(Catherine Huerta’s cover for the 1st edition)

4/5 (Good)

“It’s the gestalt of the whole place, this whole fuckin’ city, rolled up in one man. Sometimes the world takes the shape of gods and those gods take the form of men. Sometimes. This time. That’s a whole city, that man” (18).

John Shirley’s City Come A-Walkin’ (1980), an early cyberpunk novel, succeeds as a surreal and earthy paean to diverse urban community and punk rebellion. A club owner and angst rocker join forces with a physical manifestation of San Francisco to fight the forces of technological change. While a brilliant evocation of aesthetic and emotion with sympathetic main characters, Shirley struggles to pull the reader in to the mechanisms of the hackneyed political corruption plot.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis

The year is 1991. San Francisco, a violent landscape of urban decay/vibrancy, approaches a technological juncture. The City itself, made human at night, a gestalt of its inhabitants’ fears and desires, fights against the forces of transformation. Cole and Catz find themselves inexorably drawn into a violent confrontation between the entities that control the streets.

Stuart (Stu) Cole, a college-educated ex-prostitute and failed political agitator, owns the Club Anesthesia, rated by San Francisco’s Chronicle “zero percent if you’re looking for an aesthetic and human atmosphere, 100 percent if you’re looking for endless noise, fistfights, eccentrics, hookers, and muggings” (9). It’s a bar to “dampen down […] pain” furnished with vandalized decorations, “patient progress charts on the walls,” and resembling a hospital ward (25).

Cole feels at home in the city with the denizens of the streets, wandering the multi-ethnic zones, taking photos with his Nikon of the cityscape, visiting the vibrant gay community…. I would argue that the novel comes off as remarkably gay-positive and accepting for science fiction of the late 70s/early 80s. Cole describes the gay neighborhoods as “overflowing with laughter and affection” (71). He enjoys the “sense of communality in their caresses […] and their joyful rebellion” (71). The majority of the people in 1991 still disapprove of them, “especially the neopuritanical movement” (71). Cole, on the other hand, celebrates their company and love. Shirley’s account of future San Francisco extrapolates from the vibrant Castro area gay scene (the arena of Harvey Milk) and the prominent lesbian neighborhoods of the Mission District in the 70s.

Cole’s friend (and eventual lover) Catz Wailen performs her brand of improvised angst rock from the club’s stage, her body contorted in “a hundred permutations of the moth’s last spasm as it burns in candleflame” (15). Catz, able to “see beyond” the translucent nature of the world (118), appreciates Stu’s willingness to take a risk on her radical music. She is far less susceptible to message of the city’s manifestation, that emanates a mechanical disco beat, when he walks into Cole’s bar…

Catz proclaims “That’s a whole city, that man” (18). The atavistic City draws his power from the sleeping and those “watching TV” (156). With Catz and Cole in tow, he ingratiates himself as a mediator, reconciling lost souls with their parents, attacking the corrupt gangs that threaten the urban reality. The City, able to enter human bodies and appear spectral through view screens, wages a war against the political forces bent on undermining the dynamic interlaced organism of relationships and communities.

As a “matrix of ideas, concepts pressed into concrete and asphalt,” The City embodies the whims and fears of its people. And Cole, as he instinctively understands […] “the secret geometries of the city,” allows himself to be its agent (81). Cole rationalizes the violence he commits (with the City’s instigation). Catz, on the other hand, sees through the paranoid manifestation of fear of change, and draws her motivation from her respect for Cole—or at least, until his ability to act as an individual is taken away.

Final Thoughts

Shirley conjures INTENSITY and MOOD with ease. The extended concert sequence—a band costumed as “gnostic holy men, initiate magicians, and alchemists” (84) masochistically moving “in bizarre choreography” in an “invocatory urban voodoo rite” (84)—is gorgeously wrought. We gaze with the mesmerized audience at the hologram of “a naval destroyer” sized beast with its “mouth opening to reveal the bars of a city jail from which prisoners peered with hollow eyes” (85).

Shirley’s love letter to the seedy underside of San Francisco of the 70s doubles as a moderately complex analysis of the urban environment.

“[San Francisco] is a unique city in some ways because it’s so compressed. I mean, it’s all crowded—the main part of it—onto this little peninsula, and up and down these steep hills. That means that the Latin communities and the black communities and the Filipinos and the Chinese and the Japanese and the gays, gays everywhere, and the Arabs and East Indians and the middle class whites—they’re all rubbing shoulders all the time, their various ‘ghettos’ overlapping. So there’s a strong feeling of community, I think” (25).

Shirley argues that the crowded and dirty environment of the cityscape allows vibrant communities to form and express themselves freely. This is unusual for the era. For example, in John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar (1968), from a decade earlier, the overcrowded city creates cultural homogeneity rather than foster individuality.

In Cole’s pre-club owning life, he agitated against a cashless society (47). Cole argues that corruption will run rampant when institutions will be able to control and gather personal financial data on the individual. In addition, Cole (and Shirley) suggest that technological advances–for example working through “technerlink” terminals rather than in a physical office—will lead to decentralization and destruction of the community (140). It’s not clearly defined how this might occur and why particular individuals wouldn’t still choose work and live close to each other. Perhaps Shirley is speculating on the power of undefined fear? Or, the novel’s message is unformed and scattershot.

Despite Cole and Catz’s action-packed and violent adventures with the amoral City, the plot starts as a maelstrom that soon loses most of its coherence. I could level a similar critique at William Gibson’s seminal Neuromancer (1984). In both novels I found the ambiance and way of telling more captivating than the plot.

Recommended for fans of early cyberpunk, future cities, and SF that screams locale and feel and tone. In these areas City Come A-Walkin’ excels. I look forward to reading more of John Shirley’s work.

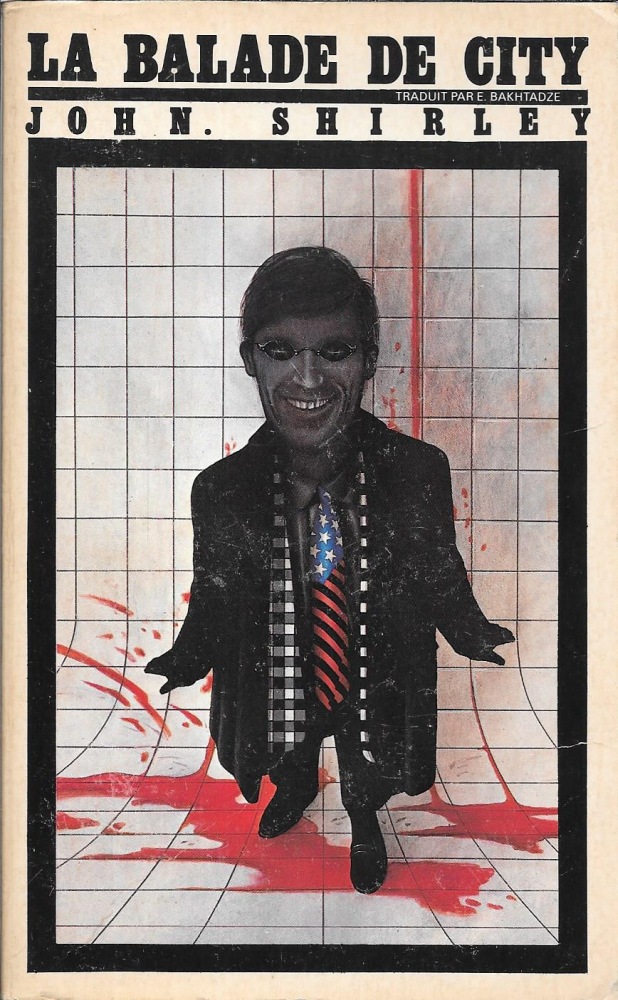

(Keleck’s cover for the 1982 French edition)

(Karel Thole’s cover for the 1981 Italian edition)

(Martin Grundmann’s cover for the 2000 German edition)

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

I love the idea of a city manifest as human fighting back against “the political forces bent on undermining the dynamic interlaced organism of relationships and communities”, and what’s more drawing it’s power from the mass alienation of urban dwellers! That sounds a bit nuts on first reading, but it resonates–for me–with the situationist notion that modern alienation is the negative image of a potential liberatory struggle against alienation. Late 70s/early 80s punk was definitely influenced by situationist ideas, in part, though this is sometimes overstated. A good work on the relationship between punk, the situs and early avant-garde refusniks like the Dadas can be found in Greil Marcus’ “Lipstick Traces”.

The entire book is a bit nuts — in a good way! Other reviewers have described The City as an “amoral superhero.” Which I found a bit shallow. Rather, The City is both a force for good and evil. He wants his people to live in acceptance of each other but simultaneously can be prone to extreme acts of amoral violence. You’d have a lot of fun writing about the book. Just don’t let the bland plot points get in your way. The ideas and overall vibe is far more interesting!

I must confess, I don’t understand what you mean by “situationist notion that modern alienation is the negative image of a potential liberatory struggle against alienation.”

Another reviewer pointed out that City Come A-Walking’ (1980) is one of the few cyberpunk novels that actually centers on and revels in the “punk.” And I agree!

I’m afraid back then I never got past thinking the cover was dreadful. Sounds like I should have made the effort though. As it is, I think Eclipse remains the only novel of his I’ve read.

It’s a riot of a book. As hopefully my review made clear. One reason I try to never get wrapped up in covers!

What did you think of Eclipse? I have that one on the shelf — along with two more of his earlier works arriving soon by mail: Transmaniacon (1979) and Three-Ring Psychus (1980)

Sounds to me like John Shirley read THE USES OF DISORDER by Richard Sennett and made it fictional. As to cashlessness and decentralized work, he was creepily accurate. Witness the coin shortage…its inevitable calls for abolishing cash to “save money” for the gummint (and not incidentally make private banks responsible for issuing currency cards, setting us up for 1837 all over again).

If I didn’t know over 30 ppl in my very own building who died gasping, I’d be a raving conspiracy theorist about COVID-19 and the evils of this pretend plague! Being old–1, paranoia–0

Shirley definitely seems to be running with the idea that and “excessively ordered community freezes adults” that Sennett espouses. The overcrowded but “good” disorder of a city vs. the “dehumanizing” order of the suburb and rural life (which isn’t exactly explored in much detail). I’d have to skim through the Sennett to see what else he’s pulling on. You might be right!

Shirley suspects that organized crime could get its hands on the means of controlling the cashless society. Mostly out of his future metric is a speculation on the role of banks. It’s a nebulously defined fear. And Cole seems like the aging radical who finally gets a new jolt to his system — and the manifestation of the City gives him the justification he needs.

I’m sorry about the Covid impact.

Thanks about the impact. Most of them won’t be remembered because most had no families. Makes it clear how we “value” ppl.

I think private banks (I include the Federal Reserve, a private bank, in this) are indistinguishable from organized crime syndicates: Pay the vig or suffer.

Well, I’m just a little ray of darkness! Time for my nap, I think.

In some ways Shirley’s vision does not connect with those of other early Cyberpunk authors. Here technological inter-connectivity is presented as destroying the individual. Gibson and others seem more ambivalent on the role of technology….

I feel like I need to read John M. Ford’s Web of Angels (1980) ASAP.

I’d heard Ford’s WEB OF ANGELS described as a precursor to cyberpunk too. So, seeing a second-hand copy in a bookstore some time in the late 1990s/early 2000s, I read the first chapter.

The novel turned out to begin in a spaceport on another planet, IIRC, and seemed to be an interstellar adventure story where the different worlds — yes — had a computer network somewhat resembling our internet connecting them together. But then that was true of James Schmitz’s Federation of the Hub stories from the 1960s, too.

Anyway, it sure didn’t feel like proto-cyberpunk to me. It felt like somewhat overwritten space opera based on that first chapter and I put it back on the shelf. I’ve always suspected that Ford gets so much respect from the SF community because he was much-loved and active in fannish circles. They even gush about his STAR TREK tie-in novels. I dunno. It may just be that I haven’t read the right Ford fiction.

As regards the stuff that truly was proto-cyberpunk before Gibson and Sterling, there’s (doh!) Brunner’s SHOCKWAVE RIDER from 1975 (and actually any of Brunner’s Treaty of Rome novels to some extent), Vernor Vinge’s TRUE NAMES, a novella from 1981 —

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/True_Names

— and some Tiptree shorts from the early 1970s, “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” and “Mother in the Sky With Diamonds,” which we talked about the other day. Also, Delany’s NOVA from 1968(!) deserves some props.

Now you remind me, back at the start of the 1980s, I’d pretty much stopped reading science fiction I was so sick of the same old shit. Then around 1983-84 cyberpunk started happening and it was alive and exciting, like this was the stuff we’d all been waiting for. I certainly had.

Ah, well. Nowadays, cyberpunk has itself become the same old shit, of course.

Where are the snows of yesteryear?

Have you read Shirley’s novel though? I can’t tell from your comment.

I’ve read The Shockwave Rider (1975) way back in my Brunner phase pre-website along with Stand on Zanzibar (1968) (my favorite SF novel), The Sheep Look Up (1972), Jagged Orbit (1969), and a whole pile of others.

I’ve read Nova twice but I’ve never gotten around to reviewing it. One of my favorites of Delany’s ouvre.

As for Ford, I get the impression that the dominate perception of cyberpunk is a Gibson-esque concept retrofitted after the fact on early works that “fit.” Ford’s definitely has the technological hallmarks but not the grime and feel. Shirley’s novel has the grime and feel but I would suggest not all the technological hallmarks (there isn’t an internet although the City is a formulation from the network of the city’s minds). In Shirley’s novel future technological changes that will eventually link Americans creates great fear. But they haven’t yet been implemented….

[1] J. B. wrote: ‘Ford’s definitely has the technological hallmarks but not the grime and feel. Shirley’s novel has the grime and feel but I would suggest not all the technological hallmarks.’

I think the key here is the old Gibson line (from NEUROMANCER?) that, “The Street finds its own uses for things.” Things being principally sfnal technologies that previous decades’ science fiction would have shown as exclusively the domain of astronauts, scientists, government agents — straights, in a word — the cyberpunks depicted as used by the street dealers, hackers, crooks, working people, etcetera, of their futures.

Thus, it’s the grime and feel — the depiction of these technologies being used by the working people, crooks, and underclass of the future streets — that seems to me the primary novel and essential innovation that defines cyberpunk.

Thus: Ford, not proto-cyberpunk; Shirley, proto-cyberpunk.

Interestingly, Gibson has mentioned that he went to see Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER when it came out in 1982, and then got up and left the cinema about twenty minutes into it because he found it too similar to the kind of stories he was already writing and didn’t want Ridley Scott’s vision influencing him.

So, again, it’s the grime and feel — forex, the ancient Asian bioengineer in his stall in the street-level market — which BLADE RUNNER has and that makes it also proto-cyberpunk. (Honestly, it’s all the way there, just as much as NEUROMANCER.

[2] You’ve rumbled me, guv. I have not actually read CITY COME-A-WALKIN’ (after the above verbosity). But I’ve read other Shirley and he was of course an actual co-writer with Gibson of one storiy, “The Belonging Kind,” in Gibson’s anthology, BURNING CHROME.

So, yeah, I feel safe in saying Shirley is cyberpunk-adjacent. Here’s an old (1994) interview where he even talks about all that, and the first time he and Gibson met, and how: “I discovered Gibson.”

http://www.altx.com/int2/john.shirley.html