In the past few months, I’ve put together an informal series on the first three published short fictions by female authors who are completely new to me or whose most famous SF novels fall mostly outside the post-WWII to mid-1980s focus of my reading adventures. So far I’ve featured Carol Emshwiller (1921-2019), Nancy Kress (1948-), Melisa Michaels (1946-2019), and Lee Killough (1942-). To be clear, I do not expect transformative or brilliant things from first stories. Rather, it’s a way to get a sense of subject matter and concerns that first motivated authors to put pen to paper.

Today I’ve selected an author I’ve never read–Eleanor Arnason (1942-). According to SF Encyclopedia, most of her best-known science fiction appeared from the mid-1980s onward with To the Resurrection Station (1986) (which I own), A Woman of the Iron People (1991), Changing Women (1992), and the Hwarhath sequence (1993-2012). Unfortunately, I did not encounter her work in my late teens and early 20s when I read science fiction more widely.

I’d rank Eleanor Arnason’s first three published short fictions as the most auspicious start of the those I’ve covered so far. Her stories–often self-consciously in dialogue with pulp worlds and plots–demonstrate a fascination with ritualized landscapes and behaviors and feature female narrators attempting to find their place in strange new worlds.

Let me know which Arnason fictions–perhaps from much later in her career–resonate with you.

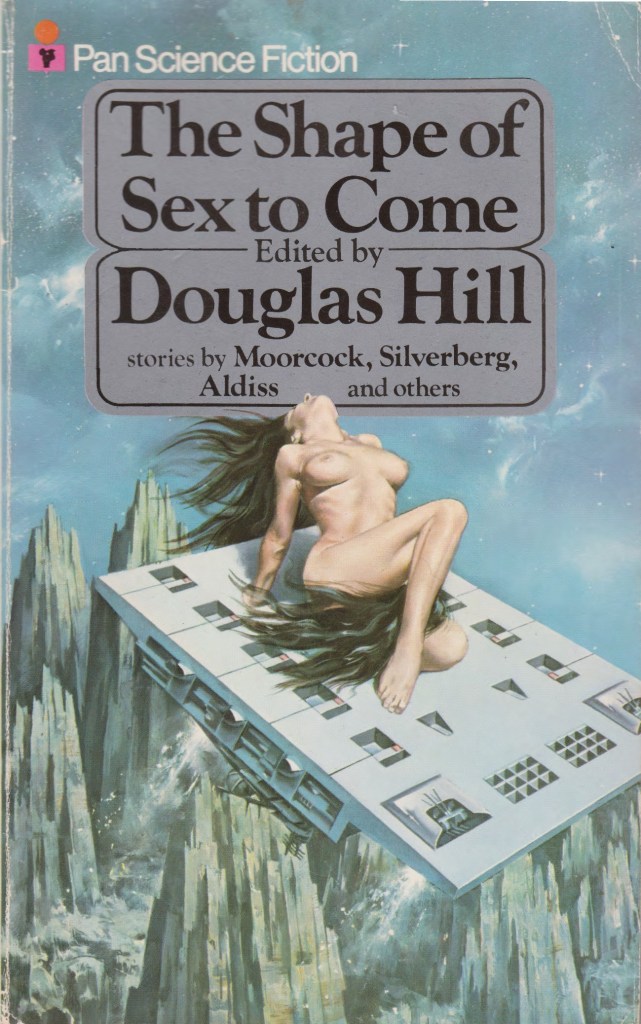

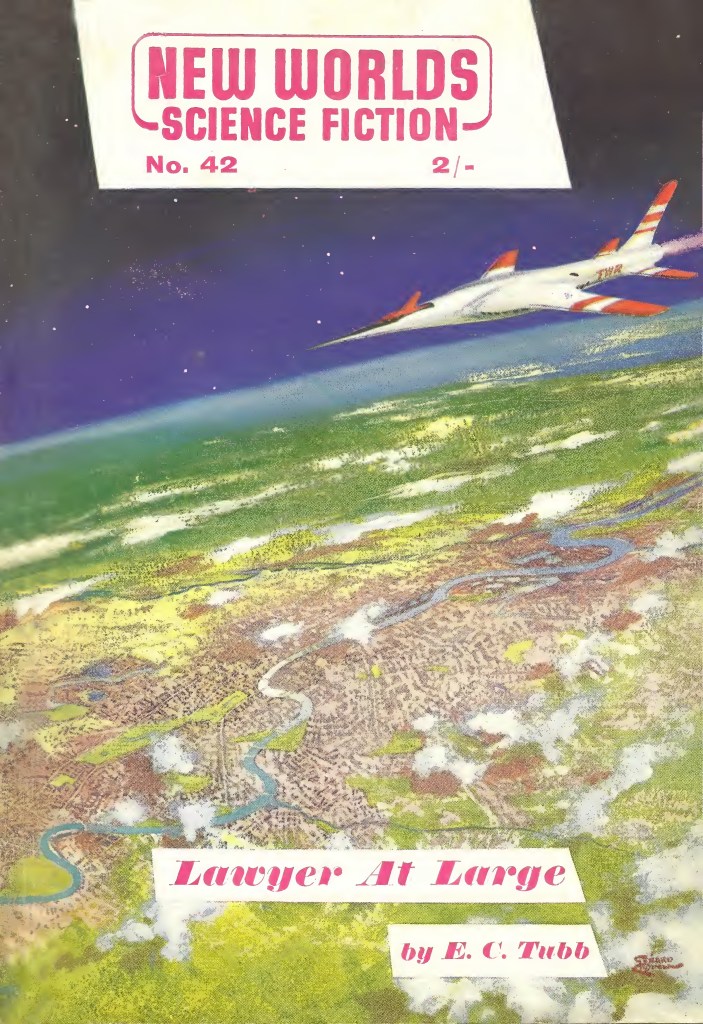

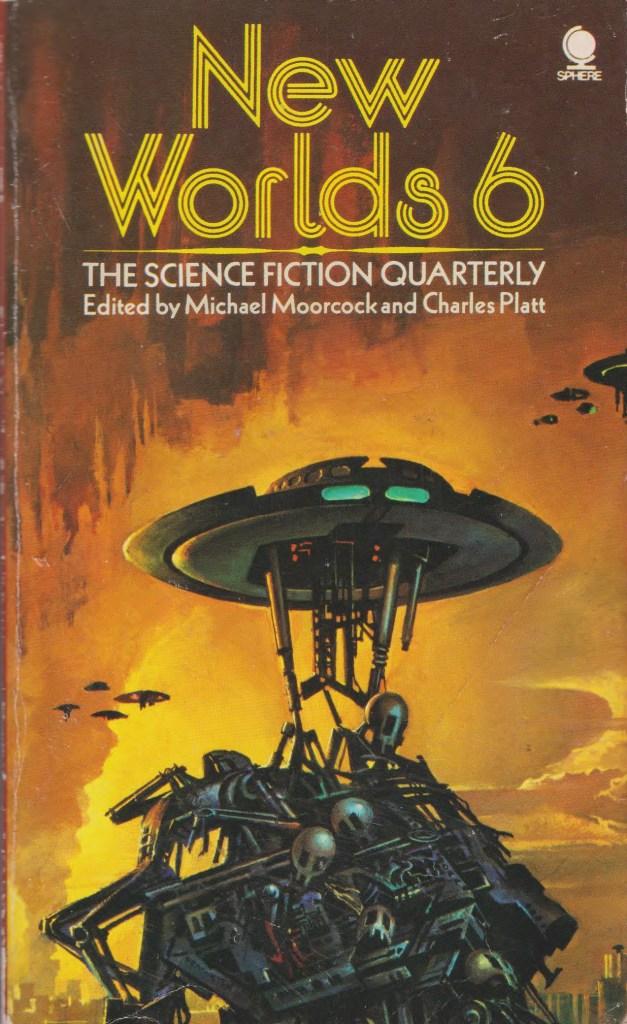

Bruce Pennington’s cover for New Worlds 6, ed. Michael Moorcock and Charles Platt (1973)

4/5 (Good)

“A Clear Day in the Motor City” first appeared in New Worlds 6, ed. Michael Moorcock and Charles Platt (1973). This does not seem to be available online. If you find it, let me know.

Like a cryptic quilt, a strange ritualized landscape drapes across the polluted industrial expanse of Detroit and Windsor. On clear air holidays, when “the Seven Sisters” were visible from the roof of a nearby office building, CEOs adorn “wreaths of plastic oak leaves” and release pigeons to “whoever’s responsible for the weather, to bear our thanks to him, her, it or them” (187).

Continue reading