In January, I inaugurated a new review series on the urban landscape in science fiction. I finally present the second post! And it’s a good one. I am joined by Anthony Hayes, a frequent contributor and creator of wonderful conversations over the last few years on the site (as antyphayes). I recommend you check out his website The Sinister Science. In addition to ruminations on science fiction–often through the lens of his academic PhD research in the Situationist International, “as well as other related left-communist and post-situationist writings,” he creates fascinating collages that interweave comic books, textual play, and historical images.

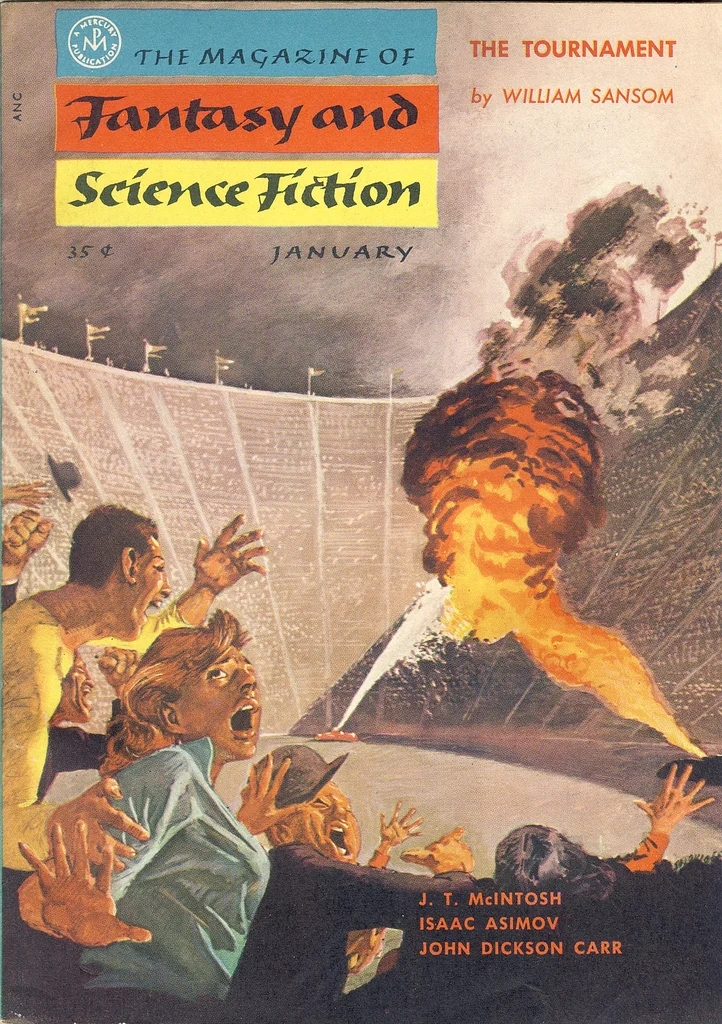

We chose Robert Abernathy’s deceptively complex parable of urban alienation “Single Combat” (1955) as our inaugural story. It first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Anthony Boucher (January 1955). You can read it online here.

Previously: Michael Bishop’s “The Windows in Dante’s Hell” (1973), Barrington J. Bayley’s “Exit from City 5” (1971), and A. J. Deutsch’s “A Subway Named Mobius” (1950).

Up Next: TBD

Nick Solovioff’s cover for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ed. Anthony Boucher (January 1955)

Anthony Paul Hayes’ Rumination

Urban alienation writ large: Robert Abernathy’s “Single Combat”’ (1955)

Having planted an explosive device in a forgotten corner of an unnamed, North American city, the similarly unnamed protagonist flees. However, in fleeing the protagonist comes to realise what they had hitherto only suspected: that the city has become a living, conscious thing, and like all such things is willing to fight for its survival.my

Robert Abernathy’s “Single Combat” is a compact and claustrophobic rendition of modern urban alienation. The asymmetry of the protagonist’s struggle–a lonely man engaged in single combat with a city–ably expresses an experience familiar to any city dweller overwhelmed by the sheer fact and mass of the urban jungle.

Over the course of the story the protagonist moves from imagining the city is a conscious organism to knowing that it is. But is this dawning knowledge or simply the fever dream of a paranoiac? Every obstacle that he faces–unforgiving traffic, runaway trucks, the hellish abyss of the subway, advertising hoardings come loose, building cornices falling unbidden–could simply be the mundane dangers of the city, rather than the murderous intent of a town literally awoken to self-consciousness. When the protagonist finally speculates in a science fictional fashion upon the nature of the city’s consciousness and volition, it is never clear whether this is the actual truth of the matter or simply the increasingly paranoid speculation of a terrorist desperately trying not to be blown up.

Recalling his former life, the protagonist, “hate, growing always,” comes to see nothing but the despair and concrete misery of urban life, “the ugliness that for so long had seeped into his soul and almost destroyed him” (12).1 Indeed, his experience of the city is purely negative, seemingly beyond any hope of redemption or diversion from its present chaotic growth and development. Consequently, the protagonist becomes a misanthrope, seeing in his fellow city dwellers mere “corpuscles” of the urban behemoth.

Even though the protagonist gains “a new, ironic detachment” (12) upon freeing himself from being in thrall to this urban existence, he is driven only to the thought of destroying the city rather than escaping or attempting to reconfigure it. And so he becomes ripe for manipulation by the mysterious “they” (15) who make him “the city’s executioner” (15). Indeed, his detachment seems to be anything but, as he single-mindedly focuses upon destroying the city. The real irony of his plight being that the city only truly devours him once he turns utterly against it.

Uncredited cover for the 1970 edition of Cities of Wonder, ed. Damon Knight (1966)

Abernathy’s place in the universe; or, a speculative theory of speculative fiction

Abernathy’s story is a marvelously vicious example of seeing the modern city for what it is–a dystopia–driving home not just the horror and despair of urban life, but even more so the futility of trying to put an end to it. The city as a force beyond the control of its atomised denizens is ably evoked. Indeed, in the protagonist’s coruscating assessment and the story’s bleak dénouement we can recognise an anticipation of sorts of the New Wave in SF of the 1960s.

Yet the dystopian city in SF has longer roots than the emergent taste for this trope from the 1960s and on. We can find it in The Time Machine (1894/5), for instance. Closer to Abernathy, it can be found in Clifford Simak’s City (1952), with his beguiling mashup of cybernetics and bucolic life served with a side of distaste for the modern metropolis.

But it is not until the 1960s, alongside of the New Wave in SF, that the dystopian city truly flourishes as an idea and focus within SF. J. G. Ballard showed the way in stories like “Build Up” (variant title: “The Concentration City”’” (1957), “Chronopolis”’” (1960), “Billennium”’” (1961), and “The Subliminal Man” (1963)–to name but a few of his many works. A recurrent theme in Ballard’s works is not just the city as the exteriorisation of the psychopathologies of its denizens, but even more the city as the materialised orchestration of such. It is not so much that man [sic] makes the city but rather it is the city that makes the man sick. Abernathy’s “Single Combat” not only resonates with Ballard’s psychologistic reading of the city but precedes his more obsessive urban focus by a few years.

However, most important of all for the turn to the city as subject of dystopian speculation was the lived reality of cities like New York, London, Paris, Tokyo and Mexico City in the 1960s and 70s. In the three decades after the Second World War, the “problem” of the city, particularly their rapid growth and concerns about “overpopulation”, came to dominate a fair amount of critical discourse on urbanism. Like Ballard’s later work, Abernathy’s fictional vision of an unconstrained and out of control urban blight bears comparison with the urban crisis identified by contemporary urban critics like Jane Jacobs, Lewis Mumford, and Henri Lefebvre.2 Indeed, Lefebvre noted in a 1970 work that SF had already anticipated or sketched most possible future scenarios for the city—though he should have added, with a large helping of gloom.3 Nonetheless, alongside the New Wave’s broadening of science fictional sensibilities came an often-reductive conception of the SF that preceded it. Advocates for and representatives of the New Wave imagined themselves as dragging the unwilling genre of SF kicking and screaming into the adult world of sophisticated and complex literature, in opposition to the naively optimistic and infantile works that had hitherto dominated.

With an eye to the subject matter at hand, a good example of the New Wave’s often reductive attitude to its predecessors can be found in a work of an author profoundly influenced by the New Wave. In William Gibson’s short story, “The Gernsback Continuum” (1981), a Golden Age pulp city of the future shimmers in the distance only to fade like the bad dream it always was. Gibson’s contention that the ‘perfect’ city of the future was only ever a bad dream of the 1930s and 40s, is itself a variation of the argument made by J. G. Ballard, among others, in the 1960s: that the “future” posed in SF is a product of the desires and anxieties of the present in which it is composed. However, the contrast between the purported utopian “perfection” of the pulp imaginary with the latter cynical dystopian “realism” of Ballard and after is not always easy to reconcile with the facts.

Consider the decidedly pre- and anti-New Wave author, John W. Campbell, and his short story “Twilight” (1934) (as by Don A Stuart). What at first seems the perfect Gernsbackian city of impossible spires and mechanical perfection per Gibson’s description reveals itself to be something more–and less–remarkable. Campbell presents its perfection as a moment of the defeat of future humanity, having robbed them of curiosity by way of the city’s vast and perfected automation. Campbell’s vision is sort of like Wells’s, without the Morlocks, and so, somewhat less narratively interesting. Wells’ vision is more politically charged, insofar as the future decadence of humanity is attributed to the class antagonism of Wells’s 1890s, whereas Campbell fashions a melancholic vision from the apparent success of his fictional utopia.

I would suggest that the city as a figure of action and speculation has always been a problematic object in SF. Certainly, the perfectibility of the city is raised in early SF, and here SF shows its inheritance and lineage–particularly that of the utopian speculations of the 19th century. However, it is far from clear to me that such perfectibility was the only presentation of the city or even the dominant one prior to the rise of the more self-consciously dystopian and ironic SF promulgated from the 1960s and onward.

Notes

- Page references are to the Damon Knight edited anthology, Cities of Wonder (Macfadden-Bartell, 1967).

- See, for instance, Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), Mumford, The City in History (1961), Lefebvre, The Urban Revolution (1970).

- See, Henri Lefebvre, The Urban Revolution, trans. Robert Bononno, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003 [1970], pp. 113-14.

Jack Faragasso’s cover for the 1967 edition of Cities of Wonder, ed. Damon Knight (1966)

Joachim Boaz’s Rumination

4.5/5 (Very Good)

A nameless man, in a nameless city, plants a bomb in a basement. The city, cloaked with a heady dystopian gloom of racial violence and pollution, attempts to prevent his desperate escape. It’s a labyrinthine gestalt in which all its component parts–denizens, machines, symbology, and physical decay–become agents of its primal desire to survive.

The Conceptual Framework

According to Rolf Lindner in “The Gestalt of the Urban Imaginary” (2006), the city is a “culturally coded space, soaked in history, which becomes a place of the imagination, a symbolic place filled with meaning.” We experience the overlap between the actual and imaginary via “accompanying images and symbols” inscribed upon and embedded within the urban landscape.1 Rather than the imaginary as a “flight from reality,” the imaginary, according to Pierre Sansot, serves as another way of connecting to it.2 The imaginary gives the place meaning, it “lends it a spirit.”3 The idea of the gestalt posits that breaking down a whole into its component parts is “mechanical and inevitably misleading.”4 Instead, to understand the urban experience we must map its texture, “the allegories, anecdotes and legends,” the specificity of the place.5 The city fills its “narrative spaces” with “particular (hi)stories, myths and parables.”6

Robert Abernathy’s “Single Combat” (1955) traces a singular narrative thread, interwoven within the gestalt texture of the urban imaginary, that simultaneously typifies and mythologizes the forces of urban alienation. It is a thread that cannot be understood alone. The singular interweaves and melds with the whole.7

An Encyclopedic Glimpse of Urban Pattern

Beset on all sides by anamorphic traffic that “surged, snarled, panted” (64), the nameless main character in “Single Combat” remembers joining the organization that set him on his path to destroy the city: “he’d done their bidding, dutifully learned their slogans that were loud and meaningless as a child’s rattle” (64). He knew their purpose–“to make him the city’s executioner” (65). But what is the nature of the beast?

History: Abernathy’s conjuration of the urban gestalt reads as a distillation of 1950s societal ills and environmental devastation afflicting the northern industrial landscape.8 In the 1940s and 1950s, black migration to northern cities for economic opportunities and flight from the Jim Crow South triggered racial violence, the creation of segregated ghettos, and white flight to the suburbs.9 The empty promises and violence literally permeate the air.

He breathes in the city’s polluted fumes, air “that was rank with memory” (63). The memories that flood over him include the vitriol–“the raucous voices, the jeers, the blows, the brutality of life trapped in a steel and cement jungle”– and threats of violence aimed at Italian immigrants, Jews, and black Americans (63). In another instance, he remembers the empty facade of the American Dream: “You’re late, there’s no jobs left. Move along” (63). Do these historical fragments reveal the main character’s radicalization? Are these even his story? Does it make a difference? The part cannot be separated from the whole. The alienated cannot be differentiated from the mass.

Symbols: As he flees across the city, he engages in a dialogue with the symbols that surround him. He notices a “pint whisky bottle” placed “upright with meaningless care by whoever had drained and left it” (62). It is but one sign of the “ugliness that for so long had seeped into his soul and almost destroyed him” (62). He interprets the cluster of nameless souls that gather “under the multitude of colored signs that glowed and blinked” of restaurants and bars as a manifestation of the self-deluding narrative that tomorrow will be better, “they were weary and eager to believe” (65). In another moment he analogizes the city as the Biblical Leviathan, “proliferating, thrusting tentacles far up the valley” while “eating deeper and deeper into the earth” (68).10 There’s the inundating feel of exegetical anxiety as the symbols entropically gather, hemming him in on all sides.

Narrative Patterns: His flight takes the form of a heroic quest. He is beset on all sides by the city, “evolved from an invertebrate enormity of wild growth to a high creature having the tangible attributes” of “will and purpose and consciousness,” attempting to destroy him (68). The city animates its entire system to stand in his way. The city sacrifices its parts. A trolley crashes towards him, “the broken end […] like a great snake striking, hissing and spewing blue flame” (66). Trucks skid. Sidewalks buckle. Cornices fall. The city was merciless.

Returning to the city as a location that overlaps the actual and imaginary: Abernathy’s “Single Combat” intellectually and narratively succeeds in weaving a parable of urban alienation in part because he includes just enough place-specific historical texture to anchor the reader in a distinctly American locale. In concert with the protagonist’s growing terror, we begin to perceive the city as an exposed latticework of signs–each contributing to a growing unease. The protagonist becomes both literally and figuratively enmeshed within the behemoth. He cannot escape. He becomes the archetypal urban legend of the man who tried to resist.

Highly recommended. I look forward to reading more of Abernathy’s fiction. I have his post-apocalyptic “Heirs Apparent” (1954) on my list. Any other suggestions?

Notes

- Rolf Lindner’s “The Gestalt of the Urban Imaginary” in European Studies, no. 23 (2006), 35. I used this article as the conceptual jumping off point of this ruminations. ↩︎

- Pierre Sansot, “L’imaginaire: la capacité d’outrepasser le sensible” in Sociétés 42. (1993), 411-17. Cited in Lindner, 36. ↩︎

- Bernard Cherubini, “L’ambiance urbaine: un défi pour l’écriture ethnographique” in Journal des anthropologues no. 61-62 (1995), 79-87. Cited in Lidner, 36. ↩︎

- Lidner, 37. ↩︎

- Lindner, 38, drawing on Gerald D. Suttles, “The Cumulative Texture of Local Urban Culture” in American Journal of Sociology col. 90 (1984), 283-304. ↩︎

- Lindner, 41. ↩︎

- I am reminded of the city of Ersilia in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1972), in which the inhabitants trace their movements coded thread. And when the cities move, encyclopedic glimpses of the urban pattern populate the plain. ↩︎

- For the general effects of suburbanization, check out Ch. 2 of Robert A. Beauregard’s When America Became Suburban (2006), 19-39: “The growth of the suburbs was inseparable from the decline of the large, industrial cities” (37). ↩︎

- See Leah Boustan’s good summary in “The Culprits Behind White Flight” in The New York Times (May 15, 2017). ↩︎

- Also, I assume, a reference to Hobbes. ↩︎

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Hi there! Did you read “Dumb Waiter”, by Walter Miller Jr.? The Abermathy’s story reminded me that nouvelle. Yo can read it in Astounding Science Fiction, April 1952.

regards

Yes! It’s a good one. My review: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2013/09/30/book-review-the-view-from-the-stars-walter-m-miller-jr-1965/

My complete review of index can be found here: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/science-fiction-book-reviews-by-author/

What did you think of the Abernathy?

I love ‘Dumb Waiter’. It kept coming mind when thinking about the Abernathy piece, though unlike the more fantastical and socially charged ‘Single Combat’, Miller’s story is more straightforwardly SF.

Other than my short review, my memories are vague at best. I should give it a reread!

“Street Talk” by J. B. Allen (1986) has a person learning how to communicate with the gestalt of a city https://scifi.stackexchange.com/questions/7914/story-where-scientist-communicates-with-cities-directly – it doesn’t go well for him

Sounds interesting! I wonder if Allen’s riffing off of John Shirley’s City Come A-Walkin’ (1980) in which the city becomes a person. https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2020/06/28/book-review-city-come-a-walkin-john-shirley-1980/

From the Shirley: “It’s the gestalt of the whole place, this whole fuckin’ city, rolled up in one man. Sometimes the world takes the shape of gods and those gods take the form of men. Sometimes. This time. That’s a whole city, that man” (18).

Tempted to read the Abernathy? Or have you already?

Strongly tempted. I’ll see where I can find it.

I made sure to link an online copy at the beginning of the post. That said, if you want a paper copy, the various editions of the Damon Knight-edited Cities of Wonder anthology is the best bet. It has many more goodies as well.

Thanks. Got the link now – don’t know how I missed seeing it before.

No worries! When you get to it, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Finally read it. I liked how the city was described as a living thing – complete with the teeth-like crush of the wall that fell on the protagonist. I think “You’re late, there’s no jobs left. Move along” is meant to evoke the Great Depression era. Abernathy has the city’s nature as a living thing as more of a fantasy element than as an SF one – or at least to me, it’s not clear how the attacks by the city work as SF. A more modern version would have a distributed computer intelligence causing some of the incidents that befell the protagonist.

Abernathy gives a *sort of* science fictional explanation for the city become gestalt, writing of how it grew over the centuries. But sure, there is no attempt at a *scientific* explanation. I realise this is where many SF types like to draw a line in the sand between SF and fantasy, but to be honest I find that most SF is fantastical, nonetheless. I don’t think this is necessarily a failing of the *science* of some SF, but rather the near impossible boundary conditions of a genre that purports to be “realistic” in its fantastical evocations of a time and place that do not take place–i.e., they are, at heart, fantasies.

You write that a “ore modern version would have a distributed computer intelligence causing some of the incidents that befell the protagonist”. Interestingly, a story by Walter Miller, ‘Dumb Waiter’ (1952), published 3 years before Abernathy’s story, has this precise set-up. And it’s a great story too!

Hello Andrew (and Anthony): I echo what Anthony said. I’m not bothered in the slightest by a lack of a “scientific” explanation. This story, in my view, succeeds because Abernathy explores that overlap and interaction between the “imaginary” and the “real” overlap in such an effective manner. One interpretation, as Anthony explains his his review, is that the entire experience might be more a delusion than reality. And that confusion is a perfect example of the fascinating overlap and interrelationships between the “real” and “imaginary” territories of a city that my review explores (through the lens of the gestalt).

Pingback: Robert Abernathy’s “Single Combat” (1955) | the sinister science

I’m not bothered by the lack of scientific explanation either (and I agree that Abernathy left it ambiguous as to whether the main character was sane and correct, or simply deluded). I just thought it was notable that a writer today would have the ability (if he chose) to explain a living city in a straightforward way (which would lose some of the ambiguity, probably). Now I’m reminded of “The Tissue Culture King” – the 1926 story that introduced “aluminum foil hats” to the world.

It’s more on the fantastical side of things as well in John Shirley’s City Come a-Walkin’ (1980). Although, Shirley frequently eschews “scientific” explanations despite future locales.

I’ve never heard of “The Tissue Culture King.”

Monteleone’s The Time-Swept City (1977) features a sentient city (Chicago) in a long durée environment. I’m not sure what explanation he gives. Unfortunately, Monteleone’s been in the news for all the wrong things (racism) else I’d be more tempted to read it.

Tissue Culture King is available here https://www.revolutionsf.com/fiction/tissue/

Thank you!