but instead, the small anti-Communist moments are presented as Jir’s childish fantasies of violence. And considering all the stories I’ve been reading about Biblical narratives recast in the future, this feels a bit more like Disch than Sherwood Spinger.

Are you referencing popular views voiced in letters sent into the magazines of the day? I think “Lot” came in third in the poll for best stories of that issue (I’ll have to investigate). And responses to Farmer’s “The Lovers” (1952) were overwhelmingly positive (I charted those in my post) despite a handful of contrary views.

No worries about the delay, after all I am the master of the delayed response!

You’re right that it is a grim revelation of the heart of the nuclear family. It calls to mind the words of a writer I am not a great fan of, Foucault, who once remarked that the bourgeois family is an inducement to incest (or words to that effect).

My reference is fairly anecdotal: the comments left by some people on review sites, opining about the confronting sexual content of various stories.

Both William Tenn stories I recently reviewed might be your cup of tea — especially “Eastward Ho!” (1958).

And “Generation of Noah” (1951) might be read VERY productively in conjunction with Ward Moore’s “Lot” (1953).