The following reviews are the 31st and 32nd installments of my series searching for “SF short stories that are critical in some capacity of space agencies, astronauts, and the culture which produced them.” Some stories I’ll review in this series might not fit. And that is okay. I relish the act of literary archaeology.

Philip K. Dick’s “Explorers We” (1959) reframes the triumphant astronaut’s return home as the ultimate horror.

James Tiptree, Jr.’s “Painwise” (1972) imagines the hallucinogenic journey of a post-human explorer severed from the experience of physical pain.

As always, feel free to join the conversation.

Previously: Clifford D. Simak’s “Founding Father” (1957)

Up Next: E. C. Tubb’s “Without Bugles” (1952), “Home is the Hero” (1952), and “Pistol Point” (1953)

A brief note before we dive into the greater morass of things: This series grew from my relentless fascination with the science fiction of Barry N. Malzberg (1939-2024), who passed away last month. Malzberg wrote countless incisive visions that reworked America’s cultic obsession with the ultra-masculine astronaut and his adoring crowds. As I am chronically unable to write a topical post in the moment, I direct you towards “Friend of the Site” Rich Horton’s obituary in Black Gate. If you are new to his fiction, I proffer my reviews of Revelations (1972), Beyond Apollo (1972), The Men Inside (1973), and The Gamesman (1975). The former two are relevant to this series.

Ed Emshwiller’s cover for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Robert P. Mills (January 1959)

4.5/5 (Very Good)

Philip K. Dick’s “Explorers We” first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Robert P. Mills (January 1959). You can read it online here.

Six astronauts–Parkhurst, Barton, Leon, Merriweather, Captain Stone, Vecchi–return to earth from a voyage to Mars, “that damn red waste. Sun and flies and ruins” (89). But they are not met by adoring crowds as they stumble from their spacecraft. “Silence” screams that something is amiss (90). As they wander across a field towards the town, suburbia empties at their approach. People abandon their meals at diner counters. Workers abandon their jobs. Children dart away on bicycles.

I find the “war veteran returns home” a helpful correlate for stories that explore an astronaut’s return to Earth. In this instance, Dick wants the reader the visualize the standard shape of the narrative, the excitement, the expectation, the sense that normality might return. Like a soldier after campaign, Dick’s astronauts imagine the power of simple pleasures: Parkhurst fantasizes about visiting Coney Island, “I want to see people again. Lots of them. Dumb, sweat, noise. Ice cream and water” (89). Vecchi’s eyes shine as he imagines the touch of a woman: “Long time, six months. […] We’ll sit on the beach and watch the gals” (89). As a group, they understand what each went through–the brotherhood of stress and separation–and await the reception they’ll receive “bight and feverish” (90).

As the astronauts wander from the wreckage of their craft expecting the fanfare of a successful voyage, the narrative carefully shifts. The reader expects a heroic welcome. These are the heroes from Mars! In Dick’s final reveal, a cryptic dread-generating ritual hints at an existential dilemma–an indecipherable attempt to communicate? A mindless matter generating technology? An alien attempt to infiltrate and subvert?. And in its final subversive incision, Dick suggests that humans could solve the mystery but are immobilized by fear: “we have to believe that they are plotting against us, are inhuman, and will never be more than that” (97). Humans are not interested in uncovering the wonders of the cosmos–a more primal terror dictates.

I found “Explorers We” a well-crafted existential terror. The story plays with narrative expectation and hints at a cosmic enormity that will, at least in this iteration, remain unknown. Highly recommended–especially if Dick’s better-known “Imposter” (1953) is your brand of SF.

For other stories about the less than heroic experience of return check out Barry N. Malzberg’s “How I Take Their Measure” (1969), reworked as the last section of Universe Day (1971), and John Sladek’s “The Poets of Millgrove, Iowa” (1966).

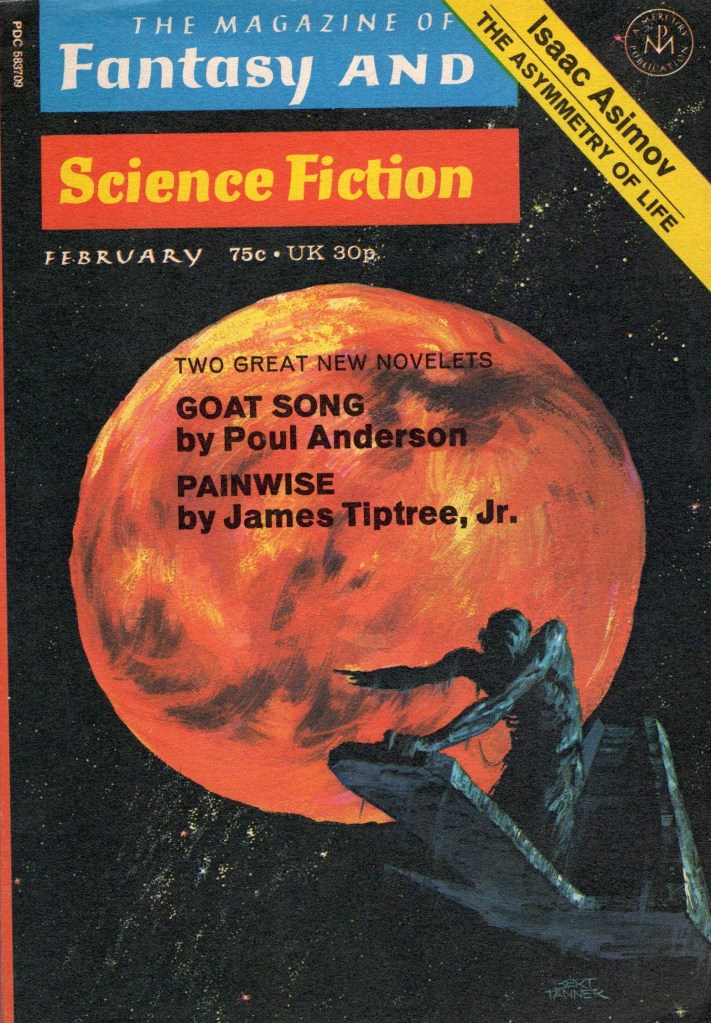

Burt Tanner’s cover illustrating “Painwise” for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Edward L. Ferman (February 1972)

4.5/5 (Very Good)

James Tiptree, Jr.’s “Painwise” first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Edward L. Ferman (February 1972). You can read it online here. Nominated for the 1973 Hugo for Best Novelette.

An explorer who feels no pain is hurled mercilessly from planet to plant where is he tortured, experimented upon, and broken again, and again, and again. His sense of time dissipates. Space becomes a hellscape that he cannot escape. And each time he’s lifted back to his scout ship where a mechanical boditech (Amanda), perhaps adopted from a real human brain, stiches him back together: “I am programmed to maintain you on involuntary function” (91). Pumped up on euphorics, he’s send down again. Each time he asks the Amanda if the trip is his last. Will he be heading home? He conjures a disturbing plan of self-harm to force the boditech to reveal a fragment of the truth: “they have forgotten us, Amanda. Something has broken down” (93).

Before he can ascertain the true nature of things, three strange empathic entities free him from the scout ship and Amanda’s ministrations. In the Lovepile, an “interstellar metaprotoplasmic transfer pod” (95), the three aliens, Bushbaby (a small fuzzy mammalian), Ragglebomb (an insect), and Muscle (a snake), engage in various acts of sensory immersion and overload. Tiptree’s prose inundates with fragments of jingles and popular songs, culinary references, sounds, colors… And the explorer, still unable to feel pain, joins in their cosmic quest to collect music, sexual experience, and food in the hope that he’ll find Earth. The smothering companionship of the Lovepile does not cover up other manifestations of pain and loss.

While reading the story, I could not escape the feeling that I was watching a cinematic immersion fantasia that overloads and bewilders the senses–the work of Peter Greenaway, namely The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989), and newer cinematic experiments like Peter Strickland’s In Fabric (2018) and Flux Gourmet (2022) came immediately to mind. Tiptree, Jr. (and Greenaway and Strickland) adeptly conjure a perverse blend of eroticism and desire, COLOR, the textures and delights of culinary experience, the grime of human existence, and excruciating pain. It’s a lot to take in.

In Tiptree’s final calculus, our drive to explore will compel us to act in the most inhuman ways possible. Like Simak’s “Conditions of Employment” (1960) and “Founding Father” (1957), humanity’s drive to act, exploit, and expand will always win out leaving human chaff in its wake. This is but a glimpse of the psychological impact of the ideology of cosmic conquest. Not to be missed if you’re of the predisposition to enjoy a kaleidoscopic, hallucinogenic, and surreal shuffle towards the end. Recommended.

I’ve reviewed multiple Tiptree, Jr. stories that fit this series over the years including “A Source of Innocent Merriment” (1980), “A Momentary Taste of Being” (1975), and “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” (1976).

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Philip K. Dick wrote this piece on his return to SF after a two year absence writing general fiction, including “Time Out of Joint”, that emerged from that failure to make it as a writer of realist fiction. I think this one shows a significant change in his writing too. As you say, it’s themes are existential. It’s concerned with memory, identity and what makes us human, but doesn’t provide any simple answers. The “astronauts” aren’t aware of their fakery and their humanity appears genuine.

I read “Painwise” through your link. Like other Tiptree pieces it’s very intense and opaque. It’s difficult to penetrate. She doesn’t hold back in matters of personal dilemma.

Like Imposter, PKD’s choice to not make the “imposter” know that they are an imposter is a sinister (and brilliant) choice. But yes, it’s intense, distilled, and deeply effective.

Yes, they’re concerned with knowing who and what we are.

Yeah, such a human desire adds such a creepy twist to the entire thing.