For a large portion of the year, I’ve been collecting evidence on unions in post-WWII to very early 60s American science fiction.1 To be clear, I am not on the hunt for the best by these authors. This project is about stories that reference unions. I will read all the stories I can by American SF authors on the topic during this timeframe for this project in order to understand how authors responded to the historical moment in which they lived. Exciting!

A Bit of Historical Context

During the Great Depression, there was broad consensus among leftist thinkers that the labor movement would lead to radical change. The Second World War and the economic recovery shattered that consensus.2 The unions themselves underwent substantial transformation in this period. American corporate powers and their conservative congressional allies unleashed a “propaganda campaign” against the labor movement.3 This culminated in the contentious passage of the Taft-Hartley Act (1947), which weakened the ability of unions to strike. Over the course of the 1950s, automobile manufacturers and their unions pioneered a new relationship—adopted by other industries—in which companies agreed to grant wage increases, health care, and retirement plans in return for union support of long-term contracts. Increasingly, the political and social transformation of capitalism became secondary to preserving their organizations and maintaining a harmonious relationship with industry.4

Before World World II, anti-capitalist intellectuals imagined the labor movement as the American Proletariat which would, at any moment, transform the capitalist system. After WWII, they struggled to grapple with an economic system they had expected to collapse and the lack of interest in socialism within American unions.5 C. Wright Mills (1916-1962) argued labor had been co-opted by state power.6 Those that continued to support elements of the labor movement, such as Sidney Lens (1912-1986), struggled to rationalize labor’s part in the militarization of Cold War America.7 The one-time Trotskyist, Seymour Martin Lipset (1922-2006), argued that while the labor-movement fell short of representing the “class-based aims of a unified working class” it continued to play a roll in “prohibiting antidemocratic mass movements” by offering workers a role in a “mediating institution.”8 Most involved in the 60s New Left abandoned labor completely as a force for change and grouped unions as part of the liberal establishment, irrelevant in the construction of a new radicalism.9 As in, trade unions “focused on material gains, not fundamental social change.”10

Science fiction written in the post-WWII world likewise reflected outright criticism, deep ambivalence, and confusion over the role of the labor movement. Philip K. Dick’s “Stand-By” (1963) satirizes unions and the media in a post-scarcity world but tentatively suggests conflict between both might lead to the overthrow of a ruling computer and the eventual reemergence of democracy. Milton Lesser’s “Do It Yourself” (1957), one of only a handful unabashedly positive accounts on unions in the 50s, imagines a post-apocalyptic future in which the American individualist ethos reigns supreme. While banned and publicly ridiculed, a union secretly sends out agents to facilitate the rebuilding project. And in H. Beam Piper and John J. McGuire’s “Hunter Patrol” (1959), a ragtag group of disaffected, including a union man (an object of jest), attempt to recruit a soldier from earlier in time to overthrow a dictator. More than a few 50s authors, like Robert Silverberg (whom I’ll feature in a later post) and Clifford D. Simak, read and engaged with contemporary writers on the labor movement.11

Let’s get to the stories!

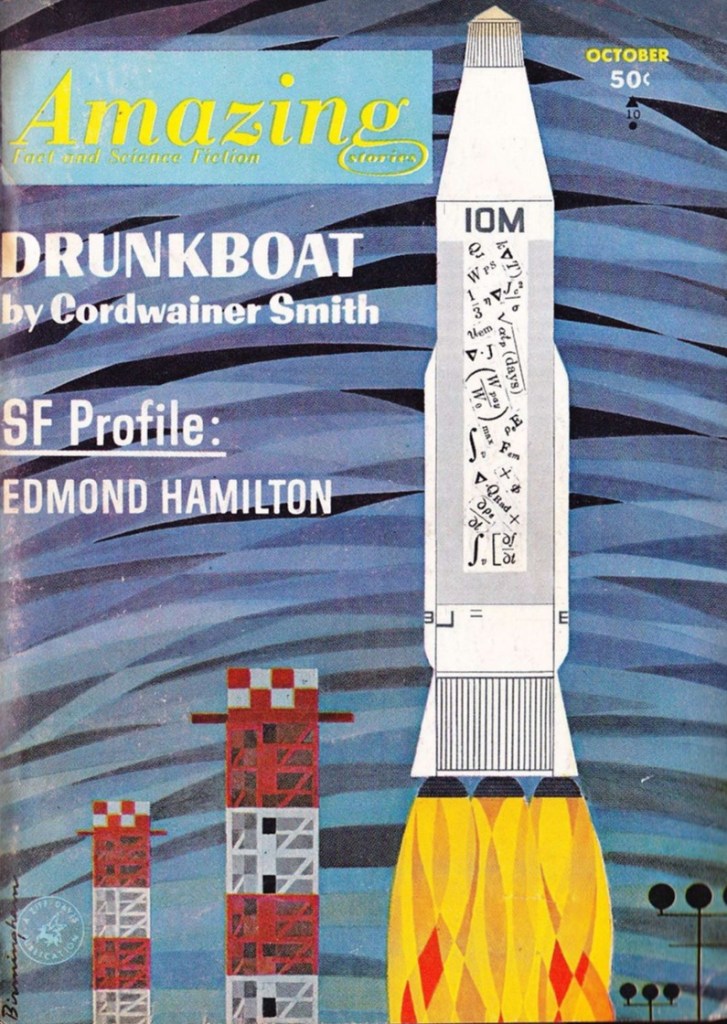

Lloyd Birmingham’s cover art for Amazing, ed. Cele Goldsmith (October 1963)

2.75/5 (Bad)

Philip K. Dick’s “Stand-By” first appeared in Amazing Stories, ed. Cele Goldsmith (October 1963). You can read it online here.

Unicephalon 40-D, a vast computer, rules humanity. As it calls citizens “comrades,” I assume Dick intends the computer to be read as a manifestation of totalitarian Communism. The computer’s stand-by human president in case it goes offline, Old Gus Schatz, dies. The Government Civil Servants’ Union appoints Max Fischer to take over. Obese with a weak heart, dependent on union funds, glued to his TV set, and without much independent thought, Max attempts to resist the appointment. The union assures him that it’ll be a dull task and an opportunity to take on whatever time-wasting hobby he so desires. Anyway, he doesn’t have a choice. The previous stand-in collected old car magazines (a reference to the glory days of industrial unionism) and the man before him made a massive rubber band ball now housed in the Smithsonian.

Unfortunately for Max there’s an alien invasion that knocks out Unicephalon 40-D. And Max, unelected, must take on the presidency. In predictable fashion, he immediately dismisses his cabinet and advisors, appoints his relatives to positions of power, and acts like a dictator. Only the actions of a news clown (he wears a red wig) named Jim-Jam Briskin, attempts to challenge his authority.

As with Simak’s “Worlds Without End” (1956), “Stand-By” presents unions as a victorious interest group in a larger, dystopian, political game after the fall of democracy. Both works extrapolate from the anti-union sentiment that grew over the course of the 50s. Mainstream news promoted the 1955 merger of the AFL (American Federation of Labor) and CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) as a “danger to the public.”12 Despite labor’s willingness to work within the existing political system in alliance with the Democrats, business leaders and Republican politicians feared the emergence of a monolithic union. During President Eisenhower’s administration, the McClellan Committee, in a series of sensational televised hearings between 1957 and 1960, heightened the public’s concern with corruption and “antidemocratic” practices in organized labor.13 Dick presents Max as the corrupt do-nothing union man who rose from poverty and pretends to have class.

While it’s not entirely clear how the future unfolds in Dick’s vision, it appears the Government Civil Servants’ Union attempted to maintain their influence with a strike after the ascent of Unicephalon 40-D. PKD not only levels a critique at the union man who no longer even needs to work yet collects a check but also the entire system in which everyone seems perfectly okay with a mechanical dictator. The jumbled designators of time-past, “presidency,” “elections,” “car magazines,” etc. all suggest the misguided motives of the labor movement who went along with Unicephalon’s takeover. Dick’s message is clear: unions promote the least worthy individuals and are inherently anti-democratic.

As a story, “Stand-By” is far from Philip K. Dick’s best. It doesn’t have any interesting surreal images, fascinating twists, or memorable turns of phrase. That said, I haven’t read the two sequels–“What’ll We Do with Ragland Park?” (1963) and “Cantata 140” (1963). “Cantata 140” forms the first part of Dick’s The Crack in Space (1964), which I’m almost positive I read before I started my website.

Avoid “Stand-By” unless you’re interested in organized labor in science fiction (me!) or a PKD completist.

George Schelling’s interior art for Philip K. Dick’s “Stand-By” in Amazing Stories, ed. Cele Goldsmith (October 1963)

Ed Emshwiller’s cover for Science Fiction Quarterly, ed. Robert W. Lowndes (November 1957)

3.5/5 (Good)

Milton Lesser’s “Do It Yourself” first appeared in Science Fiction Quarterly, ed. Robert W. Lowndes (November 1957). You can read it online here.

In a post-apocalyptical future, Long Island City (across from Manhattan) is a wasteland. In the “dregs of the old industrial society,” scavengers “who hadn’t yet been absorbed by the new rural America” attempt to live a fragment of the pre-bomb life (96). In the wreckage of the old U.N. building, now “the East Manhattan Home Workshop center” (96), a union prints DIY plans and sends out agents to assist those trying to make it on their own. Farther out on Long Island, rural farmers attempt to create a new life. However, behind the facade of DIY projects, workshops, and farmers, they still rely on scavenging. The catch? They can’t let their neighbors know. It must look like everyone is self-sufficient! McPeek is one of the union agents and the story follows his interaction with the Crawford farm. The patriarch of the family proclaims “I’ve got some farm now […] Maybe in the spring I’ll even find the time to plant some crops” (101). While the patriarch makes his plans, McPeek actually gets to work making a latrine, constructing a barn for livestock, making storm windows, fixing tractors, and getting the farm ready for planting. He must avoid vigilantes who raid the countryside attempting to root out anything that might symbolize the old order.

Lesser’s “Do It Yourself” works on multiple levels: 1) the unintended consequences of the Cold War rhetoric of American individualism vs. collective action. 2) A more specific satire of the explosion of the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) craze in the 1950s. and 3) A pointed acknowledgement of the value of unions in a moment in which there was growing anti-union sentiment (see the Dick review for more details).

The DIY craze reached a “fever pitch” in the 1950s with traveling road shows and conventions, handyman magazines, and front-cover stories in Time Magazine.14 SF often took this craze to humorous extremes, for example Clifford D. Simak’s robot strike in “How-2” (1954) comes to mind. The implications of Lesser’s take are far more disturbing. Lesser extrapolates that a WWIII leads to a economic depression in which the isolated and depressed attempted to do things for themselves. They interpreted “capital and industry” as artificial contrivances to “keep a man in debt” (102). Thus unions, now banned, secretly attempt to appeal to this individualistic ethos to get people creating new things again (instead of scavenging) on farms instead of factories (102). Unfortunately, the average person is more likely to make grandiose plans than implement them. Lesser argues that America’s fixation on individualism means that even in the post-apocalyptic wasteland, meaningful attempts to assist and mobilize workers will be met with outright violence. The union of idealist handymen, even banned, will continue to fight for tangible benefits for the next generation.

An odd and strangely intriguing post-apocalyptic rumination… This is the first Lesser story I’ve read. Somewhat recommended.

Ed Valigursky’s cover for Amazing Science Fiction Stories, ed. Cele Goldsmith (May 1959)

2/5 (Bad)

H. Beam Piper and John J. McGuire’s “Hunter Patrol” first appeared in Amazing Science Fiction Stories, ed. Cele Goldsmith (May 1959). You can read it online here.

A SF time-travel centric thriller with a few moments of debate over politics, “Hunter Patrol” plunges the reader into the media res. The story follows the soldier Benson on a raid, his last patrol until rotation home, deep into Pan-Soviet territory (the Cold War rages hot). He’s yanked from his time 50 years into the future by a strange group of disaffected plotting to overthrow a dictator. It appears that Cold War exhausted all sides (“the Soviet Bloc was broken up”) and left large portion of the US a nuclear wasteland, and St. Louis, now the location of the U.N., emerges as the World Capitol (25). The Guide rules the U.N. as a dictatorship. Through brainwashing, The Guide prevents his citizens from practicing violence (diabolical eugenics related executions excluded). Thus Benson, free of brainwashing and always up for a fight, is recruited to assassinate The Guide. There’s a catch, previous soldiers yanked from the past have all failed. And the nature of their failure isn’t entirely clear. As the narrative shifts dramatically from time to time a far more bizarre picture of sinister future technology and soda drinks (yes!) emerges.15 You know, time travel makes everything a paradox…. And everyone LOVES soda.

Where are the unions? H. Beam Piper (1904-1964) frequently featured unions in his stories, often with a very negative eye.16 I’ll write a post about his visions in the future. In “Hunter Patrol,” they are a tertiary concern in a wider satire of Cold War interventionalism and American commercialism. The rebels deliberately represent a variety of contemporary political and moral views–collectively they all desire to overthrow The Guide. One, Carl, is a member of a large “Union of all unions. Every working man in North America, Europe, Australia and South Africa belongs to it” (27). There’s a problem, “The Guide has us all hog-tied” and won’t let them strike preventing “closed-shop contracts to stick” and pay raises (27).17 Carl’s view, as with others in the story, is played for laughs as he clearly is not a poor worker. In another instance, Carl appears to adhere to a Marxist interpretation of class-struggle in his depiction of the fragmentation of the Soviet Bloc. His view is dismissed by Anthony, “capitalistic dictatorships he means […], let’s not confuse this with any class-struggle stuff” (25).

Regardless of the ambivalence towards organized labor, Piper and McGuire are overtly critical of big business and the sinister methods (brainwashing, chemicals, et.) it might use to acquire profit. As I’ve mentioned in other reviews, during the early Cold War Americans depicted Communism as denying inherent human freedoms of choice and enslaving the mind. After the Korean War, the terror of Communist brainwashing collided with fears of the detrimental effects of consumer culture and advertising. Perhaps Americans were also susceptible to commercial brainwashing deployed to convince the American family to conform and buy the latest products and models. “Hunter Patrol” is the perfect example of this paranoid lens turning inward.18

I am firmly aware that this is probably one of the worst H. Beam Piper short stories I could have picked up. That’s okay. I’m gathering evidence. If it’s from the 50s or early 60s and talks about unions I’ll read it!

Not recommended unless you’re an H. Beam Piper completist.

Notes

- I’ve gathered the titles of all the SF stories I’ve identified about unions and organized labor in footnote 1 here. ↩︎

- Jeffrey W. Coker’s Confronting American Labor: The New Left Dilemma (2002), 51. ↩︎

- See Elizabeth A. Fones-Wolf’s Selling Free Enterprise: The Business Assault on Labor and Liberalism, 1945-1960 (1994). She describes both a local and a national campaign. ↩︎

- I adapted this paragraph from my recent article “’We Must Start Over Again and Find Some Other Way of Life’: The Role of Organized Labor in the 1940s and ’50s Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak.” You can read the entire article here. The summary comes from Ch. 19, “Retrenchment, Cold War, and Consolidation, 1946-1955,” of Melvyn Dubofsky and Joseph A. McCartin’s Labor in America: A History, 9th edition (2017), 303-320 ↩︎

- Coker, 187; See also local level attempts to instill anti-union “American” values in Fones-Wolf’s Selling Free Enterprise; also, Melvyn Dubofsky and Joseph A. McCartin describe in Ch. 19 the alliance between the Democratic party and labor and the resulting purge of labor’s radical left wing. ↩︎

- Coker discusses C. Wright Mills in Ch. 3 and 4 of Confronting American Labor, 65-100. See also Ch. 3 in Daniel Geary’s Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought (2009), 74-105 and Ken Mattson’s Intellectuals in Action: The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945-1970 (2002), 52-56 for Mills’ evolving views. ↩︎

- Coker traces Sidney Lens’ views in Ch. 5 and 6 of Confronting American Labor, 103-139. ↩︎

- Coker, 51. ↩︎

- Coker, 58. ↩︎

- Coker, 186. ↩︎

- I am confident that Silverberg read articles in The Nation by Harvey Swados (1920-1972) (stay tuned!). I make the argument that Simak either read C. Wright Mills’ The New Men of Power (1948) or a review of it. ↩︎

- See Dubofsky and McCartin, 314-320. ↩︎

- Fones-Wolf’s Selling Free Enterprise, 266-270 explores the impact of the McClellan Committee. ↩︎

- I snagged my information on the craze from this wonderful survey article. It contains a bibliography that I am keen to read; See the August 2nd, 1954 issue. ↩︎

- A bit of soda-related trivia, Coke Cans first appeared in 1955! Coincidence? Hah. ↩︎

- In addition to “Hunter Patrol” (1959), I’ve identified the following (I assume there are more): “The Mercenaries” (1950), “Day of the Moron” (1951), “The Null-ABC” (1953), and “The Edge of the Knife” (1957). ↩︎

- Closed-shops require the hiring of only union members. They were declared illegal under the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 yet, while not written into contracts, were still used by employers who depended on unions for hiring: Source. ↩︎

- See Matthew W. Dunne’s A Cold War State of Mind: Brainwashing and Postwar American Society (2013) and Charles R. Acland’s Swift Viewing: The Popular Life of Subliminal Influence (2012). ↩︎

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Do you know H. Beam Piper’s “Day of the Moron”? (Astounding Sept 1951)

Never mind! I should have read the footnotes first.

Hah, no worries! But yes, I have it on my list of union-related Piper stories — “The Mercenaries” (1950), “Day of the Moron” (1951), “The Null-ABC” (1953), “The Edge of the Knife” (1957), and “Hunter Patrol” (1959).

Apparently Campbell wrote Piper a letter about “Day of the Moron” to tone down the anti-union rhetoric lest the union printers of the magazine got offended… I wonder if the letter exists somewhere I could read it.

I don’t know if the letter exists, but unless my memory has really gone haywire, Campbell published a notice in a later issue of the magazine reassuring the readers that the story didn’t mean that Street & Smith was anti-union. I’ll do a quick rummage and see if I can find it.

Yep, December 1951, “The Analytical Laboratory,” page 60.

Thanks! I’ll give it a read. Maybe it’s the “letter” referenced in the article I linked.

I saw it referenced in Olav’s intro article to his union list (which I’ve contributed all the stories I’ve found over the last year or so). The article with the reference: https://hugoclub.blogspot.com/2018/12/imagining-future-of-organized-labour.html

The full list with my additions: https://hugoclub.blogspot.com/2018/12/organized-labour-in-science-fiction.html

Here’s the letter, quoted in John F. Carr, H. Beam Piper: A Biography (McFarland & Co., 2008), p. 81:

In this interesting letter from January 15, 1951, Campbell wrote to Piper’s first agent, Frederik Pohl, regarding the short story “Day of the Moron”—a story about nuclear reactors and human error that is prescient of the Three-Mile [sic] Island incident.

Dear Pohl:

Please tell Piper that this one, as set up, is too hot for us to handle. It’ll have to be changed slightly. As set up, it’s enough to make most union men ready to chaw [sic] the handiest publisher’s representative; this we consider an unhealthy phenomenon, as we need publisher’s representatives.

The thing to do is to make it clear that the union officials have been misled by misinformation from the two discharges, and are equally aware of the necessity, once they get the true picture. In other words, the union isn’t to blame, but the individuals are.

. . . And it could be done fairly readily by installing a scene in which the union leader confers with the fired shop steward and organizer, and is given deliberately misleading information. [Ellipsis in book—no indication whether material was omitted, or Campbell just liked to throw in those periods for nuance.]

Point is—we got unions too, you know.

Regards,

John W. Campbell, Jr.

Editor [Note 7]

[Endnote text: John W. Campbell, letter to Frederik Pohl, January 15, 1951, p. 1.]

Piper made the necessary changes and “Day of the Moron” appeared in the September 1951 issue of Astounding. Piper appeared willing to listen to editorial suggestions, especially if it meant a sale; a sound practice for a budding author. What’s unusual about this letter is watching the legendary John W. Campbell back away from a fight—although New York unions in the fifties were easy to rile and he was probably right to be wary of putting his hand in that particular lion’s cage. Especially since most of the magazine’s distributors were Teamsters and could have easily refused to ship the magazine. Still, it’s a side of Mr. Campbell rarely seen in personal anecdotes or in print. [End of relevant text]

Thank you immensely! I purchased this biography a week ago but it hasn’t come yet. I wanted to read it BEFORE I wrote about his other more union-centric stories.

But my next thought is whether “Scanners Live in Vain,” which is not on your list, involves a union. It’s certainly about a group of people with the same job trying to protect their rights, though I get that that isn’t necessarily the definition of a union.

I’ll take any excuse to finally to get around to reading that story! I’ll relay the suggestion to Olav and the list I referenced in the other comment after I give it a read. Thank you for the suggestion (and any others you might think of)!

I can’t really criticise “Top Standby Job” because you needed it for your themed article, but it is poor, as you say. It seems to be a very rough sketch for a much greater piece, the actual theme being rather inchoate. There doesn’t seem to be anything in it about how such an oppressive state could have come about.

Yeah, I read his account of a union man as a bunch of stale cliches but a great representation of the standard unions are corrupt criticism that emerged in the 50s due to the historical context I mentioned.

And as a story, I couldn’t even tell that it was PKD at all. It had very little of his spark or invention.

Interesting stuff! I’m sure the only one of these I’ve read is the PKD story, and even there the only detail that rings a bell is the “newsclown” bit. I would slot any anti-union sentiments expressed into his broader distrust of institutional power, in line with his preference for protagonists who are either hapless schlubs or dynamic captains of industry. He never struck me as particularly deep or committed political thinker, he preferred focusing on alternately more mundane or more philosophical themes, with politics occasionally used as a backdrop.

The one exaple I can remember of a union playing a part in a Dick story is the “Plumbers Union” in Martian Time Slip, and especially the boss Arnie Kott, sort of the villain of the story, who, interestingly, seemed very much exactly like one of those “captain of industry” type characters so typical for PKD: Larger than life, enterprising, entitled, ruthless. Despite being a union leader, he could just as well have been a business magnate.

Yup, that one was on the list already that I contribute to. I remember adoring Martian Time-Slip when I read it before my site. I wonder what I would think now. Here’s the full list with most of my contributions (some haven’t been added yet): https://hugoclub.blogspot.com/2018/12/organized-labour-in-science-fiction.html

Once Internet Archive is back up (unfortunately it was hit wit ha DDoS attack) I’ll go back to to the union search.

The deep suspicion of institutional power, and the role of unions, sounds like C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite camp of social 50s criticism. Mills shifted radically from his views of unions between The New Men of Power (1948) and The Power Elite (1956). I am not saying that he read these books (I almost 100% think that Simak at least read about The New Men of Power) but they reflected some of the dominate trends in perception of unions and institutions that existed at the time.

Yeah doesnt quite seem like the kind of thing PKD would read but who knows. Just reflecting the zeitgeist perhaps.

i dont recall any specific union theme in Martian Time-Slip (it’s been awhile) but I do recall rating it highly, and the narrative doubling back on itself stunt in the middle definitely left an impression.

I wouldn’t be too sure about what PKD hadn’t and hadn’t read. We tend to think of him as an out-in-left-field — and sometimes just deranged and addled — visionary, with the implications of naivete that carries.

But, forex, in his first novel, Solar Lottery in 1955, there’s material in it relating to John von Neumann, both von Neumann’s minimax theorem and his and Morganstern’s Game Theory generally.

Now this material is actually at that novel’s thematic center. But it’s arguable that Dick’s mention of it merely amounts to spurious window dressing — pseudo-science dressing atop the plot of what was, finally, just another Ace paperback SF novel published by Donald Wollheim.

Equally, though, it could be argued that precisely because Solar Lottery had to satisfy the average SF reader (and Wollheim), the layer of von Neumann-game theory superstructure had to remain functionally detachable window-dressing on top of its action — something the average reader could skim over without understanding it. Which doesn’t mean, it isn’t relevant to the novel’s theme or that Dick didn’t understand its relevance.

So where would Dick have heard about and read up on von Neumann and game theory? Well, he was raised and lived in Berkeley, CA., in the 1940s-60s, and participated in its culture, because he attended high school and the university there, and he went to parties and coffee shops where topics like that would come up, and frequented second-hand book stores where he’d find books about it.

C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite was absolutely another book that was common intellectual currency in Berkeley then. Berkeley’s a funny place — kind of in a time-warp even now, despite the changes that have hit it and the Bay Area generally. Decades later, you can look on the second and third floors of Moe’s Books on Telegraph Avenue (where PKD worked in a record store from 1948-52 and where Jonathan Lethem worked in the 1990s) or on the shelves of old hippie’s homes in the flatlands and still find dusty copies of the Mills next to, say, Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Heart of Motorcycle Maintenance and Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia.

Later on, when PKD moved to Orange County in the 1970s, he started reading wilder stuff, like the Gnostics and Eastern mystics. But, again, he may have to some extent been responding to what the loonier spiritual types there and in Los Angeles proper were talking about and reading.

Point was, PKD was always a reader and a semi-deranged scholar, as is very apparent if you ever dip your toe in the Exegesis.

Dick was very well read before he became a science fiction author. He’d been interested in Gnosticism most of his life. His early short story “Upon the Dull Earth” was apparently influenced by it, as was “The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch”, which was inspired by an “experience” which was clearly Gnostic in origin to him. The point I’m trying to make is, that it’s not the sanity of what the author is writing about that matters, it’s the literary value of these pieces that’s important. I think that “Valis” fails because it lacks a subtle literary merit, the same of which can be said about the “Exegesis”.

Sorry the filter ate your first comment. I compared both and they were quite similar. I always check my spam filter so if it happens again I’ll always make sure to unspam it — even if it is a bit later.

Yeah, I’m with you and Mark on this point. He’s obviously reading, as writers are prone to do, a vast variety of texts. Of course, in this particular instance re-unions, I’m not sure it’s a direct reference vs. engaging with common ideas that were in the 50s across various mediums and genres.

reading HG Wells’ “When the Sleeper Wakes” and this passage (which is in the context of a “Boss” who is controlling labor unions and seizing political power 200 years in the future from Wells’ writing) struck me as relevant to the evolution of the view of unions becoming an institutionalized power:

“That counter-revolution never came. It could never organize and keep pure. There was no enough of the old sentimentality, the old faith in righteousness, left among men. Any organization that became big enough to influence the polls became complex enough to be undermined, broken up, or bought outright by capable rich men. Socialistic and Popular, Reactionary and Purity Parties wer all at last mere Stock Exchange counters, selling their principles to pay for their electioneering.”

This is from 1898. In his characteristically visionary fashion Wells is 50+ years ahead of his time.

Interesting parallel. I’ve gone ahead and sent this example and your explanation to Olav at The Hugo Book Club Blog who maintains the list of SF on labor unions that I’ve been adding to. It was not included.

Thank you!

oh cool! Yeah earlier in the book when the would-be dictator is discussing his strategy for seizing power he references having to have obtained the cooperation of various labor groups/unions (those responsible for airplanes/airflight for ex.)

The book on the whole is a bit of a mess but as a much more cynical pushback against Edward Bellamy’s “Looking Backward” and other Fabian socialist utopia writings of the times it’s pretty interesting.

Fascinatingly it was also apparently the inspiration/source material for Woody Allen’s film “Sleeper”.