Today I’ve reviewed the twenty-sixth and twenty-seventh story in my series on the science fictional media landscape of the future. In Kate Wilhelm’s masterpiece of blue-collar drama “Ladies and Gentlemen, This Is Your Crisis” (1976), reality TV serves both as domestic irritant and therapy. Langdon Jones, in “The Empathy Machine” (1965), also speculates on the therapeutic aspects of “viewing” the crisis of another in a media-drenched future.

As always, if you know of other stories connected to this series that I haven’t reviewed, then let me know in the comments!

Previously: Richard Matheson’s “Through Channels” (1951) and Robert F. Young’s “Audience Reaction” (1954)

Up Next: Henry Kuttner’s “Year Day” (1953)

David Plourde’s cover art detail for the 1978 edition of Best Science Fiction Stories of the Year: Sixth Annual Collection, ed. Gardner Dozois (1977)

5/5 (Masterpiece)

Kate Wilhelm’s “Ladies and Gentlemen, This Is Your Crisis” first appeared in Orbit 18, ed. Damon Knight (1976). You can read it online here if you have an Internet Archive account. I read it in her collection Somerset Dreams and Other Fictions (1979).

Lottie comes home from the factory Friday afternoon with “frozen dinners, bread, sandwich meats, beer” to prepare for the weekend watching reality TV with her husband Butcher (121). As predicted, Butcher comes home mad, “mad at his boss because the warehouse didn’t close down early, mad at traffic, mad at everything” (123). He pulls up his recliner–they’ll sleep in front of the softly flickering screens–Lottie microwaves the dinners and brings her husband beer. The ritual commences.

The show, This Is Your Crisis, plays every hour of the weekend in their house on a portable TV and their new expensive wall unit–required for the full experience. The premise? Survival in Alaska! Get to the extraction point first and win one million dollars, after taxes. The contestants? All dissatisfied folk driven to crime undergoing “Crisis Therapy that would enrich their lives beyond measure” (125). A special satellite and sensors relay their every move live without breaks or interruption in the feed. Lottie and Butcher sleep when they sleep. And when they wake up in the middle of the night, they listen to the calm voice of the night commentator, and watch the colored dots blink on the map, and watch the contestant campfires flicker safe in their own home.

The metaphor is simple. Lottie and Butcher, trapped in their lives, imagine they would win the show: “week after week it was the same. They forgot the little things and lost” (131). They project their own desires and insecurities onto the contestants. They are consumed by the show. Butcher doesn’t move from his recliner. They don’t change their clothes or bathe. Butcher screams at his wife when she tries to get him to clean up the beer cans. He responds violently when she gloats over the misfortunes of his chosen contestant. And when another contestant wins, she “slipped her arm about [Butcher’s] waist” and put aside the sad desperation of the weekend (135). The show is therapy for the viewers. And the next week, and the next, and the next.

While reading “Ladies and Gentlemen, This Is Your Crisis” it’s easy to forget that An American Family, the show credited with “birthing the reality TV genre,” only aired three years earlier in 1973. Two “precursor” reality TV-esque shows appeared before An American Family. Candid Camera, first a radio program that premiered in 1947, hit American televisions in 1948. And in late January 1965, The American Sportsman followed celebrity guests on hunting and fishing adventures. All of this is to say that Wilhelm’s survivalist reality TV, as with hyperviolent formulations in Robert Sheckley’s “The Prize of Peril” (1958) and Walter F. Moudy’s “The Survivor” (1965), do not have clear predecessors. The first adventure “survivalist” take, Eco-Challenge, didn’t air until 1989! Consult this list for the eleven earliest reality TV shows.

I highly recommend “Ladies and Gentlemen, This Is Your Crisis” for fans of kitchen sink realism-style science fiction that explores how societal transformation impacts blue-collar lives. Wilhelm imagines an immersive viewing experience quite similar to multi-panel/camera Twitch livestreams. Beyond its ideas, the story is stark, rigorously structured, and adeptly told. Readers who might be put off by Wilhelm’s more oblique New Wave masterpieces–“The Planners” (1968), “The Encounter” (1970), and “Windsong” (1968) come to mind–might enjoy the minimalism of this one. Will be in my top 5 short story reads of the year and might even challenge “Baby, You Were Great” (1967) as my favorite Kate Wilhelm vision.

Reviews of Other Worthwhile Reality TV Short Stories

Brian W. Aldiss’ “Panel Game” (1955)

Robert Sheckley’s “The Prize of Peril” (1958)

Damon Knight’s “You’re Another” (1960)

Walter F. Moudy’s “The Survivor” (1965)

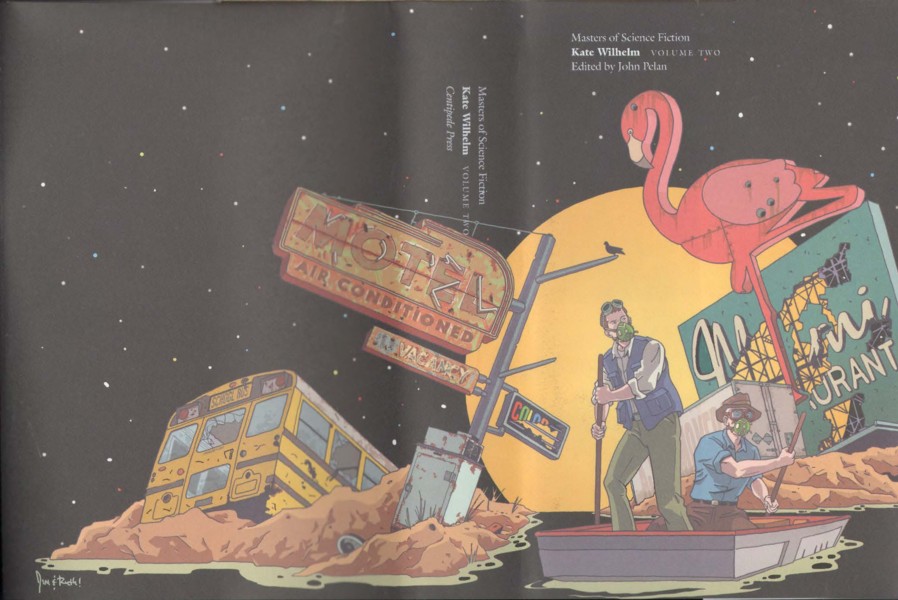

Jim and Ruth Keegan’s cover for Masters of Science Fiction: Kate Wilhelm, Volume 2 (2020)

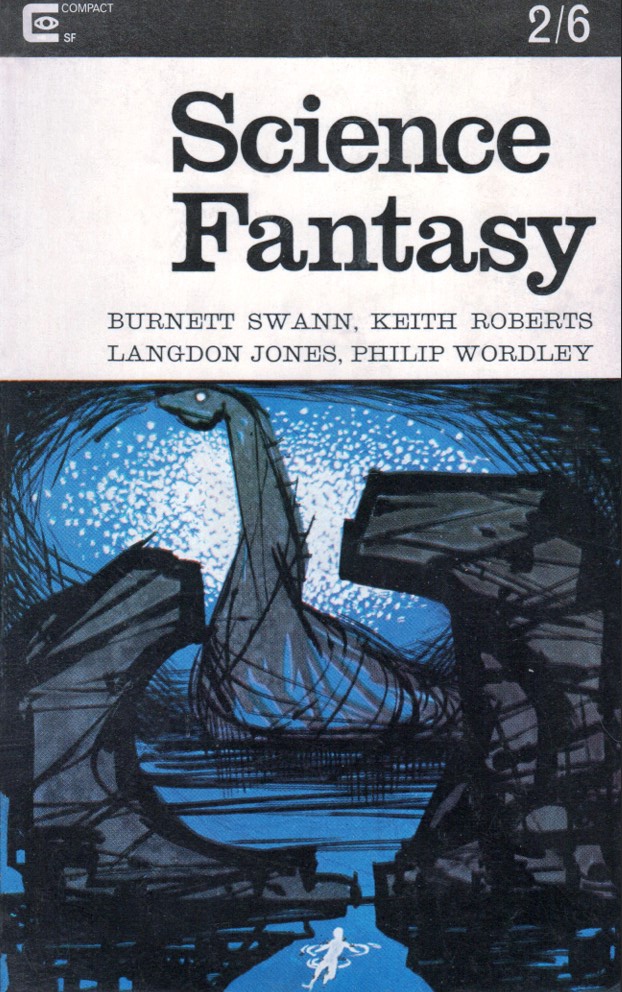

Keith Roberts’ cover for Science Fantasy, ed. Kyril Bonfiglioli (January-February 1965)

3/5 (Average)

Langdon Jones’ “The Empathy Machine” (1965) first appeared in Science Fantasy, ed. Kyril Bonfiglioli (January-February 1965). You can read it online here.

Langdon Jones (1942-2021) is a lesser known luminary of the New Wave movement. He contributed a spectacular sequence of stories between 1964 and 1972 and helped edit Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds. Jones also edited an influential anthology, The New SF: An Original Anthology of Modern Speculative Fiction (1969), that I need to acquire. “The Empathy Machine” is a strange beast that is far from his best. Like Wilhelm’s tale, the story starts as a futuristic drama of a seemingly irreparable relationship in a puritanical, advertising-drenched, and overpopulated future. However, it quickly changes tack and morphs into an exotic exploration of the Martian landscape and secret Martian technology. The threads intertwine in a less than satisfying manner.

The first section creates a dystopian media landscape saturated by invasive advertising in even the most personal spaces. Henry Ronson’s bathroom mirror periodically shifts into commercials: “A softly seductive face filled the mirror. ‘Are you a–man?’ the girl whispered. She gave a soft little moue, which somehow gave the impression of strange hungers, and strange mixtures of desire and satiation. ‘Then you shave with Shavicream” (16). Ronson is something of a holdover from a previous era and detests their presence in his life and his wife’s enjoyment of them. He detests everything about his wife: her capacity for crying “often and easily” (18), her frigidity (27), her plumpness (26), her lack of fight, and speculates that she married him only for a larger apartment, and might conspiring to force him to commit suicide (23). He resolves to kill her on a vacation to Mars.

The second portion of the story follows their adventures on the Martian surface. They discover ruins in the sands. And a strange piece of technology that allows Ronson to “view” his wife… he is the reason for her suffering.

I found that the separate parts do not mesh effectively. The story contains too many threads and its best to not think to much about the illogical premise of the Martian portion of the story. Is Ronson’s cruelty directly caused by the media-saturated world? What elevates “The Empathy Machine” above more banal dystopias of this ilk is Jones’ ultimate argument that technology–in this instance, the mysterious Martian machine that allows Ronson to “see” Marian’s trauma—can be used to create the space for healing a relationship and empathy. This is a refreshing perspective. Regardless, I’m probably overrating this one. I am remined of John Brunner’s far superior “Fair” (1956).

For superior Langdon Jones works, check out my reviews of “I Remember, Anita…” (1964) and the collection The Eye of the Lens (1972).

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

For your media series, do you know Charles V. de Vet’s “Special Feature”? ASTOUNDING May 1958 and in Conklin’s pb original anthology SEVEN COME INFINITY. There’s also an expansion to novel length that adds nothing but bloat and should be avoided. It’s similar to “The Prize of Peril” except that the guest of honor is a shipwrecked extraterrestrial. Crude but effective, I thought.

Yes, you’ve recommended it (or Rich?) in the past! My list is massive so I’m not making the best time through the backlog and I apologize for not getting to your suggestion faster. Alas.

Thank you for reminding me about the de Vet. I haven’t read any of his work.

Have you read the Wilhelm story? I described it on Twitter as a “grail” story of sorts for me — the conjuration of what I tend to enjoy told in a powerful way.

Yes, but not recently, an omission I should remedy.

She’s a favorite of mine. I hope to review the rest of the Somerset Dreams and Other Stories collection that “Ladies and Gentlemen” appeared in. I have another story of hers from the same collection lined up for my series on series searching for SF short stories that are critical in some capacity of space agencies, astronauts, and the culture which produced them.

So I dug out my own copy of SOMERSET DREAMS and reread “Ladies and Gentlemen,” and didn’t think quite as much of it as you did. It’s very well turned but to my taste a little overbearing in its grimness. Having exhumed the book, I read another of the stories, “The Encounter,” which I remembered only vaguely, and was more impressed: creepy, cryptic, beautifully controlled.

As my old blog friend Megan AM (who unfortunately deleted her wonderful site) once said, Joachim Boaz likes his SF ” “moody, broody, meta, and twisted.” So I’m all okay with the griminess. I also found “Ladies and Gentlemen” beautifully controlled.

I have plans to read the rest of the collection. I read “Planet Story” (1975) recently in Somerset Dreams and will include it in my search for the depressed astronaut/critical accounts of space travel series.

Yup, I also loved “The Encounter.” I linked my earlier review above.

That Dozois Best of cover looks so familiar, yet I am sure I never had a copy…

Maybe you saw another one of his covers! I think it’s quite effective.

Read the Wilhelm?

I have not.

I assume you’ll get to that Orbit anthology eventually. I’ll keep an eye out for it!

I read the whole run of Orbit so I would like to amend my answer to “Yes, but I forgot that I had.”

Ah. That’s a shame. Must not have had any staying power for you…. alas. haha.

I must confess, I can’t completely tell what you thought of it: “A troubled couple find meaning in reality shows.”

I assume the title of the review means you grouped it in with the “But I Don’t Care” and “diminishing-returns territory” category. That said, “Still, the Wilhelm would be as timely now as it was in 1976” seems to suggest it was the best of the anthology!

The combination of how much I read and multiple sources of brain injury mean sometimes I need prompts to remember stuff. Orbit 18…

I thought Orbit in general hit diminishing returns after, oh, lets say 9. Towards the end of that project, I was really regretting setting it up without an escape hatch. The Wilhelm was an exception to that general trend but it didn’t help that I read it in what was becoming an endurance test.

I must confess, that Orbit 18 anthology has a ton of authors I normally love — Craig Strete (and his bitter misanthropic–justified–sarcasm and satire), John Varley, George R. R. Martin, Wilhelm, and Lafferty (does the Lafferty fit my series? You mention a PR cabal. Is it media related).

The Lafferty is media-related, very much so.

“The Hand with One Hundred Fingers was pretty much in control of things then. It enhanced persons and personalities, or it degraded them, for money, for whim, or for hidden reasons. And what it did to them was done effectively everywhere and forever.”

On to the list it goes! Thank you!