My 1000th post!

Every morning for the last few years, I post on Twitter the birthdays (pre-1955) of artists, authors, and editors involved in some way with science fiction. In the last year, a singular compulsion has hit and I’ve started to include even more obscure figures like Gabriel Jan (1946-) and Daniel Drode (1932-1984). On May 31st, while perusing the indispensable list on The Internet Speculative Fiction Database, I came across an author unknown to me–Melisa Michaels (1946-2019) (bibliography). She’s best known for the five-volume Skyrider sequence (1985-1988) of space operas “depicting the growth into maturity of its eponymous female Starship-pilot protagonist” (SF Encyclopedia).

As I’m always willing to explore the work of authors new to me, I decided to review the first three of her six published SF short stories. Two of the three stories deal with my favorite SF topics–trauma and memory.

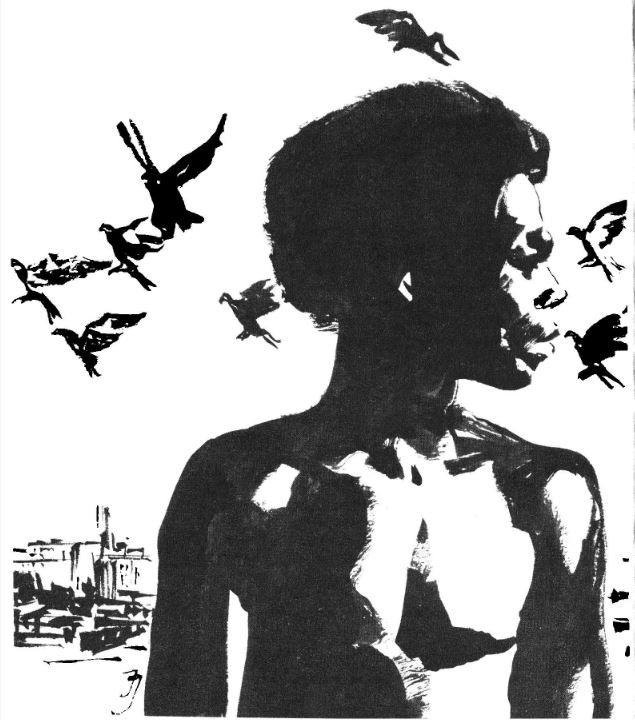

Karl Kofoed’s interior art illustrating Melisa Michaels’ “In the Country of Blind, No One Can See” in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (January 1979)

“In the Country of the Blind, No One Can See” (1979), 3.5/5 (Good): First appeared in Isaac Asimov’s Marvels of Science Fiction (1979). It was reprinted in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (January 1979). You can read it online here.

On a terraformed Mars, Allyson Hunter and her two clone sisters, Rebecca and Kim, are societal outcasts. They spent their lives trying to be “real people” yet were “reminded, every day in a dozen little ways, that they weren’t real people” (87). Clones retain their first usage as replacement body parts. Permitted to live only due to indications of telepathic potential (needed to guide spaceships), the sisters attempt to live meaningful lives and develop useful skills. The sisters charter two identical twins, Frank and Todd, to convey them across the Martian landscape. A horrific crash kills Kim and forces the survivors to work together and move past the deep resentment and hatred the brothers hold.

Continue reading