Today I’ve selected two early Clifford D. Simak “apprentice” stories–“Masquerade” (1941) and “Tools” (1942)–deeply critical of the American business ethic.1 Collectively they posit a future in which colonization goes hand-in-hand with the exploitation of resources, workers, and threatens the alien intelligences they encounter.2

Welcome to a future of capitalistic vastation!

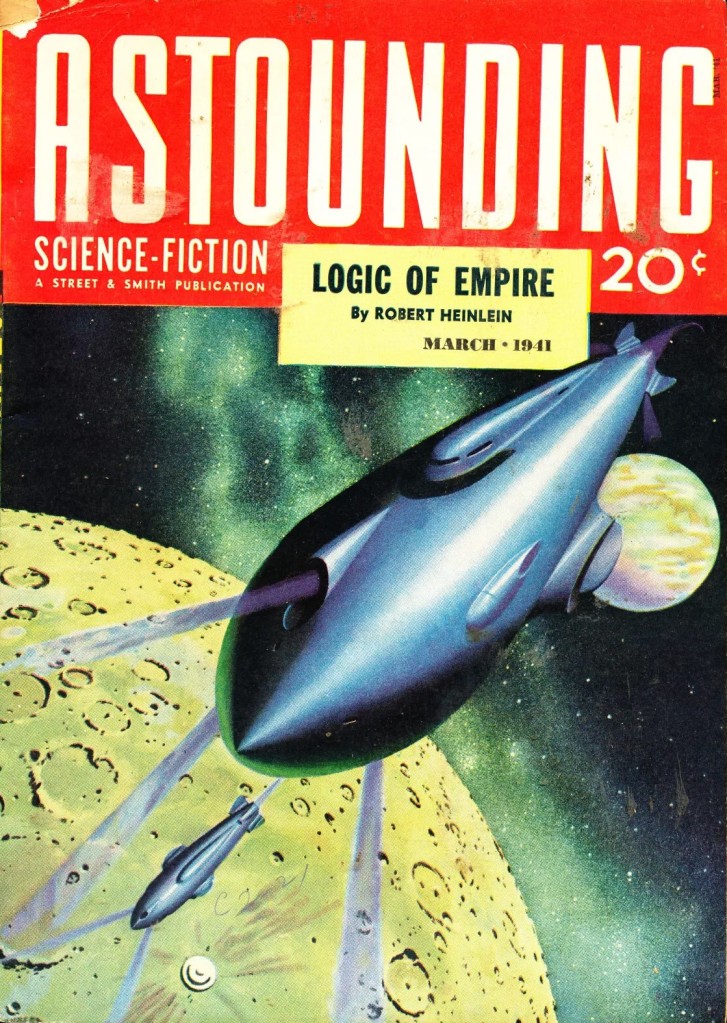

Hubert Rodger’s cover for Astounding, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (March 1941)

3/5 (Average)

“Masquerade” first appeared in Astounding, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (March 1941). You can read it online here.

In the surprisingly bleak “Masquerade” (1941), metamorphic aliens on Mercury’s radiation-blasted surface parrot human actions. Beneath their clownish behavior is a plot, a plot to takedown an Earth corporation. The story begins with a disquieting sequence in the bleak expanse outside a sunlight harvesting power station on the surface of Mercury: “the Roman candles, snatching their shapes from Creepy’s mind, had assumed the form of Terrestrial hillbillies and were cavorting the measures of a square dance” (57). The Candles, “kicking up the dust, shuffling and hopping and flapping their arms” (58), are the mysterious natives of Mercury. In classic Simak fashion, there’s a method to their apparent comic madness.3

Captain Craig, responsible for guiding the sun’s power from the surface in a “spaceward beam” (61), holds an enlightened view of the alien Other. He defends the strange distant behavior of the Candles, and their connection to the place: “they were here when men came, and they’ll probably be here long after men depart” (59). Perhaps they refuse to communicate with humans (and explain their rituals) “because they regard Man as an inferior race–a race upon which it isn’t even worth their while to waste their time” (60). Page, on the other hand, believes the absence of cities, machines, and “civilizations” demonstrates a lack of intelligence (60). He seeks to abduct some of the Candles for a money-making circus venture on Earth. The glimpses of Earth the story provides hint at a Earth society characterized by bribes, boot-licking, and industrial and urban expansion (i.e. “bulldozing”) (61). Page represents that world. Craig, amongst the aliens, comes to a different set of conclusions. But what happens if there’s a crisis that threatens the status quo?

Despite Craig’s accepting view of the Candles, a series of events in which the aliens infiltrate the power station appears to affirm the inability to live in harmony. Humanity’s desire for cheap energy trumps all else, even if their presence radically alters an alien culture. Craig sends a report back to earth defending the use of violence in self-defense if the Candles interrupt the export of power: “anything that would swiftly deprive them of energy would serve” (74). It is stated that humans waged genocide against other species on other planets. A position that Craig, at least, does not support (74). Craig concludes that humans must develop a new source of “universal power” in case the Candles successfully strike (74). Humanity’s greed marches on. Even the enlightened turn towards thoughts of violence.

“Masquerade” is clearly an early, and unpolished, story. Despite a few moments of beauty (the opening line describing the unusual alien behaviors on the bleak surface of Mercury), Simak resorts to jarring dialogue tags. If you show me a pattern (good or bad), my mind will obsessively catalogue and document. Characters rarely “said” anything to each other. Instead, they yelled, agreed, roared, suggested, yelped, moaned, growled, countered, and snapped. Use in moderation! Pulpy prose hiccups aside, “Masquerade” contains an incubatory version of Simak’s critique of modern “business ethic” and unusual aliens that serve to illustrate humanity’s foibles and destructive tendencies.

Recommended only for fans of Simak or those interested in critical takes on the sinister ramifications of future capitalism.

Eron’s interior art for “Masquerade” in Astounding (March 1941)

Frank Kramer’s interior art for “Tools” in Astounding (July 1942)

3.5/5 (Good)

“Tools” first appeared in Astounding, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (July 1942). You can read it online here.

In “Tools” (1942), the unchecked capitalist vastation shifts from Mercury to Venus and a new form of power. Instead of harvesting the sun’s rays as in “Masquerade,” the monopoly Radium, Inc.—which “owns the Solar System, body and soul” (122)–exports shiploads of radium from the Venusian mines harvested by specialized robots “operating with ‘radon brains'” (120).

The story initially follows Harvey Boone, the official observe for the Solar Institute, who sends back reports to Earth on Archie, an unusual Venusian entity that lives within radon gas. Discovered and studied by Masterson, Archie communicates via the “radon” that (somehow) recognizes impulses “as intelligent symbols” and can manipulate the jar’s controls to produce a voice (120). Various characters interact with Archie, trapped in his prison. The company doctor, and Simak mouthpiece, is Archie’s favorite conversation partner. Archie refuses to share more information than he has to. And Boone’s fraying nerves, “any alien planet is hard to live on and stay sane” (119), presents an opportunity for Archie to escape. Free from the jar, Archie’s accumulated knowledge spreads across the planet, infecting the ‘radon brains’ of the robotic miners. Rebellion is literally in the air.

In comparison to the earlier “Masquerade,” “Tools” more explicitly delves into the impact of Radium, Inc.’s political, economic, and social domination. A brutal dystopia emerges. The manic company director, R. C. Webster, takes on the role of a sinister villain at the center of a vast network of secret police and spires (122). Countries jump when Webster snaps his fingers (122). School children learn “enthusiasm” about big business in school (125). The business elite are the new nobility, power passes from father to son. Life under the thrall of Webster and his cronies is the price “the people of Earth had to pay for solar expansion, for a solar empire” (122). And what a brutal price… It’s treason to suggest a different future free from Radium, Inc.’s embrace (125). Streeter, Webster’s mercenary strong man, shows no qualms replacing the robots with slave labor if Radium exports fall below acceptable levels (126). His police erect sentry towers to oversee the operation, guns ready in case of a worker revolt (126).

“Tools” reads as stridently anti-capitalist. Simak argues that the actual experience of worker oppression leads all to the same conclusion: Radium, Inc. must be overthrown. One cannot miss the Marxist notion of class consciousness that permeates the pages. Garrison, the leader of the mine, provides the best example: “Call it treason […] Call it anything you like. It’s the language that’s being talked up and down the System. Wherever men work out their hearts and strange their conscience in hope of scraps from Radium, Inc.’s table, they’re saying the same thing we are saying” (125). When Webster proposes sending men to replace the machines, he protests: “They’ll revolt” (126). Archie’s actions, however brutal, offer a glimmer of possibility.

Recommended for fans of Simak.

Charles de Feo’s cover for Astounding, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (July 1942)

- I snagged the phrase “business ethic” from Thomas D. Clareson’s article “Clifford D. Simak: The Inhabited Universe” in Voices for the Future: Essays on Major Science Fiction (1976), 79. He uses the term to describe Simak’s story “Shotgun Cure” (1961), in which a doctor struggles with whether or not to release an alien vaccine that will cure all illness, and, in so doing, put him out of work. Clareson also adds Ring Around the Sun (1953) as another work that satirizes “business ethic”; M. Keith Booker discusses Ring Around the Sun in Monsters, Mushroom Clouds, and the Cold War (2001), 55-59 as his example of Simak’s capitalist critique: “his work provides critiques of capitalism that sometimes sound almost Marxist, but are also some of the clearest science fiction explorations of a nostalgic longing for the pre-capitalist past that informed much conservative though in the decade, including that of the New Critics” (55); For a nuanced look at Simak’s often complex notion of the “pre-capitalist past” see Christopher Cokinos’ “The Pastoral Complexities of Clifford Simak: The Land Ethic and Pulp Lyricism in Time and Again” in Extrapolation, vol. 55. no. 2 (2014),133-152. ↩︎

- Robert J. Ewald, in When the Fires Burn High and the Wind is From the North: The Pastoral Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak (2006), lists the following classic Simak themes as present amongst his earliest “apprentice” stories: “the criticism of human society for its failure to use the gifts of technology for its own improvement, the greed of large corporations who use technology to expand their corporate empires into the Solar System and to the stars, the community of intelligent races who sit in judgement of human actions, and the prospects of the evolution of the human race into a worthy member of this galactic brotherhood” (37). Other early stories Ewald highlights as particularly critical of capitalism include Empire (1951) [In 1939, Campbell, Jr. gave Simak his own manuscript from the 1920s to rewrite. Simak, albeit with deep suspicion, complied but Campbell didn’t run it in Astounding. H. L. Gold published it in 1951], “Carbon Copy” (1957), “Spaceship in a Flask” (1941), and “Lobby” (1944). ↩︎

- For Simak’s treatment of the alien, check out William Lomax’s “The ‘Invisible Alien’ in the Science Fiction of Clifford Simak” in Extrapolation, vol. 30, no. 2 (1989), 133-145. The alien in Simak’s stories often serve to show how truly alien humans really are: “[humanity’s] vast economic and property systems are outlandish traps. He deifies money and constantly bickers for advantage; commercialism is rampant, and industry produces junk.” (135) ↩︎

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Simak was ever a one to criticize the shortcomings and built-in faults of mankind.

Have any favorite Simak stories? These were solid early works — but nothing spectacular… I read City and The Way Station (among a few others novels) as an older teen. I am currently reading another one of his anti-capitalist novels.

I’ve mainly read his short stories and have no favorites among these. I have an overall view of him but nothing in particular. I can’t get really enthused about his writings as they tend too much toward the pessimistic.

His futures aren’t without hope. We might have to rely on aliens to show us the path, but there’s still hope… That said, one of the reasons I adore the 50s (I know these are earlier) is the serious pessimistic strain of satire. There are so few utopias in the 50s. Thank goodness. And of course, that morphs into fascinating new forms with the New Wave in the following decade.

As my old blog friend Megan AM (who unfortunately deleted her wonderful site) once said, Joachim Boaz likes his SF ” “moody, broody, meta, and twisted.” So yeah, I’m going to feature a lot of that vibe!

Science fiction usually has problems to it; I like those to be resolved and not leave any problems behind. A person just sits and stares at something like NINETEEN EIGHTY FOUR. This leaves depression in the reader. This isn’t so with Simak’s stories, but one is left with a feeling that things aren’t going to be right. The way things are getting, Simak seems to be right with it, which leaves the reader king of caught. But I understand liking a lot of complexity in a story.

I enjoyed all four of the stories in his collection The Marathon Photograph; two are from 1974 & the other two from 1980.

I re-read his 1953 novel Ring Around the Sun not that long ago and was struck by similarities with his much later The Visitors (1980) and the outside undermining of capitalism.

My usual Flickr comments

Marathon – https://www.flickr.com/photos/17270214@N05/6263925150

Ring – https://www.flickr.com/photos/17270214@N05/49852029501

I plan on reading Ring Around the Sun for this project. Thanks for the links.

Simak was always one of my go-to authours while growing up. “Destiny Doll”, “The Goblin Reservation”, “The Werewolf Principle”, “City”, “Cemetery World”, etc. It wasn’t until later that I realized that a lot of his fiction had a strong undercurrant of cynicism. Witness his novel “Our Children’s Children”. Maybe it was a result of his years as a newspaperman.

I enjoyed quite a few of his works as an older teen as well — City, Cemetery World (although, I’m not sure I loved that one at the time), The Way Station, etc. I actually read The Werewolf Principle relatively recently — there’s a review on the site. Why Call Them Back from Heaven? remains one of my favorite Simak novels.

But yes, I enjoy his cynicism. And I think there is quite a bit of philosophical and social commentary behind the disarming rural locales and characters.

Have only read City, Why Call Them Back From Heaven, and a handful of short stories but have enjoyed the peculiar idiosyncrasies of all of them. Need to explore further, obviously. Never really considered his politica before (beyond the a kind of conservative agrarian nostalgia evidenced in what I’ve read so far); the labor angle is interesting.

I am fascinated with his “agrarian nostalgia” — I am not sure it’s conservative though (certainly a debated point in the limited scholarship on Simak!). He grew up in a super rural part of Wisconsin (the town in which most of his stories take place) and headed to Minneapolis, Minnesota to find work (newspaper man his entire life). He rode a horse to high school. He constructed, like I have for my childhood home in rural Appalachian Virginia that I think about often and pine for (in a perhaps misguided way), versions of his childhood home in so many of his stories. Is it conservative? His futures, for example the one in “Full Cycle” that I covered relatively recently, posits an entire breakdown of capitalism and the recreation of something new — that’s communal, migratory, etc. I find him hard to pigeonhole into an easy dichotomy. I also wonder how influenced he was by the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party (that merged with Democratic party post-WWII), a leftist political group that emphasized farmer-based labor unions that was closely allied with the New Deal policies of Roosevelt. It was a third party force in the state in the 30s that often won political office. It had a rural focus. And, as he was a newspaper reporter, he would be intimately aware of the local political world in which he lived and worked.

That’s when the banksters focused hard on mechanizing/collectivising (into private not state hands) as much of agriculture as possible and using slave labor for the rest. We call ’em migrants but the difference is imperceptible. It’s worked a treat, hasn’t it?

Are you referring to the backlash to the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party? As Simak was born in 1904, he would have been utterly aware of the heyday of the party in the mid-1930s! Especially as a newspaper man.

That’s one specific example of the general trend I’m observing about, yes…and Simak would’ve been acutely aware of the issue in the Motherland of General Mills! There’s a documentary you might like called FLOUR POWER about how Post and General Mills took over Mpls…It’s on YouTube over on the Twin Cities PBS channel’s site.

Thank you! I don’t think ANY of the scholarship I have read (I have read everything I’ve been able to track down on Simak and his background) touches upon the possible connection between the politics of the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party and Simak…

The link for anyone curious: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8zlDoquXww&ab_channel=TwinCitiesPBS