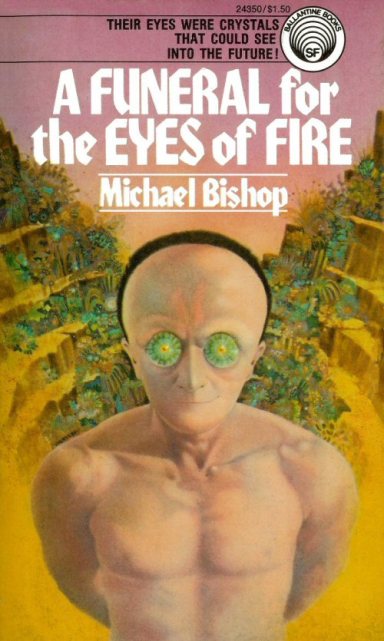

(Gene Szafran’s cover for the 1975 edition)

Nominated for the 1976 Nebula Award for Best Novel

5/5 (Masterpiece)

*First, a preliminary note on the publication history: I read the original, unabridged 1975 edition. However, Michael Bishop “completely rewrote” the novel in 1980 (according to ISFDB and his introduction to the later edition). The 1980 rewrite—initially titled Eyes of Fire but later confusingly released under the original title, A Funeral For the Eyes of Fire-–was the one republished and recently available as an eBook through SF Gateway according to Bishop’s wishes. I would prefer my readers, if they are interested in the volume, to not hesitate in snatching up the original. I suspect both are worth reading.

Fresh off Michael Bishop’s strangely wonderful And Strange at Ecbatan the Trees (variant title: Beneath the Shattered Moons) (1976) I eagerly devoured his first published novel, A Funeral for the Eyes of Fire (1975)—and with this work, bluntly put, he enters my pantheon of favorite SF authors. Bishop, completely in command of his narrative, weaves together a literary and anthropological tapestry filled with stories within stories and delicate interplay between these layers.

The deceptively simple premise unfurls into a complex and moving meditation on culture clash and the power of ritual, threatening at every moment to explode into violence. This is perhaps the most sophisticated rumination I have encountered on the clash of technology and religion in SF. Our hero, after escaping from his imprisonment in the domed cities of America, can only observe while societies crumble despite, in the words of Robert Ardrey so central to Bishop’s themes, the “guiding force” of his conscience.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis

Two human brothers, Peter and Gunnar Balduin, flee into space from the freedom-denying technocracies that are the domed cities of North America in part to “put money in their purses” (1). Peter, the elder more corpulent brother, weaves a web of hidden plans from behind the scenes. His young brother Gunnar, the main character of A Funeral, considers his elder brother a father-like figure, a dispenser of knowledge, or wisdom. Over the course of the work Gunnar will slowly see through Peter’s aura and escape from his influence.

Peter and Gunnar encounter two aliens, called Glaparcans, whose original names are abbreviated to Stephen and Anders. The Glaparcans have fleshy eyes, unlike the lensed eyes of man, and a strict hierarchy. Anders, is the calm one with a conscience (the double for Gunnar) while Stephen is abrasive and forceful (who doubles for Peter). Stephen never seem to completely understand his human allies and tolerates their human names “for the sake of smooth relations” (3). While Gunnar had “less difficulty imagining Anders” as human (3).

They have a proposition for their human “friends.” They will be the emissaries to the alien planet Trope to assist in the removal of a renegade group, the Ouemartsee, and in return will receive a substantial payment and the goodwill of the Glaparcans. If they fail, they will be returned to the domed nuclei of Earth.

Even the planet name, Trope, indicates established categories, the more mystical (mainstream Tropeans) and those guided by logic (Ouemartsee renegates)…. The planet, “the world of ochre and violet,” contains another humanoid races called the Tropeans (2). The Glaparcans are distinguished by their fleshy eyes, the Tropeans by their lack of mouths—they absorb food liquids through their palms—and crystaline eyes. They communicate amongst each other, and other species, via “encephalogoi” i.e. “brain words” (4).

The most important cultural ritual of the Tropeans, the dascra, is yet again an act of pairing, in this case the past with the present. The renegade Ouemartsee men, and I use this term loosely because there does not appear to be gender as we know it, take the crystalline eyes off the dead body of their birth parent (it is always in the singular) and divine their “Final Vision” before death (62). This is not a literal vision of what they saw before death, rather the “shamans told the people that the Final Vision was the apocalyptic upheaval in one’s being that surfaced at death and lodged in the mirrors of the eyes–an image of the soul itself” (63). After the ritual the eyes dissolve into dust, dust which each Tropeman wears in a bag around his neck: they carry the material that conveyed the image of their birth-parent’s soul.

The meaning behind the ritual held by the mainstream Tropeans and the renegade Ouemartsee illustrate the bigger interpretive paradigms at stake. The mainstream Tropeans hold the distant reforms of Sessbor Georlif in high regard. For them they illustrates a moment in the past where science and logic triumphed, in at least a partial way, over the forces of mysticism. The ritual of the dascra has symbolic meaning; it’s an emblem, explicitly genital, of manhood. For the Oeumartsee shamans, the ritual still holds its mystical ramifications, seeing the soul of the dead ancestor. The Oeumartsee are thus seen as outliers, those who have no bought into the progressive Georlif legacy, reminders of an outmoded “primitive” past. Non-Oeumartsee Tropeans, on the other hand, undergo multiple character transformations (Change Phases) over the course of their lives in an effort to “progress.”

Gunnar descends to the planet with little knowledge of the cultural values of the Glaparcans, the mainstream Tropeans, or the more mystical Oeumarstee. All he knows is that the Tropeans want the Oeumarstee removed from their planet and the Glaparcans want them relocated to their own home world to transform a desolate section of the planet. And Gunnar has to try to convince them to leave on their own accord.

And there is yet another pair, the two Oeumarstee characters: the old Pledgeson, or leader, and his adopted son, Bassern… The old man guides with a sure hand, while the young boy is more mysterious, and strangely elusive. Gunnar feels drawn to Bassern, despite the initial disgust with his appearance, “his head was misshapen and brutish looking, entirely without symmetry. His eyes stared at us from different levels above his uneven cheek bones” (95). Over the course of his “friendship” with Bassern he learns about their more mystical goals, awaiting the reappearance of their savior, Aerthu. He continues to struggle to look beyond physical differences; Bassern is transfixed by the differences as well: “‘Does it hurt you, Kahl Baluin? The noise-making-wound?’ He meant my mouth” (135).

The tensions increase, and the Oeumarstee clearly do not want to leave….

Final Thoughts

The novel verges on overwhelming. Because of the layers and layers of the novel and the careful pairing of characters, the obsession over ritual and the meaning of ritual, and how every interior story, however fragmentary it might seem, relates to the thematic core of the novel, I will select one particular instance….

In a remarkable prologue, “Loki is My Brother”, Michael Bishop sets up a series of parallels that will dominate every aspect of he novel. At one level the title refers to a Glaparcan myth told by Anders within the prologue. Anders asks Gunnar to insert a name from Earth mythology, i.e. Loki, in place of the complex Glaparcan name for the deity. In the myth Anders recounts how a thief figure, “without conscience” (10), acts out of instinct steals, honors no one, before official “Law” is created (11). When Law is created Loki rages and he is banished in the Obsidian Wastes, alone…. And after time he encounters an alternate version of himself imprisoned in the ice without hands, the version he could have become if he had stayed in the world of Laws. Loki turns his back on his doppelgänger because he is without conscience, an the embodiment of Conscience is trapped in the ice, the brutal land of ice that cannot be conquered.

Despite being a Glaparcan myth it relates to the human condition (Loki fits all too well in the narrative). Gunnar is a man with conscience but he is trapped in a world he does not understand and struggles to escape from. His brother Peter, a Loki-esque figure (i.e. the title of the prologue) is almost a man without conscience and conspires behind Gunnar’s back. Regardless of the progression of Gunnar’s character and his slow understanding of what is occurring he cannot escape from his prison, from the forces at play, from the cultural constructions. In short the myth applies to the thematic core of the novel and simultaneously the relationships between the characters. And then there are Oeumarstee myths, and they relate to the Glaparcan myths, and then there are Tropean myths and they interplay with the Oeumarstee ones.

Each piece is meaning imbued, each piece thought out and interrelated. And so many well-written works of literature, the beginning relates to the end, and Gunnar encounters an alternate “version” (allegorically) of himself.

Highly recommended for fans of anthropological and literary science fiction in the vein of Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969). I suspect Bishop’s own insistence that the original version is flawed has prevented the book from gaining a larger audience. But then again, Bishop’s popularity despite Gollancz’s reprints of Transfigurations (1979) and the Nebula Award-winning No Enemy But Time (1982), seems to be on the wane.

A Funeral for the Eyes of Fire is an achingly beautiful moral allegory on ritual and culture clash, on science and technology, and at its most primal, a coming of age story of mankind thrust into a world so much greater than their own. Yet, in a terrifying way, the forces that oppress and control amongst alien worlds are remarkably similar those inside the domed nuclei on Earth.

(Melvyn Grant’s putrid cover for the 1978 edition)

(Franz Berthold’s cover for the 1981 German Edition)

For more book reviews consult the INDEX

The cover alone is horrifying! I haven’t read a good sci-fi in a while, and you have just helped me choose my next read!

Make sure to read the publication history note at the beginning of the review. Obviously it’s your choice which version you want to read. Just know that the rewrite is completely different….

The cover is eery, that’s for sure, as is the book.

It really seems like the two versions have not much more in common than the barest plot outline. Seems weird that Bishop’s dislike for his first novel seems to be so intense, and not at all justified. But then, this would not be the first example of an author being a bad judge of their own work.

Anyway, it’s probably best to consider the novels as two different works that just happen to share a title and some plot elements and read both. 😉

Definitely.

All I can say is, find a copy! hehe

This is the first time that I have heard of this novel and it sound pretty interesting. I’ll try to pick a copy up on my travels. Is it widely available or something you picked up second hand?

Yes, it’s a wonderful novel.

As I mentioned in the first paragraph of the review, this version (he wrote a second “version” in 1980 which is really a separate novel) is long out of print and he refuses to republish it. I found it for a dollar at a used bookstore. But, if you can’t find a copy there’s always amazon (it’s 1 cent but you’d have to pay shipping of course).

Ooh, it sounds amazing.

Definitely inspired by Le Guin… Next time I read it I’m going to pay special attention to the strange gender dynamics. The aliens they encounter are all “male.” And children have a singular birth parent and he is very careful to say that male “nurses” take care of the children..

Thanks for the review! I’ve read Transfigurations by the author and loved it. I’m looking at picking up some more books by him.

I want a copy of Transfigurations!

This book sounds pretty interesting. Growing I too, like many others may have, have look to my older brother as a father-like. Thank you for this article, it’s very helpful.

Well, hopefully he didn’t involve you in human trafficking without your knowledge… like this brother did!

I ordered this from bibliophile on the strength of your review. I havent started it yet. At the mo I’m reading Timescape by Gregory Benford who is a physicist-sf writer. The novel reads like a straight novel in that he has good characterisation and it’s set in academia. Have you read it?

Cool.

Timescape is one of those books that’s been on my list for a long time. I don’t own a copy but I should keep my eyes out. I have a copy of In The Ocean of the Night (1977) but it’s not supposed to be that great…

I got to page 80 in Funeral for the Eyes of Fire and had to give up. There’s a lot of information dumping and the dialogue is a bit tedious. I wondered when the plot was going to launch! Hope I fare better with The Laft Hand of Darkness.

Alas. The Left Hand of Darkness is very similar actually, he was inspired by her work… This is DEFINITELY not a plot heavy book! I often point this out in my review but didn’t here because I was too carried away with what Bishop was saying.

I might tentatively warn you that lots of the SF I enjoy is not plot heavy and definitely on the more literary and experimental side. I found that A Funeral‘s highly metaphorical interior stories, the bizarre anthropological observations, the unsettling violence, and strange ruminative mood propels it to its heights, not an on the edge of your seat what’s going to happen next plot.

Thanks for another great find. I read the original 1975 edition. Have you read the rewrite? That I could not find. I would be curious to see what he did with it.

I agree with the 3 5/5 reviews I have read so far from your reviews – great books. Although I really think Aldiss’s Non-Stop deserved a 5/5 as well.

(I think if I reread Aldiss’ Non-Stop I’d up the rating to a 5/5 — one of the best of the 50s SF novels I’ve encountered.)

Thanks! I have not read the rewrite. It’s a completely different book.

Just out of curiosity, how can you say “it’s a completely different book” if you haven’t read it?

Warstub, did you read the second sentence of my review? I’ll quote the first paragraph: “However, Michael Bishop “completely rewrote” the novel in 1980 (according to ISFDB and his introduction to the later edition).” It’s Bishop’s own words + the assessment of the website isfdb.org with incredibly extensive bibliographies of most SF etc….

Yes, I did actually! But okay, I take your point that the description itself makes it seem like a “completely different book” though I wouldn’t equate a “complete rewrite” with that, though.

Sorry, I’m unnecessarily splitting hairs. It’s not important.

🙂

It would be interesting to read your thoughts on the second version, should you read that one day, as I had the feeling that really had a heavy plot. The two books seem to differ a lot (see my review for some details), yet from what I can gather the basic plot outlines do run parallel, so that kind of puzzles me.

I just finished this book. I got the 1975 edition from a library through interlibrary loan and it was fantastic on every level. I went to Abe Books and snagged what claims to be a copy of the 1975 edition (waiting on them to confirm the order with bated breath, because if they say no I’ll keep seeking a copy of the original). I am honestly stunned that Bishop thought the book needed a re-write, and according to the introduction to the version I grabbed on Kindle after finishing the book, apparently doesn’t ever want the original version back in print. I truly don’t get it, because the original seems to be a nearly perfect piece of science fiction. I wonder what the re-write is like, but saw in comments here it is substantially different.

I honestly don’t get it. How does someone write a book that’s so good and then not allow it to remain in print and even re-write it! I wonder what his reasoning was. Anyway, here’s hoping the seller on Abe Books has it in stock, because I desperately want the original edition in my library.

Thanks for stopping by! What element of the book fascinated you the most?

Yeah, the rewrite befuddles. I am curious about what was changed but I rather read his other works before I investigate the rewrite.

If you enjoyed this one I have two further recommendations (they didn’t appear on award lists).

His collection of connected short fictions of a domed Atlanta, Catacomb Years (1979): https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2016/01/01/short-sf-book-reviews-michaelmas-algis-budrys-1976-the-machine-in-shaft-ten-m-john-harrison-1975-and-catacomb-years-michael-bishop-1979/

And his nightmare vision of disease and resistance, Stolen Faces (1977): https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2014/03/26/book-review-stolen-faces-michael-bishop-1977/

When people mention that the late 70s weren’t exciting for SF, I always bring up Michael Bishop — a Joachim Boaz favorite!

(I hope I managed to put this in the right place, I’m responding to your latest comment.)

I just snagged “Stolen Faces” and a copy of the original version of this book (“Funeral…”) so I’m hoping they actually get sent this time (the last seller cancelled because they no longer had it in stock. I remember briefly chatting with you about how much I loved “Brittle Innings.” That book is so very different from this one. It’s amazing they’re the same author, but the one link is the intense focus on humanity.

I primarily loved two things about “Funeral…” The first: as you say, the command of the narrative, but also his command of the written word. I wouldn’t call it lyrical, but his prose is wonderfully clean and has a quality that I want to call haunting but I’m not sure that’s quite the right word. It’s just fantastic how many layers there are here, but not in an overwhelming way. The second thing I loved: the exploration of human nature and concept of “ritual” at the center of the plot.

I bought the re-write on Kindle, so I’m hoping to read that soon as well. I honestly want to read basically everything he’s written at this point.

I did get a collection from 2019 called “The City and the Cygnets” which is apparently a slight rework of “A Little Knowledge” and “Catacomb Years.”

Anyway, I’m not familiar enough specifically with the late 70s but I would say I’m fairly excited about a lot of the science fiction I’ve read from the 70s in general. And I know you scorn award lists, but such lists are largely how I’ve found authors I like without the luxury of time to really explore as much as you do with your research. I may never have read Michael Bishop were it not for award lists, for example.

You would have found Bishop if you browsed my highest rated books on my site!

https://sciencefictionruminations.com/science-fiction-book-reviews-by-author/sci-fi-book-review-index-by-rating/

Jest aside, the 70s are my single favorite decade for SF — as the list I linked above will make abundantly clear (as you know, only a small slice of what I’ve read).

As for reworked books, I’m glad more of his stuff is in print but count me out. I rather read the originals — not interested in authors returning to their earlier works and rewriting. I’m interested in what was published at that moment of time. Gives a far better sense of the decade and contemporary concerns and speculation of the day…. but that’s the historian in me I guess.

“Luxury of time”? I wish. You might notice — on most days I tweet in the morning at 5:30-6 am when I wake up and in the evening. I’m a teacher! Unfortunately, having time would be against the entire nature of secondary education in a Republican state with insufficient staff and funds. Alas. I’ve had a little bit more time this year teaching from home due to Covid. As I design all my courses the work load in and out of the classroom is immense. From your twitter account I suspect you read a good 6 times what I do in a year. A rate I only accomplished during grad school….

Pingback: Vintage Sci-Fi: “A Funeral for the Eyes of Fire” by Michael Bishop | Eclectic Theist