The seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth stories in my series on the science fictional media landscape of the future appear in the anthology Tomorrow’s TV, ed. Isaac Asimov, Martin Harry Greenberg, and Charles Waugh (1982).

Previously: Two short stories by Fritz Leiber.

“The Girl with the Hungry Eyes” (1949)

“A Bad Day for Sales” (July 1953).

Up Next: Ann Warren Griffith’s “Captive Audience” (August 1953).

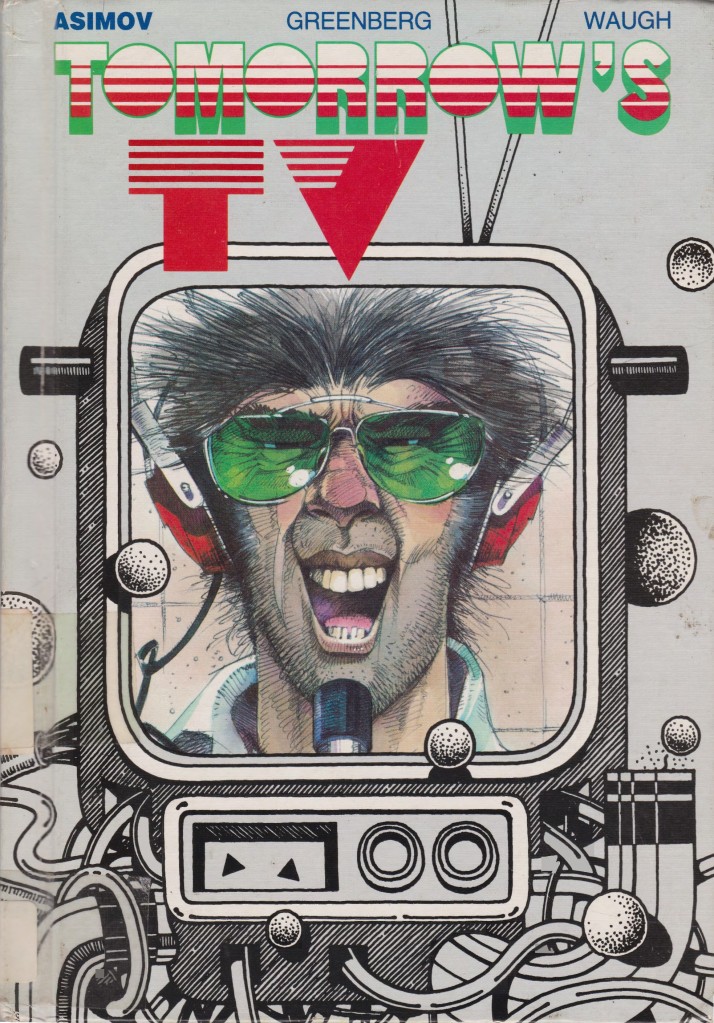

Greg Hargreaves’ cover for the 1st edition

3.25/5 (collated rating: Above Average)

Tomorrow’s TV (1982) gathers together five short stories published between 1951 and 1979 on future speculations and disturbing manifestations of the tube of the future. The extensive number of TV-related science fiction from these decades (especially the 50s and early 60s) should not come as a surprise. According to Gary R. Edgerton’s magisterial monograph The Columbia History of American Television (2007), no “technology before TV every integrated faster into American life” (xi). Isaac Asimov speculates on the nature of education and the role of the “teacher” if every kid goes to school on their TV. Ray Bradbury imagines a frosty world where everyone turns inward towards the hypnotic glow of their TV sets. Robert Bloch explores the intersection of programming as escape and its collision with the real world. Ray Nelson narrates a hyperviolent expose of the alien entities behind subliminal messaging. And Jack Haldeman II imagines what will happen when the human mind reaches a moment of information overload.

This short illustrated anthology is recommended for fans of future media-themed science fiction. Other than Ray Bradbury (and perhaps Ray Nelson), none of the stories are that memorable.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis

“The Fun They Had” (1951), Isaac Asimov, 3/5 (Average). You can read it online here. “They Fun They Had” is an Asimov tale written for the “Boys and Girls page” of the NEA Service newspaper which appeared three years later in the February 1954 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Margie and Tommy go to school on their personal TV sets. They insert their tests and homework papers (programmed in punch code) and the program progresses and reteaches at the speed of the student. Tommy finds an old book printed on paper about a physical school with a human teacher. Margie proclaims: “A man? How could a man be a teacher?” (11). But something about the community of the school, the real interactions, appeals to Margie… and she daydreams about the book and the past world and “the fun they had” (14).

This is a slight story written deliberately for a YA audience. Regardless, it provides an appealing slice-of-life feel and a brief speculation on the seductive nostalgia of the past. And, in the age of eLearning, there’s something deceptively powerful about memories of the world that must have been yet never was.

“A Scientific Fact” (1979), Jack C. Haldeman II, 3/5 (Average). You can read it online here. This satirical tale suggests that the TV relentlessly conveys so much information that at some point mass psychosis will prevail. Crazy Joe Wobbles plays “ten solid hours of Alka-Seltzer commercials” on the air causes his teenage fans to go wild (16). Carl falls flat on his face chanting “drugstore, drugstore, drugstore” (15). And Dr. Williams has a theory: “the box is a brain” and like “cards into [a] box” eventually “they both get full” (19). The President agrees that “Tube Fever” will eventually capture all. But other than the TV, how will the message be conveyed? One more card will have to fit into the box… and so the president introduces a short film to explain the crisis.

Information overload in the pre-internet age! As SF on media trails off in the 70s, until revival due to the cyberpunk, I read this one eagerly. This was definitely more successful than Jack Haldeman II’s “Sand Castles” (1974), the only one of his works I’d previously read.

“The Pedestrian” (1951), Ray Bradbury, 4/5 (Good): You can read it in online here. Previously reviewed for this series here.

“Crime Machine” (1961), Robert Bloch, 2.5/5 (Bad): You can read it online here. Stephen, “because his father was rich,” has his own “viddie set” (30). He immerses himself in the world of the “Good Old Days” — TV shows about Dion O’Bannion and Hymie Weiss and Al Capone and Arnold Rothstein…. His uncle is an inventor and his only successful invention, a subjectivity reactor, resides in a warehouse. Stephen discovers the reactor and soon the fantasy world of the TV collides with the real world. And Stephen must grow up, fast! As with the Asimov story, Block explores the seductive nostalgia of the past as conveyed through the screen. The effect is diminished with the introduction of the ridiculous subjectivity reactor.

“Eight O’Clock in the Morning” (1963), Ray Nelson, 3.25/5 (Above Average): You can read it online here. In the 1950s, the concept of brainwashing gained popular traction. Matthew W. Dunne lays out its history in A Cold War State of Mind: Brainwashing and Postwar American Society (2013). The following two paragraphs of historical summary are based on his work.

The concept, coined by Edward Hunter in 1950, gained popularity due to a series of events shocking to the American mind after the Korean War. According to Dunne, the publicity surrounding a group of American soldiers in Panmunjom who refused repatriation to the Untitled States in 1953, “signaled the arrival of brainwashing phenomenon” (Dunne, 14). Why would American soldiers refuse to come home? Why would good American boys espouse Communist propaganda and refuse to listen to the pleas of their friends and relatives? Journalists and others hypothesized that their behavior was not the simply the actions of traitors but rather new advances in “psychological torture and mind control” practiced by Communist nations (Dunne, 17).

In the late 50s, the terror of Communist brainwashing collided with fears of the detrimental effects of consumer culture and advertising. In 1957, Vance Packard published The Hidden Persuaders, that quickly became a best seller and “the most frightening book of the year” (Dunne, 170). Packard’s main argument was that “politicians, corporate executives, and big business” were using “large-scale efforts” to “channel our unthinking habits, our purchasing decisions, and our though processes” via “insights gleaned from psychiatry and the social sciences” (Dunne, 170). Articles like Gay Talese’ “Most Hidden Hidden Persuasion” (Jan. 12th, 1958) ran in The New York Times with images of entire families of American consumers transfixed by their “larger-than-life television” sets. Angels (or demons) whisper in their ears targeted advertisements–including a prescription against subliminal ads! While Packard built off of other postwar intellectuals who criticized consumerism and modern advertisement, he offered new insight into how “American corporations used the tools of modern psychology” including word-association and subliminal messaging (Dunne, 171).

Ray Nelson’s “Eight O’Clock in the Morning” (1963), inspired by contemporary fears of subliminal messages omnipresent at the time, combines alien invasion with a critique of consumer culture and the advertising industry. In an increasingly hyperviolent sequence of events, George Nada realizes that alien “Fascinators” control humanity via subliminal messages on TV screens and posters. The alien lizards chant the mantra “work eight hours, play eight hours, sleep eight hours” and “Marry and Reproduce” to their oblivious victims (41). Nada goes on a rampage–and the world around him thinks he’s paranoid. Nelson’s direct prose adds to the terror: “George picked up a brick and smashed it down on the old drunk’s head with all his strength […] After a moment he was dead” (44). This is a smartly told story that reproduces American fears of the day in a direct manner. The perfect material for a film.

Tangent: The rare instance where the film adaptation—John Carpenter’s They Live (1988)–is superior to the source material?

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Which of these (would you say) is/are most similar to our world (present or past)?

Personally, I do not read SF thinking about how it’s most similar to the present. Instead, I think about why it was created and imagined at that point in time. The historian in me kicking into gear!

That said, it’s hard not to see a bit of the Ray Bradbury — turning inward to the world of our devices at the expense of intrapersonal relationships (although he only mentions TV) — in the contemporary world.

Thank you, Joachim. I remember that Ray Bradbury story and enjoyed it.

This was written when there were 3 US TV networks and now we have YouTube, streaming, etc.

You have probably been frequently asked this, but what writers seem to not be “creatures of their times”,

i.e., those writers who do not seem to write with the sensibility of the eras in which they live and write?

I’ve only read and seen a tiny fraction of what you have Joachim, but much of what I’ve read and seen seems to reflect (and not transcend) the contemporary perspectives of the authors.

My answer might seem a cop-out. Every writer is a “creature of their times.” We cannot respond to anything other than the world and time in which we live. Rather, modern sensibilities might retrospectively claim that authors somehow “transcend their times” but that’s coincidence. Or, that some writers wrote about topics that continue to capture our imaginations (also coincidence). That does not mean that some people didn’t have views that were different than the majority of their contemporaries — and that some of those views became popular later. They were still rooted in the era in which they wrote and could not have written what they wrote in any other time in history.

The Prize of Peril by Robert Sheckley; a case for this series?

Absolutely fits the theme and is a masterpiece! I mentioned it in my intro short article that started the series: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2022/01/22/the-media-landscape-in-science-fiction-short-stories-lino-aldanis-good-night-sophie-1963-trans-1973/

That said, I do not plan on returning to any stories that I’ve already reviewed. Here’s what I said before: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2013/03/12/book-review-store-of-infinity-robert-sheckley-1960/

I’m assuming you enjoyed it too?

Ah, You have written about it; yes thats a masterpeace.

Preceding reality TV in a chocking (!) way.

Yeah, I feel like I should reread it. Or maybe read more of Sheckley’s stories instead…

If any other potential stories that fit the theme come to mind, let me know. My list is growing every day.

I have a signed ex of Mindswap; got it at the SF-convent in Sthlm 1977. Sheckley was Guest of Honor. Harrison and Aldiss (surprice guest), among others was there. I was 19 and drunk every night; and so was those stars!

Ah memories!

I have a copy — but with no comparable memories or signature. Haha. Sounds like a fun time.

Now here’s an oddity. Asimov, Waugh, and Greenberg edited another anthology of sf stories abt TV also even published that same year, 1982.

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?52506

It includes Sturgeon’s “And Now the News” which I remember being a portrait of psychosis resulting from media overload.

Yup! I have that one on the shelf. Purchased a copy back in 2016. My acquisition post: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2016/03/15/updates-recent-science-fiction-acquisitions-no-cxliii-two-themed-anthologies-election-day-2084-and-tv-2000-harrison-gary/

I have not read the Sturgeon story yet. Sounds fantastic!

It’s one of the good Sturgeon stories.

I look forward to reading it!

Ballard’s “The Subliminal Man” (1963) is one of my favourite SF stories on the use of subliminal advertising. Perhaps you should add it to the list?

Nelson’s story is short and brutally effective, even if sans glasses. I have a sneaking suspicion that Carpenter added the glasses because he read the Nelson story in this collection:

The Ballard story is 100% on my list. It came to mind right away after reading D. Harlan Wilson’s monograph on Ballard that also spurred this series and my acquisition of Vance Packard, various McLuhan books (thanks for The Mechanical Pride PDF!), etc.

Did Nelson write anything else worth while? He’s not a name I see come up very often… or that I know much about.

I should write up something on the Ballard, seeing that it yet another of his stories that was seared onto my impressionable mind as a youth. Ballard has a lot to answer for for the way my life unfolded!

And your welcome re: the McLuhan.

I’ve only read one other story by Nelson: “Turn Off The Sky” (1963), which is an appealing tale of future bohemians in a global society in the early 21st century. I’ve been intending to read his co-write with PKD, “The Ganymede Takeover”, for years, but can’t seem to summon the enthusiasm. Is it possible that this was the work that originally was intended to be a sequel to “The Man in the High Castle”?

Hopefully my little summary of “brainwashing” and subliminal images in Nelson’s time that might also be helpful in contextualizing some general elements also found in the Ballard story. Albeit, from an American rather than UK perspective. I’m still finishing Dunne’s monograph — a great read so far. Although, D. Harlan Wilson’s monograph does a better job than I could identifying which texts Ballard drew on. I know I’ve talked that one up before with you!

As for PKD, I can conjure little motivation to return to his work. More due his perception/obsession in fandom than his actual stories… many of which I know (and have read before) would fit my media story series. That said, I have powerful memories of a short story of his with advertisements appearing in dreams… I can’t remember the title and probably would reread it for my media series.

I’ll keep my eye out for more of Nelson’s stories. He published a bunch of novels with Laser books that I’ve seen in stores but never purchased due to the reputation of the press.