This is the 12th post in my newly resurrected series of vintage generation ship short fiction reviews. Today I have something a bit different — a 1970s commentary on the subgenre. While the story itself is not a generation ship tale as it takes place on Earth, it fits and critiques the theme from within a similar enclosed environment.

As a reminder for anyone stopping by, all of the stories I’ll review in the series are available online via the link below in the review.

You are welcome to read and discuss along with me as I explore humanity’s visions of generational voyage. And thanks go out to all who have joined already. I also have compiled an extensive index of generation ship SF if you wish to track down my earlier reviews on the topic and any that you might want to read on your own.

Previously: Arthur Sellings’ “A Start in Life” (1954).

Next Up: Vonda N. McIntyre’s “The Mountains of Sunset, the Mountains of Dawn” (1974).

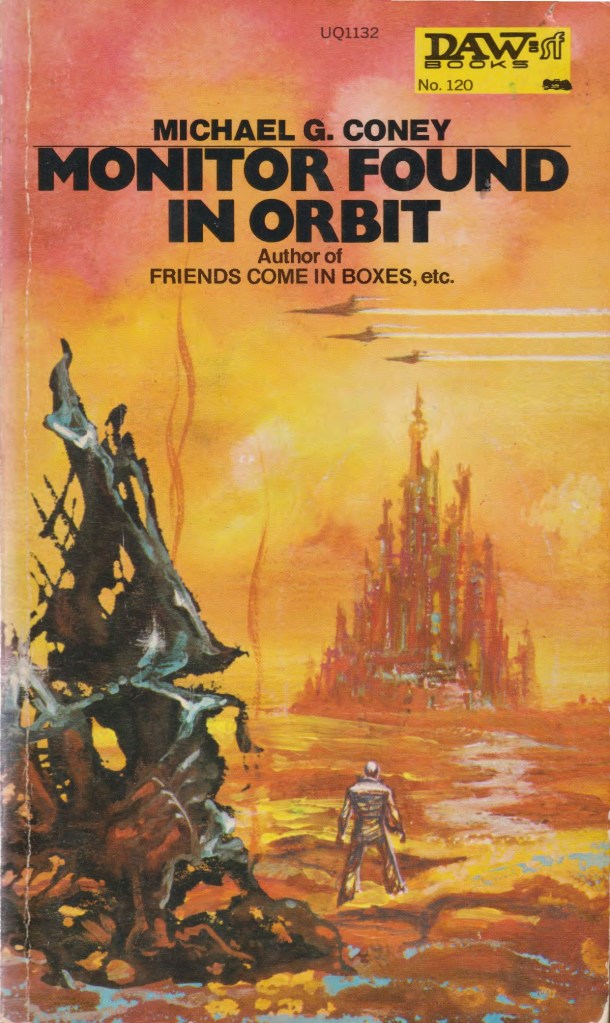

Frank Kelly Freas’ cover for the 1st edition of Monitor Found in Orbit (1974)

Michael G. Coney’s “The Mind Prison” first appeared in New Writings in SF 19, ed. John Carnell (1971). 3.5/5 (Good). You can read it online here. I read it Coney’s collection Monitor Found in Orbit (1974).

Coney positions “The Mind Prison”, in the introduction to his collection Monitor Found in Orbit, as a commentary on generation ship stories–in particular Robert A. Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky (serialized 1941) and Brian W. Aldiss’ Non-Stop (variant title: Starship) (1959) which he read and reread over the years. He writes: “I cannot explain why I find the closed environment story so fascinating [..] Why should an adventure story be more exciting, merely because the people therein are not subject to external influences?” (114). Coney emphasizes the centrality of male heroism in many of these stories: “I would rather think that these stories emphasize identification, since the hero is invariably the only normal person around, surrounded by nonsensical religions, illogical facts, widely held misconception, which only he [emphasis Coney’s] can see the stupidity of” (114). “The Mind Prison” explores an enclosed environment remarkably similar to a generation ship, with a female heroine.

The “gray concrete towers” of Festive, as if a fantastic permutation of Hashima Island in Japan, looms above the ocean (114). Originally a fallout shelter built to preserve its inhabitants from a nuclear war, Festive grows both upward and downward. Each new chamber is sealed off from the “poisonous air by men working in suits supplied with oxygen” created by a “vast complex of machinery humming beneath the sea” (114). The elderly Jeremiah, masked in an airlock from the poisonous exterior, flies mechanical pigeons–“an education pastime for all ages,” the box reads, “perfect replicas of birds now found only in remote Antarctica” (118). Jillie spends time with Jeremiah who shares his wisdom about the nature of the world. She wants to marry David, a political radical of the Stabilization Party (against population growth), but her advances are rebuffed. She sets off towards the interior of Festive to learn its innermost secrets.

Expanding on Aldiss’ argument in Non-Stop that “a community that cannot or will not realize how insignificant a part of the universe it occupies is not truly civilized,” Coney posits an unusual gender commentary throughout the tale in which men maintain a false illusion of reality. Women, increasingly possessed by primordial urges to repopulate the world, gravitate towards the upper reaches of Festive, closer to the supposedly radiation laden outside (125). Men, obsessed with stabilization and order, retreat to the bowels of the world, away from women, away from sexual temptation, away from the outside and all its supposed horrors. In their hellish interior they run amok, paranoid and possessed by an unknown animalistic urge, mowed down by the scythed agricultural machines that maintain vast hydroponic facilities.

But, as with all enclosed environment stories, there will be a conceptual breakthrough. And in Coney’s vision women will be responsible for it. And the heroine Jillie, with the wisdom and assistance of Jeremiah, will drag David, kicking and screaming desperate for the lower levels, along with her into a new world.

Recommended for the fascinating location of Festive and Coney’s reworking of gender roles. The narrative works but, unlike some of the more ingenious formulations of the generation ship idea that I have encountered in this series, “The Mind Prison” reads as a bare-bones distillation of the theme.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Reading your review brings to mind a comment Marx makes in the last section of Capital vol 1. Speaking of the Swan River colony in 19th century Western Australia (near modern day Perth) Marx tells how many of the colonists, on arriving, ended up abandoning the colony, and in some cases joining the local indigenous people. Marx mordantly quips that despite the colony’s leaders bringing all of the material necessities to establish the colony, they failed to bring the bourgeois social relation from England with them.

What i would like to see in a gen ship fable is precisely this: the crew refusing to live the life that they have been invited/forced to. In part Brunner tried to address this in his story Lung Fish. But in that it’s the younger generation growing away from the desires that founded the mission of their parents. How about instead a gen ship story in which the “degeneration” begins in the first gen, a few years out?

The gen ship remains endlessly fascinating to

me precisely because it is the world in microcosm—or the world as journey/passage. The assumption in most that i’ve read so far is similar to liberal social contract theory: the first gen agree to the mission, but this is later called into question. What would be more interesting to my mind would be to problematise this from the outset: the social contract is always a fable, usually propagated by the ruling classes to justify their rule.

Hmmm, thinking of which, isn’t this sort of the thrust of one of the Chad Oliver stories we read?

I have no idea why there aren’t stories from this era — to my knowledge — that explore problems that might crop up in the first generation involving a prescribed life. Perhaps as they are selected due to their vigorous adherence to the actual mission? It would be a danger to select a crewman who suggests the entire instituted system might be wrong. But then again, there are plenty of stories where major problems occur with the first generation of colonists on a planet (i.e. more like the Marx quip) who “go native” or choose completely different paths. Paul Atreides goes straight to the Fremen (haha) [just saw the Dune movie so I couldn’t help but reference it].

Maybe there are newer stories that explore that idea. Rich Horton keeps on adding (thank you Rich!) newer stories to my index. There does seem to be a resurgence in the interest in the genre. I’ll leave it to him — if he stops by — to point out newer stuff that might do that.

I think Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves does explore 1st-gen issues with the entire instituted system. Things go very bad, partly as a result of that.

Thanks for the suggestion. I’ve read a few of his novels but definitely his earlier ones — Snow Crash, The Diamond Age, Cryptonomicon, and a few others that have escaped me (maybe in the Baroque Cycle).

I’m not wholeheartedly recommending Seveneves, but it does explore technocrats, dismissal of communications/politics, and inclusion/exclusion based on perceived value, all of which would be highly relevant to generation ships. I liked his awareness in his early Zodiac of media strategies by big companies and scrappy environmentalists. I keep meaning to read some of his others (I read Snow Crash first).

Oh, no worries. I’ve long since moved on from Stephenson — he was very much an author of my early 20s (~2008) and I have no plan on returning to any newer SF (I enjoy SF the most if it’s connected to a historical era I enjoy, i.e. post-WWII-1980s).

I’m always happy to read about/listen to critics discussing newer SF so I can keep abreast of modern developments.

In my review of Robinson’s “The Oceans Are Wide” (1954) I used the heading “The Generation Ship As Laboratory of Authoritarian Desires”– I suspect there’s something in that idea. The enclosed space represents the perfect vehicle for authoritarian experiments that only crumble after multiple generations.

Robinson’s novella and later novel are probably the closest to the concern about the social contract that mythologically founds the community. The gen ship story is the perfect fictional setting for literally

manifesting this mythos and playing with it. Le Guin raises the question in part in The Birthday if the World, but following Brunner’s lead, with an emergent social form asserting itself through the original agreement/mission.

Do you mean Le Guin’s “Paradises Lost”? I think it’s in The Birthday of the World collection. I remember adoring that story when I read it before I started my site although all the details have faded from memory.

Yep. The dangers of trying to recall the title of a story that you read so long ago…

Haha, at least you remember something about the contents. I only remember the feeling I had after finishing it.

I remember liking it too!

I know I’ve mentioned this to you before, but i’d love to hear what you think of Molly Gloss’ “The Dazzle of Day” (1997). I realise it’s a bit “late” for you, but it is such a wonderfully rich example of the gen ship trope—and a fave of Le Guin’s too, apparently.

You know me…. I’m in my groove and don’t want to deviate for a bit at least.

Tempted by the Coney story? It has some flaws… I mentioned one below to Expendable.

I’m very tempted. I’ll read it and get back to you.

antyphayes: “How about instead a gen ship story in which the “degeneration” begins in the first gen, a few years out?”

‘Silhouette’ by Gene Wolfe, a novella from 1975, is arguably that story (though much of the ship’s population is kept in suspended animation and the story only defaults to a ‘Lungfish’-type generation-ship solution at the end).

Our host JB reviews it here —

https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2017/01/22/book-review-the-new-atlantis-and-other-novellas-of-science-fiction-ed-robert-silverberg-1975-le-guin-wolfe-tiptree-jr/

I’ll read the Coney story and report back.

I’m very curious about the Wolfe. Thanks for the heads up. Though I can hear Joachim words tapping away at me from within: “it’s a sleeper ship story, not a gen ship!”

The Wolfe story is a masterpiece!

Wonderful appreciative review, Dr. B. It sounds very Seventies to me, so I’ll be avoiding it llike it gots th cooties. Too soon after Marge Piercy smacked my teeth loose with the dreary missed opportunity of WOMAN ON THE EDGE OF TIME.

I saw your review and tried to comment but your site still doesn’t let me. I can comment on multiple other Blogger sites including one where I have to be a member like yours (I know we have discussed this at length).

While I have not read Woman on the Edge of Time yet, I can absolutely understand why someone might not like Dance the Eagle to Sleep due to how enmeshed with the 1970s it felt: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2020/05/26/book-review-dance-the-eagle-to-sleep-marge-piercy-1970/

The Coney story works as a reworking of the theme. The reason it’s not higher is due to Coney’s unfortunate tendency to create cringey scenarios where young women get aroused by/run after much older men. This appeared in Syzygy (1973) as well: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2019/11/10/short-book-reviews-rogue-moon-algis-budrys-1960-and-syzygy-michael-g-coney-1973/

I just finished it.

Coney’s use of a pop-psychoanalytic trope could have been more interesting than it is—or at least more interesting than his use of it. The idea of the people of Festive splitting between a more expressive and repressive sexuality as a result of the trauma of enclosure is a great idea. Sadly, he hangs it on a dull and reactionary conception of nature which, surprise surprise, renders woman more “natural” and sexually expressive, and men less so, and so on. The question that rose immediately for me is this: why was it necessary to have this split along gender lines? Why not have both men and women making up the population of both the expressive and repressive sides of the dilemma? It all ends up being so horridly heteronormative among other things—reinforced by Coney’s embarrassing descriptions of the women’s barely controllable need to fuck men.

Apart from this clunker I agree that there is some interesting stuff going on here.

What was confusing to me was the figure of Jeremiah — the split seems pretty aggressive on gender lines but for some reason he seems immune. The story could have presented it as a revolution steered by the elderly! Is he the only older person who remembers the past? Which would have been a hilarious twist on matters if the entire generation joins hands with the younger women in their quest for a new world and dragging the young men out of the darkness… I guess Jeremiah’s generation represents the moment where most knowledge of the past was completely lost.

I agree on all points of your comment — that is the reason I didn’t rate the story higher. While a commentary on Heinlein and company, he doesn’t do much with the commentary… other than the gender shift and the pop-psychology angle you indicate.

Jeremiah was definitely a wasted opportunity. He was by far the most interesting character. And where were all the other old people? A geriatric revolution would have been great. The scene where Jillie is overcome by rampant desire for Jeremiah is just silly, even if it’s sort of “explained” later by the sexual bifurcation.

I agree that he doesn’t do much with the implied commentary on Heinlein et al. I assume he goes into more detail in the introduction to his collected stories?

It might be time to check out the Wolfe, tho i feel obliged and maybe a little more motivated to have a look at the Arthur Sellings story.

Yeah, as I mentioned to Expendable, that ridiculous scene with “rampant desire” is a frequent problem in Coney’s SF. He often has scenes where younger women cannot withhold their sexual feelings for much older men that always comes off as extreme cringe — Syzygy (1973) is the absolutely worst in this regard.

I referenced all the main points of his “commentary” from the short introduction in this review. I can reproduce the entire mini-intro when I get home.

That would be great if you do, but don’t worry too much if you’ve already covered the points.

Hey, I finally got around to reading the Arthur Sellings short. I’ve added a few comments on your review page.

And now, thanks to having secured a copy of Gene Wolfe’s ‘Silhouette’, I’m off to read that!

Here is the full paragraph intro: “I cannot explain why I find the closed environment story so fascinating; why my earlier reading included frequent rereads of Aldiss’ Starship, Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky, and others of that breed. Why should an adventure story be more exciting, merely because the people therein are not subject to external influences? Is it the fun of speculating just how strange people can become, when they have no yardstick to judge their strangeness by? Because this is rather a cruel form of fun. I would think that these stories emphasize identification, since the hero is invariably the only normal person around, surrounded by nonsensical religions, illogical facts, widely held misconceptions, which only he can see the stupidity of–while all the time he himself is condemned as a heretic and a radical. Just like real life, don’t you think?”

Thanks for that.The first few sentences sounds like the basis of a research project. That seemingly inexplicable fascination has asserted itself over me too!

It’s hard not to read that paragraph’s use of he and himself and the presence of a female main character in the story as a direct reframing of what was standard. Which is why I saw it as a commentary — if indirect — on the generation ship stories that remained firmly in his mind.

I agree that it was a step forward to make one of the protagonists female, and attempt to address the society in a more rounded fashion. But he blows it! Maybe I shouldn’t be too harsh, but i feel that no one has progressed much from Aldiss. (at least on true basis of the many stories we’ve read).

However, what would constitute “progress”? Perhaps the only way to go now is a commentary on the gen ship trope. It’s novelty is tapped out.

I started the Wolfe last night but haven’t finished it yet.

Omg, I wish I had this novel! Purple Plague: A Tale of Love and Revolution (1935)

It’s sort of an enclosed environment — a ship adrift due to years due to a plague. And an egalitarian society is created. So, like a generation ship, it has a rigorous hierarchy and its overthrown in the first generation. I don’t know if its organized around “generations” or if children are even born on board.

It was written by a socialist politician in England — Fenner Brockway (1888-1988). SF encyclopedia entry: https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/brockway_fenner

Intriguing. He’s life seems interesting too, though he had much too faith in the parliamentary system for my taste. Not to mention his peerage!

Your mention of this has dislodged a dim memory from childhood of a TV movie about a closed community called “Goliath Awaits” (1981). It’s set in the then present day after some people discover that a ship sunken in the Second World War has somehow managed to survive and thrive on the bottom of the ocean…

I loved it as a 13/14 year old but i’m not sure if i’d stand by that judgment.

Sounds like Goliath Awaits is riffing off of one of the storylines in James White’s The Watch Below (1966) https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2011/12/10/book-review-the-watch-below-james-white-1966/

I thought that as I was writing it up. Probably nowhere near as good tho!

I’m a fan of the Michael Coney work I’ve read, particularly the beautiful HELLO SUMMER, GOODBYE, but I haven’t read this one. Perhaps whe I have time …

This is far from his best and operates more as a commentary on the subgenre of gen ship stories than as a story itself — which is why I had to include it in this series!

I’m an intermittant fan of Coney.

Hello Summer, Goodbye is brilliant: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2013/11/12/book-review-hello-summer-goodbye-variant-title-rax-michael-g-coney-1975/

As is “Those Good Old Days of Liquid Fuel” (1977): https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2019/08/11/book-review-the-1977-annual-worlds-best-sf-ed-arthur-w-saha-and-donald-a-wollheim-1977/

But I’ve disliked a bunch of his work as well — notably Syzygy (1973)