Mark Salwowski’s cover for the 1989 edition

3.25/5 (Above Average)

In The Drift (1985), a fix-up novel comprised of two Nebula-nominated short works–“Mummer Kiss” (1981) and “Marrow Death” (1984), maps a new way forward in an ecologically and genetically ravaged post-apocalyptic age. The entire concoction decays with a sense of grim unease and cavorts around piles of dead that would make a triumvir from the Late Roman Republic proud. It’s a violent, erotic, and disquieting experience that can’t entirely hide its flaws behind the decadent panache.

The majority of the novel transpires within an alternate history version of Philadelphia and its surrounding environs. The jonbar point? If the Three Mile Island partial meltdown (1979) hadn’t been contained. In the power vacuum created by the disaster, the Mummers take over and run a mafia-style government based on extortion and public mutant hunts (two-headed children, etc.). The early sections also revolve around Keith Piotrowicz, who shifts in and out of the main narrative. Keith begins as an aimless young man of firm conscience who seeks to vocalize the questions he’s forbidden to ask: “Why should I spend my life clawing to the top of a garbage heap? Why should I want to kill children?” (4). On a waste dumping trip outside of Philadelphia in the titular Drift, a radioactive zone around Three Mile Island, he uncovers secrets from the wounded body of a visiting reporter named Fletch who collides with his truck. Keith, despite his earlier idealism, uses the fear-inducing secret to rise in the ranks of the city’s elite: “he was a Mummer now” (58).

Later in his life, Keith encounters the young mutant Samantha, a teenage (described as just over thirteen) vampire deported by the draconian National Institute for Genetic Health to a detention facility. Sam appears to have a supernatural ability to see radiation and ascertain the life expectancy of individuals she meets. Robert Esterhaszy, a little person, attempts to protect Sam as she takes on the role of a faith healer. Keith has special interest in Sam due to the connection to her father, who runs a profitable coal mine at the border of a northern polity called The Green State Alliance. As the uneasy alliance sets off to rendezvous with her father while accumulating an assortment of dwellers from The Drift, Keith’s true, horrifying intentions, soon emerge. His presence in the narrative is slowly replaced by Esterhaszy, who forms the real moral center of the story. As the supernatural elements gather and the bodies pile up, a new future seems possible.

A Fragment of the Past, Perpetual, Transformed

The most ingenious element of the novel centers on the “Mummer Kiss” section within the Philadelphia specific landscape Swanwick conjures–in particular the Mummers who run the city. As I have emphasized in my numerous reviews of post-apocalyptic fiction, one endlessly alluring narrative strategy is to take an element of the presence and transform it beyond recognition to demonstrate the cataclysmic nature of a disaster.

For the unaware, the Mummer Parade is an event held in Philadelphia on New Year’s day in which participants dress out in fantastically outrageous costumes (Fancies) and string bands provide elaborate performances. According to Wikipedia, the tradition is derived from the Mummers Play tradition from Great Britain and Ireland. Despite frequently visiting Philadelphia as a child around the holidays, I’ve never attended a parade (maybe it’s a good thing considering the number of controversies over the years!). After reading Swanwick’s novel, I have the unusual desire to at least visit the Mummers Museum.

In this future, the “city government had collapsed after the burnings and public murders” of the refugees from the Three Mile Island meltdown (27). The federal government, overburdened with its own refugee crisis, and other fraternal organizations and charities withered away. The Mummer clubs, previously created for “the sole purpose of putting together a troupe to march on New Year’s Day” remain and begin to absorb the functions of government (27). The rituals of the original parade are transformed into weapons of terror and social control. The club captains, still elected by their members, become new-fangled “feudal lords” (28). This ranks among the most bizarre future governments I’ve encountered in SF.

In the Drift contains some memorable scenes, unique setting, and powerful moments. Despite its short length, the fix-up nature creates a variety of cohesive and connective portions that don’t entirely gel together. Swanwick’s tendency to eroticize questionable sexual encounters and use of the n-word (and not only by characters we are supposed to think are racist) will alienate many readers–for good reason. Simultaneously, the novel contributes in a radically progressive way to disability in SF–the only truly heroic and morally upright character is Robert Esterhaszy, the father Sam (and her daughter) never had. I found Swanwick’s desire to provide science fictional explanations for trope mythical figures (vampires) in the third section entirely unnecessary (I am reminded of Richard Matheson’s far more satisfying 1954 novel I Am Legend).

Recommended only for diehard fans of post-apocalyptic fiction.

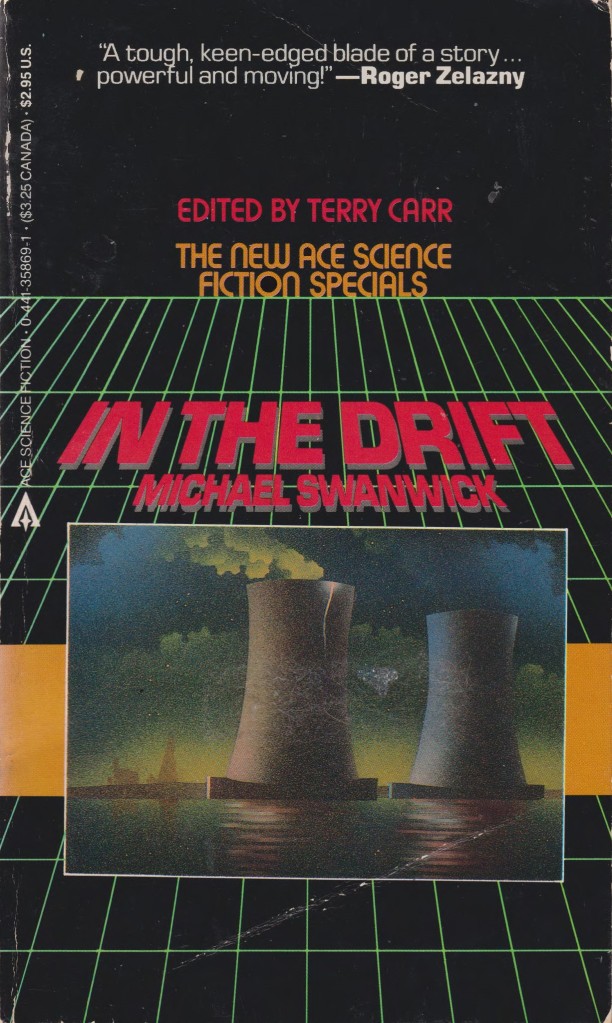

Rob Lieberman’s cover for the 1st edition

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

It’s very much an apprentice first novel, although Swanwick was already publishing short fiction of serious note. His early short story, ‘Ginnungagap,’ in 1980 —

https://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?41372

–brought all the same kind of innovative ideation to space SF that Bruce Sterling’s ‘Mech-Shaper’ would, but predated Sterling’s first story of that kind (‘Swarm’ in 1982) by two years.

By the time Swanwick hit his stride as a novelist, unfortunately, he’s beyond your 1984 cutoff point for consideration

I agree on both points — this felt like an apprentice first novel and that he was better at the short form in the early 80s. The previously published sections of In the Drift both garnered a Nebula-nomination (as did “Ginungagap”) and were far more cohesive and interesting than the conjoining and connecting elements.

Interesting review. I know Swanwick’s name but have never read any of his stuff, seems like his short fiction may be the place to start?

Thank you.

Yeah, like the two previously published sections of this novel (“Mummers Kiss” and “Marrow Death”), Swanwick collected a large number of Nebula Award nominations for his early short fiction in the early 80s. Those short fiction portions were the best parts of this novel. I also assume Mark will agree that he’s best known for his Nebula-winning and Hugo-nominated novel Stations of the Tide (1991).

Due to my perpetual interest in the dystopian and post-apocalyptic, I am most interested in reading the following two early short fictions of his next: “The Feast of Saint Janis” (1980) and “Walden Three” (1981).

A good starting place is his early collection GRAVITY’S ANGELS, Arkham 1991, but there’s a paperback. It’s a fairly fat book containing a number of short pieces (including “A Midwinter’s Tale,” which I found particularly elegant) as well as several of the novellas mentioned in this thread.

What is “Midwinter’s Tale” about? I see it was also in an anthology titled Tomorrow Bites…. so vampires or werewolves or something in the future? Seems to a running interest in these supernatural mythological figures as the former crops up in In the Drift.

It’s about a woman on a distant planet being stalked by a predator who wishes to eat her brain, with more than gustatory consequences.

Ah! Sounds way more interesting.

Looking at his ISFDB page, he was in Asimov’s a lot in the 1980s. “Snow Job” and “Anyone Here From Utah?” I recognize just from the title. Looks like I read “Marrow Death” in Asimov’s too. The cover of “In the Drift” sets off massive nostalgia for the Ace Special art stylings. Those were the days.

If you’re tempted to return to any of his early stories, please let me know how they are! As I mentioned to Shaky Mo Collier above, I’ve already picked my next two Swanwick fictions (at least as of now): “Due to my perpetual interest in the dystopian and post-apocalyptic, I am most interested in reading the following two early short fictions of his next: “The Feast of Saint Janis” (1980) and “Walden Three” (1981).”

I didn’t get the impression that Swanwick was providing “science fictional explanations for mythical trope figures” when he tells us about the vampires (AKA people with Short Bowel Syndrome); the big enemy/adversary in the Drift stories is an appalling ignorance and lack of education everywhere. Sadly, so is knowledge and information; the Mummers mafia-style government is based on keeping the vast majority ignorant of just about everything, because if everyone knew what was really going on, society would self-destruct. And so people believe that vampires (SBS mutants) are undead rather than genetically damaged; witches, witch doctors and conjure men (mutants with actual psychic talents and people able to pass themselves off as such) are considered real witches, etc. Swanwick depicts a frighteningly believable post-apocalypse setting where the choice is between the “quiet terrorism” of the Mummers’ Clubs and what the revelation of the truth would do to the world; there are no good solutions to this dilemma. The only choices are really bad as opposed to slightly worse.

Maybe a more apt way I could have stated it would be to say “Swanwick creates a science fictional manifestation of the mythical trope figure” of the Vampire. If I am not mistaken, they say they have Short Bowel Syndrome to avoid acknowledging to others (and to delude themselves) the existence of the mutation as that would suggest Philadelphia and other areas are within the titular drift. They aren’t actually suffering from Short Bowel Syndrome (blood consumption certainly isn’t needed to survive with the real illness). Swanwick definitely creates a “vampirism” caused by the nuclear disaster. I don’t remember the “people believe that vampires (SBS mutants) are undead” part. Other than that, I don’t substantively disagree with your description of the novel.

It seemed to me that the SBS illness wasn’t claimed by Drifters to explain their mutations as something that they acquired outside of the Drift–a lot of people are going in and out of the Drift at the time “Boneseeker” occurs, and the fact that many of them are mutants is becoming commonly known at this point. The big secret is still what’s happened to Philadelphia, but fear of gene damage has been overridden by the desire for profit held by the rulers of the nations around the Drift (Greenstate, Lakes Federation, New York Holding, etc). They want to make money out of the Drift, which requires them to deal with the Drifters.

You’re right, Swanwick doesn’t refer to the vampires as “undead”–that was just my own usage. With the kind of stuff people like Celeste say (telling stories about cannibals and mutants returned from the dead) and the way they gang up on Samantha when she tries to buy some blood, these folks seem driven by ignorance and superstition (not to mention the fact quite a few of them are mutants). Talking about hirsute people as werewolves–that’s pretty weird, and especially when you can see any number of visible mutants all around you. I don’t know know the SBS illness would actually work, but it seems to be applied to both the Laings and others like Celeste who apparently don’t have genetic damage.

Reread the portion when the various genetic mutants caught by the authorities interact with each other on the deportation train. They are all mutants. However, when they discover that Sam is a vampire and tries to get a child to get her animal blood, her fellow mutants join in on the attempted stoning. In that exchange, they initially talked about SBS. I am convinced that SBS is a fiction (obviously also a real disease that people have now) invented by the mutants to explain away their condition vs. address the reality and stigma of the actual issue. Perhaps we are both right — it’s a mutant version of SBS that causes them to need blood. But even then, the name of a real disease covers up the reality of their SFictional one. I am currently far away from my SF collection else I’d recheck those exchanges that are lodged in my memory.

I’m a Philly native. I read this when it came out, and remember it because of the Mummers angle.

I thought that was the most interesting element of the story — by far.