Note: My read but “waiting to be reviewed pile” is growing. Short rumination/tangents/impressions are a way to get through the stack before my memory and will fades. My website partially serves as a record of what I have read and a memory apparatus for future projects. Stay tuned for more detailed and analytical reviews.

1. Margo Bennett’s The Long Way Back (1954)

Uncredited cover for the 1955 edition

3.25/5 (Above Average)

I’m always on the lookout for lesser-known SF works by female authors. And Margot Bennett’s The Long Way Back (1954) certainly fits the bill. Bennett (1912-1980), a Scottish-born screenwriter and author of primarily crime and thriller novels, lead a fascinating life before her writing career. During the Spanish Civil War, she volunteered for Spanish Medical Aid, and was shot in both legs. Afterwards, she continued to participate in various left-wing political causes such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

The Long Way Back manifests, with satirical strokes, her critical stance on nuclear war and British colonialism. In a future collectivized Africa ruled by a calculating machine that grades the population, Grame, a “mechanical-repetitive worker” (7), dreams of a career in physics. Instead, the machine shuffles him off on an ill-fated expedition to the ruined remains of Britain post “Big Bang” (nuclear blast). On the way he falls in love with the leader of the expedition, Valya, who serves as a virginal Bride of the State (24). After their sea plane lands, they are beset by a bizarre range of mutations–ferocious dogs, micro-horses, etc. Eventually they discover a tribe of hairless white survivors holed up in primitive caves. Grame teaches the brightest arithmetic. Valya sets about measuring and applying pseudo-scientific theories to understand white society, religion, and conception of the world i.e. parroting all the pseudo-science and racist theories posed by British explorers of Africa. As they attempt to find a lost city, Hep, the third surviving member of the expedition, imagines the potential exploitation and colonization Africa might implement—“Yellow America” is on the rise and resources will be needed. History threatens to re-cycle through the horrors of the past in more ways than one.

The Long Way Back fits into a genealogy of British and American disaster novels that imagine future African supremacy and eviscerate the colonial mentality: two later works immediately come to mind, John Christopher’s The Long Winter (1962) and Norman Spinrad’s “The Lost Continent” (1970). If you know of more, let me know. While not a lost masterpiece, The Long Way Back remains an interesting experiment, especially if you’re interested in science fictional takes on Africa and post-apocalyptic nightmares.

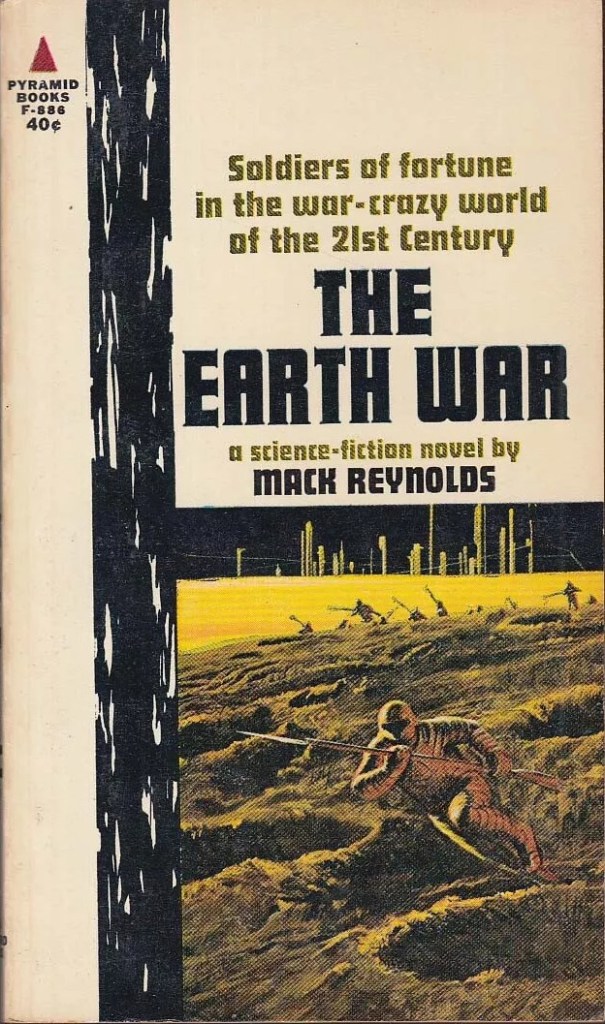

2. Mack Reynolds’ The Earth War (1964)

John Schoenherr’s cover for the 1st edition

2.75/5 (Below Average)

First serialized as “Frigid Fracas” in the March, April, and July 1963 issues of Analog, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. I am unsure how much was modified for the 1964 novelization.

In part due to my recent focus on science fiction that references the organized labor movement, I decided to return to Mack Reynolds after a fourteen-year hiatus. Reynolds’ radical political affiliations intrigue me. Recently I’ve been searching through his vast oeuvre for references to unions and sending them off to Olav at the Unofficial Hugo Book Club Blog to add to his list. Writing reviews of my contributions to the list is a much slower process!

The Earth War (1964), the second in Reynolds’ sequence that charts the adventures of a mercenary named John Mauser, charts our hero’s attempt to marry the woman of his dreams and win promotion to “that one per cent on top” (17). The Sov-world and the West-world no longer fight the Cold War through proxies or nuclear fear. The Universal Disarmament Pact removed all possibility of conflict. Instead, the desire for blood within the West-world is satiated by televised conflicts between various corporate entities fought entirely with weapons predating 1900.

In the first section, Mauser enters into an alliance with Freddy Soligen, a crafty advancement-seeking television man, to craft a heroic TV persona (replete with theme music) to advance both of their careers. After Mauser heroically represents United Miners in a brutal televised fight, he runs afoul of global law and falls from grace. In the second half, Mauser becomes a military representative conducting a clandestine operation in the Sov-World (USSR). As expected, the narrative points predictably slot into place and opportunities for fascinating battle sequences and thrilling undercover action tail off with little impact.

As expected, the oddly bland, unbalanced, and unrealized plot, plays second fiddle to Reynolds’ political ruminations. Reynolds posits a post-scarcity dystopia of People’s Capitalism (i. e. “Industrial Feudalism” combined with “Welfare State”) in which a rigid class system dominates society and the masses gobble up brutal entertainment. Only a few classes–in particular Military and Religion–provide an opportunity for advancement. I found the crafting of Mauser’s persona, and all the clubs and heroic (memeable) moments, the most interesting moments of the story. Unfortunately, Reynolds’ radical shift in plot–in order to ruminate on the evolution of the USSR’s futuristic communism (of which he is equally critical)–diminishes all forward momentum.

And the unions? Reynolds positions unions as part and parcel of the capitalist state in the relentless drive for profit. Rather than force for radical change, the unions and companies put mercenaries in the field to violently litigate differences (37). Mauser is hired by United Miners to fight against Carbonaceous Fuel (44). The union, as contracts only exist for two years, periodically enter fights to win a larger share of the corporate profit (45). Reynolds posits that historically “strikes [were seldom] held to better the condition of the individual union members” and instead were designed to increase coffers at the disposal of their “despotic” leaders (46). In Mauser’s day, the unions retain little of their original purpose as few working class jobs even exist due to automation (46). As unions collect a slice of each ton mined, with more effective technology the coffers grow exponentially and are utilized by union bosses instead of divided out among unemployed miners (46). I wonder if Reynolds’ was inspired partly by the McClellan select committee investigations (1957), watched by more than a million viewers on live television. I need to read more about the hearings in order to make more explicit parallels between negative SF takes and contemporary events.

Interesting only the for political discussions about the need to break from the cyclicality (Marxist-inspired) of history to escape new manifestations of age-old oppression. Reynolds struggles to craft the battle sequences and instill any thrill into the proceedings.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

The Bennett sounds fascinating and somewhat up my alley. I agree with you on all points re: the Reynolds, which I gave three stars seven years ago. Reynolds has some brilliant visions, but his writing is workmanlike at best.

Thank you for covering these!

The Bennett is a hard book to find. If you end up reading it, let me know. It’s a strange amalgamation of satire and genre tropes. The Reynolds was a bit disappointing (but expected considering what I know about his work). You’d think that a corporate battle with pre-1900 weapons could be rendered in an exciting manner… but the only exciting moments were the political ramblings (which, in case it wasn’t clear, was the only reason I read the book, haha).

I want to get more into Reynolds for the politics but I’ve mostly read short stories. I once saw a Goodreads reviewer slam him for working in “third camp Trotskyist burlesque.” I think that one was in response to The Rival Rigellians. It’s a technically inaccurate description of course but is true enough in substance to tickle me.

Hello William, sorry for the delayed response. It’s been a rough semester of teaching. I write and “do website things” for brief bursts on the weekend.

A few months back I sent mention of Reynolds’ The Rival Rigellians to Olav, the unions in SF list compiler, and he read the novel and said it was a fascinating dialogue between various political camps on the nature of labor. It seems to have been a far more positive view of unions than the more dystopic formulation here.

Reynolds political musings are always the only reason to read a Reynolds novel. It’s always a disappointment to find Reynolds wasting time with the “mandatory” action scenes in these types of “sci-fi” novels. You want him to get back to the interesting parts.

It’s well outside of your timeframe for this site, but In the United States of Africa (originally published in 2006) by Abdourahman A. Waveri, an author from Djibouti, is a stellar example of future African supremacy and an inversion with UK/Europe. After a series of major wars (including the most recent between Canada and US) followed by economic collapse, poor European immigrants are attempting to find refuge in the recently united African Union.

I agree on the Reynolds assessment for sure! Do you have any favorite Reynolds works for the quality of their political ruminations?

In the United States of Africa certainly sounds fascinating.

I’d actually give the nod to Time Gladiator for Reynolds actually. It’s the final novel in the “Joe Mauser” series, although Mauser figures very little in this one.

Time Gladiator is a mix of Brave New World and 1984, with some discussion about fascism, Trotskyism, Stalinism along the way. I describe Time Gladiator as a truly subversive novel.

Ah, yeah, Anthony recommended the first in the sequence — “Mercenary” — as well.

I’ve read both. Though in the case of the second, I read the magazine version, ‘Frigid Fracas’. I’ve also read the sequel, ‘Time Gladiator’. The first of the Joe Mauser stories, ‘Mercenary’ (1962), is the best. Reynolds grim satire of 1950s and 60s capitalism sparkles through there most freshly. TV entertainment taken to its grisly end. All the world building you mention is all there in the first, fully fleshed out. But it exhausts itself there too. In a better world he would have just written ‘Mercenary’ and moved on.

I read Bennett’s “The Long Way Back” sometime over the last ten years, before 2020, so I don’t remember it too well. I do recall that I liked the world building in the African states at the beginning more than when the books arrived in the wasteland of the North. I also remember liking the section in which the explorers traverse the ruin of an A-bombed large city later in the novel. It works best as a materialist critique of the racism and racist assumptions of her time, inherited in part from the then rapidly unravelling colonial empire of the Brits. Definitely a more interesting work of SF than most written in the 1950s.

Re-the Africa in the beginning of Bennett’s The Long Way Back: I was reading recently in Carroll’s Speculative Whiteness: Science Fiction and the Alt-Right (2024) how SF authors often present future societies of non-white individuals as “racially collectivized” to imply their inability to think independently (and thus imply the suitability of a future white society instead). Heinlein’s abominable Farnham’s Freehold is a good example. I wonder how Bennett’s overtly satirical manifestation of Africa fits into that trope. She obviously follows a group of independent thinkers who chaff against their society — while white British survivors live in holes and learn basic math from their visitors… I still think she dabbles in some unintendedly muddy ground (or perhaps it’s deliberate) in an attempt to attack British colonial mindsets.

“Racially collectivized” is a good descriptor for most non-humans in SF, demonstrating no doubt how the explicit racism of Heinlein, for example, lives on as the species-ism of SF (Star Trek in all of its guises is a great example of this).

The monolithic society — be that alien or human — remains my most persistent pet peeve. Writers just need to look at a chart of all the branches and denominations of any religious movement and apply a bit of the same diversity of belief to the worlds they create.

Didn’t see the Reynolds review until now since I’ve been working on my own review backlog more than reading other blogs. I’ll link to it.

In a bit of synergy, I learned that Charles Moyer, noted labor activist and radical affiliated with the the Western Federation of Miners mentioned by Reynolds, first joined a miner’s union in my home town.

I really would like to know the evolution of Reynolds’ view on labor unions. HIs complaints echo what you see in James Burnham’s The Managerial Revolution.

I feel like you could be the person who writes up his evolving views as you have read far far far far more Reynolds than me. I’ve been following your recent reviews.

Pingback: “The Earth War” — Just a Reviewer Parallax – MarzAat