After watching the first episode of the new Fallout (2024) adaptation a few nights ago (I like it!), I impulsively decided to push aside all my unfinished reviews and write about two more nuclear gloom tales. I selected two by Robert Bloch (1917-1994), best known as the author of Psycho (1959), whose SF output I’ve only recently started to explore. Both stories are slick satires that use the nuclear scenario to poke holes in the stories we weave about American exceptionalism and progress.

Let’s get to the nightmares!

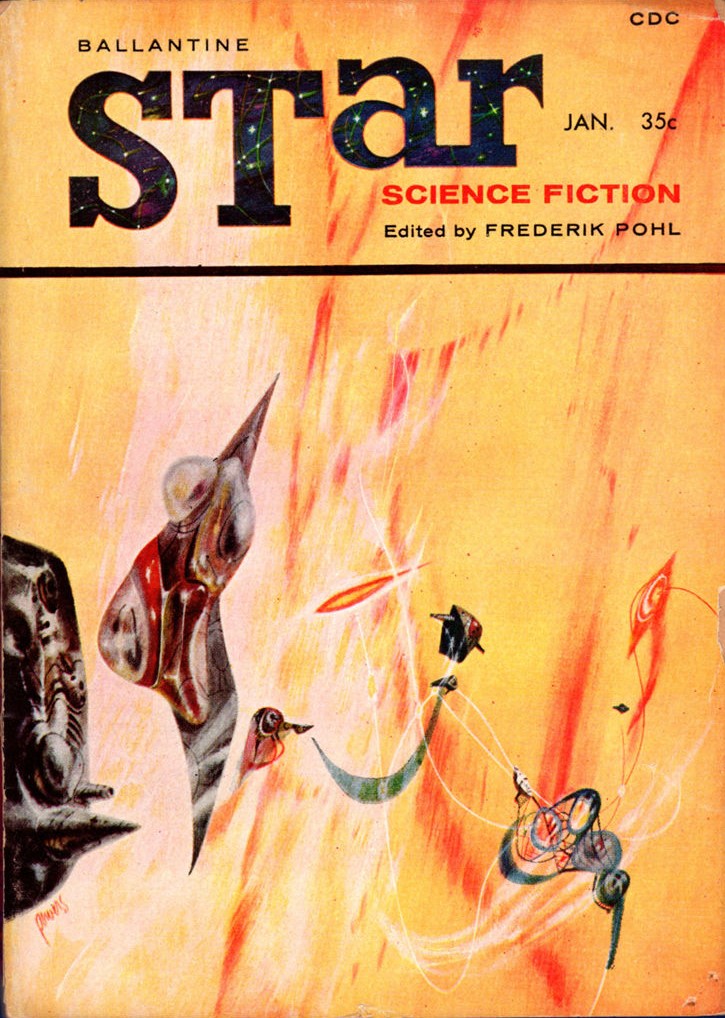

Richard Powers’ cover for Star, ed. Frederik Pohl (1958)

3.25/5 (Above Average)

“Daybroke” first appeared in the only issue of Star, ed. Frederik Pohl (1958). You can read it online here.

Robert Bloch’s “Daybroke” attempts to convey an encyclopedic glimpse of post-apocalyptic destruction in order to satirize an America that allowed the usage of a nuclear weapon. Despite its appealing structure, the story lacks the prose necessary to sear and burn–the last sentence, well, that you’ll remember.

Continue reading