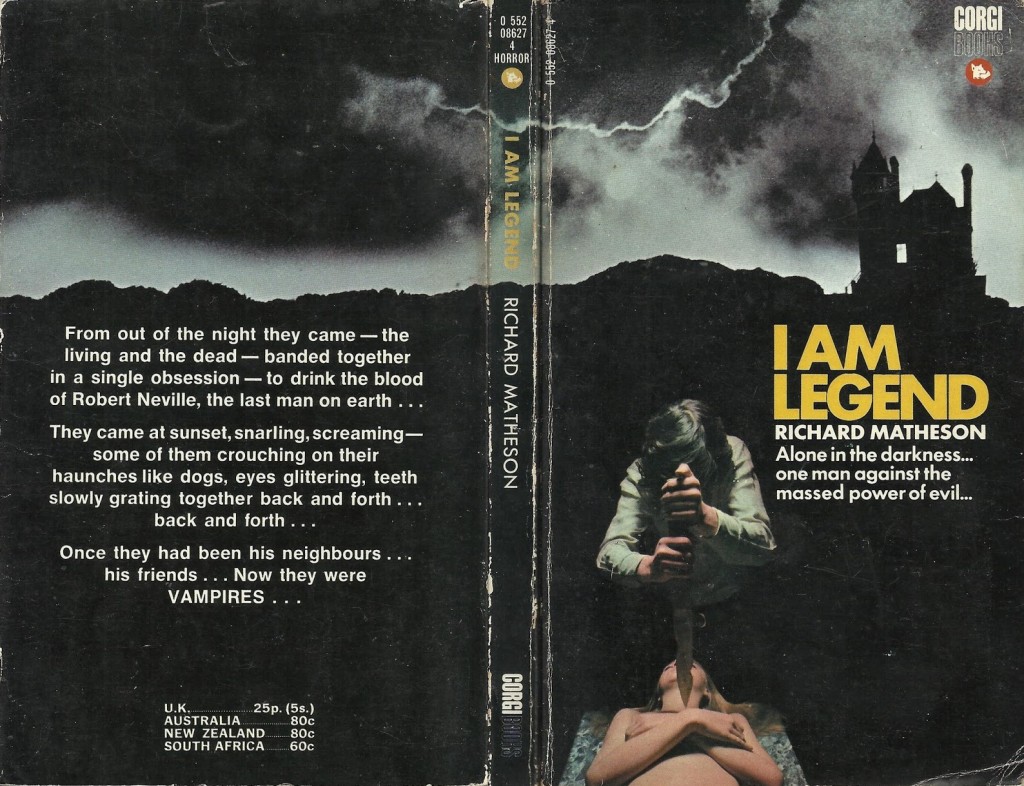

John Richards’ cover for the 1956 edition

4/5 (Good)

Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954) is an influential SF vampire/zombie novel that spawned three film adaptations (I’ve watched the first two) and inspired directors such as George A. Romero and Danny Boyle, game designers such as Tim Cain (Fallout), and countless authors. The subject of the novel–man attempts to survive an onslaught of vampires, caused by bacterial infection, that act like smart(er) zombies in a post-apocalyptic wasteland–normally isn’t my cup of tea. I’m the first to admit that I picked up the novel entirely due to its historical importance. And I’m somewhat glad I did! While the physical onslaught of vampiric zombies didn’t interest me, the main thrust of the narrative concerns the mechanisms of grief and sexual frustration in the burning wreckage of one-time domestic bliss.

The Rituals of Solace and the Path out of the Haze (*spoilers*)

Richard Neville, a tattooed war veteran mysteriously immune to the vampiric affliction sweeping America, spends his days lathing stakes, traveling short distances from his home killing vampires, hanging garlic, listening to Beethoven, and drinking. The female vampires attempt to cajole him from his house with lewd acts: “there was no union among them. Their need was their only motivation” (12). The facts about the vampires seem straight from gothic legends of the past: “their staying inside by day, their avoidance of garlic, their death by stake, their reputed fear of crosses, their supposed dread of mirrors” (16). Intermixed with Neville’s daily ritual are intense moments of disillusion and sadness as he remembers the domestic happiness before the disease within the same walls he still occupies. He deeply loved his wife Virginia and his young baby Kathy. When he dreams about Virginia his “fingers gripped the sheet like frenzied talons” (11). He remembers their final conversations. Her death. His grief. And her return… And when the despair builds he slips back into the routine again: “reading-drinking-soundproof-the-house” (21).

Two ideas jolt him from his alcoholic malaise: 1) the faint possibility that “others like him existed somewhere” (18). 2) a growing desire to uncover the scientific rationale behind the vampires, and perhaps, an ability to more effectively kill them. Neville, little educated in science, throws himself into his studies (i.e. an excuse for Matheson to divulge extensive mind-numbing passages of rudimentary bacterial theories that never make the “reality” of vampires any less scientifically inane). He uncovers the reason behind how the disease is spread, why vampires need human blood, and how they are able to animate a dead body.

The narrative gains intense emotional heft, if it didn’t have it already, when Neville comes across the emaciated shape of a dog in the middle of the day (vampiric dogs bark at night): “Why pretend? He thought. I’m more excited than I’ve been in a year” (82). He spends days and days domesticating the beast–which has developed its own ways to survive the predations of the vampires at night. And at its death, he is again crazed by grief. And then a woman appears on one of his voyages…

The Male Sex Drive in the Wasteland

I enjoyed I Am Legend as an allegory of nuclear terror. Matheson makes clear that the vampiric disease–spread by bacteria in dust clouds (i.e. paralleling fallout)—is a metaphorical (and mythological) manifestation of humanity’s fears of the end present in the 1950s. Virginia asks Richard whether the bombings caused the disease and Richard answers, “and they say we won the war” (43). Matheson implies a limited nuclear conflict in the near future that reflects growing knowledge of fallout after Americans learned about the “Ivy Mike” Hydrogen bomb tests in 1953 [1]. The vampiric disease represents America’s existential dread present in a rapidly changing post-WWII world and how the suburban American way of life is under threat. Neville’s discoveries of the nature of vampirism after the apocalypse suggests we too might understand the true impact of nuclear weapons on the wrong bank of the Rubicon.

Lima de Freitas’ cover for the 1958 Portuguese edition (below), and to a lesser degree John Richards’ cover with its staked nude female for the 1956 edition (above), reflect an omnipresent thread of sexual chaos amidst the incomprehensible horror of vampiric holocaust that runs through the novel [2]. Lima de Freitas’ figure of Richard Neville does not have his eyes on the burnt buildings of the surrounding city but on the suggestively splayed nude female body of a vampire. At night that body with rouse itself and mill around Neville’s house attempting to cajole him out with macabre parroting of female sexuality: “The women, lustful, bloodthirsty, naked women flaunting their hot bodies at him. No, not hot” (21). Neville, alone, is possessed by perverse sexual desires. In one instance he ponders why he always experiments on female vampire bodies he collects while they sleep during the day: “Why do you always experiment on women? […] What about the man in the living room, though For God’s sake! He flared back. I’m not going to rape the woman!” (48). But he can’t help but notice her “torn black dress” with “too much [..] visible as she breathed” (48). In another instance, consumed by the heat of his loins Neville finds himself removing the bars of his door in an effort to run out into the night–“Coming, girls, I’m coming. Wet your lips now” (21).

Elaine Tyler May analyzes the juxtaposition of sex symbols with nuclear devastation in American popular culture–think bikini bathing suit, an attractive woman as “bombshell” or “Bill Haley and His Comets singing about sexual fantasies of a young man dreaming of being the sole male survivor of an H-bomb explosion” [2]. The home provided a form of “sexual containment” [3] that would be released in terrifying forms in the case of apocalypse. If the home falls, society falls. And Richard Neville attempts to preserve his home in I Am Legend and avoid the endless temptation of flesh in the burnt wreckage of suburbia that surrounds him. And when he gives in to his sexual desires and lets a new woman into his house in a confused attempt to recreate what he had lost, the end has already been spelled out.

Notes

[1] For more on what Americans knew about nuclear testing–and saw on TV–and when they knew it, check out Robert A. Jacobs’ concise and fascinating The Dragon’s Tale: Americans Face the Atomic Age (2010).

[2] As I read I Am Legend as an allegory of nuclear fears, I used Chapter 4 “Explosive Issues, Sex, Women, and the Bomb” of Elaine Tyler May’s Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (1988, revised edition 2017). I am riffing of some of her ideas.

[3] May, 107.

[4] May, 108.

Lima de Freitas’ cover for the 1958 Portuguese edition

Uncredited cover for the 1960 edition

Jack Gaughan’s cover for the 1967 edition

Uncredited cover for the 1971 edition

Uncredited cover for the 1970 German edition

Murray Tinkleman’s cover for the 1979 edition

Stanley Meltzoff’s cover for the 1st edition

Sanford Kossin’s cover for the 1964 edition

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

I didn’t realise this story was as strong as you pointed out. Fantastic read and I will definitely pick up a copy now.

It’s a short novel. I read it in an afternoon. Definitely more transgressive in its sexual content than I was expecting!

I can’t wait to read to it now.

I have read and reviewed better books recently — P. C. Jersild’s After the Flood (1982) and Tevis’ Mockingbird (1980).

The historical context (right after the Hydrogen bomb tests in the US) fascinates though — and you can see it clearly in Matheson’s paranoid last man novel.

I’ve read Matheson’s collection “Steel” and disliked it enough that I was never tempted to try this book.

The first Matheson collection I read — Third from the Sun (1955) — had a collated rating of “Average” but a handful of worthwhile stories: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2015/03/22/book-review-third-from-the-sun-richard-matheson-1955/

Matheson is an interesting case. The Matheson stories I’ve read showed a talent or skill — though either word is too strong, really — for writing a kind SF/fantasy/horror that entirely dispensed with the bother (for normie readers) of any science-fictional conceptualization — that in fact had dumb premises that didn’t make any sense at all and didn’t care about it.

It became a very successful genre in itself via Matheson’s — and his peer Charles Beaumont’s – adaptations of their stories for 1960s television series like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits.

It’s the genre that Stephen King, who counts Matheson as a primary influence (though King is a far better writer) operates in today, and that Harlan Ellison (who actually sold some scripts to those shows) was also an upscale example of. Literally, there are King and Ellison short stories that are clearly re-writes of specific episodes of those shows.

So:significant from the POV of the history of the SF genre and culture as a whole. Not my thing, though.

I’ve never seen an episode of 1960s television series like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits! Haha.

I mean, he tries to generate “science-fictional conceptualization” and those are definitely the passages that are far less impactful than the emotional toll Neville experiences. At its heart this novel tries to provide a scientific explanation of a historical myth.

But I do agree with the novel’s importance in the history of SF genre and culture. And how it’s not entirely my thing either…

“The vampiric disease represents America’s existential dread present in a rapidly changing post-WWII world and how the suburban American way of life is under threat.”

I prefer to think of the suburb itself as the true wasteland, made possible by the vampire of capital (to use one of Marx’s telling phrases): the American Dream as vapid, denatured, empty, etc. This, I feel, is the real fear of so much 1950s and 60s culture, that capitalism “at its best” is the end not the pinnacle of material want and success. Philip K Dick nails this sense of the doom of suburbia in works like “The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch”.

But it’s already there in “I Am Legend”–a novel I love by the way (how can you give it a measly “good”?!). In particular, it’s end–which has been botched by all of the film adaptations–underlines the dead end of the American Dream, and Neville’s hopeless wish to hold on to it.

Neville only remembers the suburban life fondly within the matrix of the story. Of course, he focuses his memories on the love of his wife and child. Hence the phrasing I used. But I take the point that Matheson’s critique might be directed at the suburb itself as in other stories of his I’ve read from around the same time — for example, the spectacular “Mad House” (1953) which I reviewed in his collection Third From the Sun (1955).

But the end… it fails because its not the genuine love he experienced before. It’s a charade and he knows it. And yeah, I guess a macabre charade of the American Dream in the last house standing. But could this not be a warning of what is to come if everything collapses? Neville’s final posturing is a final attempt at normality as it all fades away. I do feel the story does fit within common contemporary views of the dangerous sexual landscape that emerges after the apocalypse. The subversive sexuality isn’t really subversive in the context of fears of what would happen if the institution of the American family collapsed.

As for my rating, I adore the historical context of the novel and I point out its historical importance. But the entire let’s come up with some ridiculous point-by-point scientific explanation for Vampirism and revisionist interpretations of the Black Death and past plagues…. grated on me and muted its allegorical impact. There are counter arguments of course — Matheson is essentially stating that scientific knowledge won’t save us in the end. But everything else rates much higher in my book. And I HATE VAMPIRES AND ZOMBIES! hahahahaha. I enjoyed it far more than I thought I would.

Don’t get me wrong, I like your review and think your argument about “sexual chaos” is right on the money. I suppose I was struck by the idea of the phrasing of a “threat to suburban life”, given the threat that is suburban life.

Speaking of sexual chaos, I read his “The Shrinking Man” last year, and was bowled over by its wonderful take-down of 1950s masculinity. Highly recommended.

No worries. I’m all for debate and counter argument. I revised my comment extensively. I hope I’ve clarified my views.

I found the suburb critique angle more muted here than in “Mad House” (1953) so I read the threat as a more general response to nuclear fears that will impact all — including suburban life. The review probably dodges how Matheson is also critiquing suburban life… at the same time.

I’m pretty sure I’ve seen the “The Shrinking Man” movie at one point. I haven’t read the book. I’ll keep it in mind. Thank you! And I’m all for take-downs of 1950s masculinity.

The film is good but the novel is great. But can you trust me?

I should check out ‘Mad House’. Like yourself and others I’ve had mixed results reading his short fiction.

I’m almost certainly overstating the suburbia is wasteland line. It’s been a while since I read “I Am Legend”. Your review makes me want to reread it.

Meanwhile, the wasteland that is my suburb is all too present and real. Inescapable dare I say? Roll on its destruction…

You know me, I don’t only read to find great pieces of literature. I’m bound to get something out of the novel even if it isn’t my favorite thing ever. Hence why I got so excited about this novel and Moudy’s “The Survivor” even if my ratings didn’t exactly reflect my excitement. The social history surrounding it excites!

For all I know I’m misremembering “Mad House.” Most of my memory of it is tied up in the short review I wrote…

Speaking of 50s takedowns of suburbia, I finished Sturgeon’s “And Now the News…” (1956) moments ago for my media series. He even identifies how suburbia diminishes interaction between people vs. life in a city (although he has his main character take a train to work vs. drive a car which is a bit off).

I have my own built in hatred of the suburb. I moved from rural Virginia to a suburb in Texas in my teens. I remember the almost existential diminishing of horizons. I was initially less horrified as the suburb wasn’t completed and there were tracks of land to explore but those were promptly bulldozed… Which made me hate it even more.

The Sturgeon has made it’s way to the top of my to read pile. Thanks! Tho I should probably read the Moudy while discussion is still relatively fresh.

I read Charles V. de Vet’s “Special Feature” a few days ago on the back of its recommendation by one of your readers. It’s definitely up your alley, if perhaps not as wonderfully speculative about urban alienation as some of the stories we’ve read over the years.

Sadly, I never had your good fortune to spend some of my youth in the country. I’m a city boy born and bred. Tho maybe I am luckier than you for not having known what I’m missing. Maybe…

De Vet turned the story into a novel — his only solo novel (he wrote a few with Katherine MacLean).

I quite enjoyed this novel when I read it, but it didn’t leave any real impression on me, probably because I had already read much better novels and pieces. It’s far from being great though. I don’t think Matheson is such an imaginative or original author. I know you like it for it’s themes though, but even they weren’t strong enough to take my attention.

I think this novel is the definition of an imaginative and original work. There simply weren’t zombie/vampire novels like this one at all. But the premise definitely is original. Maybe you meant to say its delivery was imaginative or original? Even then I don’t completely buy your argument — this is an intense case study of grief, not something terribly common in genre novels at the time.

It’s delivery probably was imaginative or original, and I think you’re right, there weren’t zombie/vampire novels like this one, and the premise is original, but it Isn’t memorable. It was influential on later SF though, such as George Martin’s “Ferve Dream”, which is also about vampires of a natural origin and contains cutting edge themes

Well, I’m never going to forget the dog chapter…. or Neville relentlessly obsessed with the zombie women outside his door…

FEVER DREAM, by the way, is exceptional. I am not a fan, in general, of vampire novels, but that one is really good.

Like I Am Legend, I don’t think it’s for me. But also like I Am Legend, there’s a chance the stars align and I feel the compulsion to give it a read!

“… And Now The News” is truly a great story, one of Sturgeon’s best. Having MacLyle (famously named for two of Heinlein’s pseudonyms as a nod to the help Heinlein gave Sturgeon) take a train to work is entirely characteristic of many suburban workers at that time (and to a lesser extent up until now.) It is not easy or cheap to park in a city downtown, so you take a train. My own home town (Naperville, IL) is the second to last stop on the Burlington Northern out of Chicago, and many people take the train to work. (The neighboring unincorporated village of Eola (now, I think, incorporated into either Naperville or Aurora) was named such as it was once the “End Of the Line”.)

As one who has lived in suburbs his whole life, and who has generally positive memories of his childhood, I find the somewhat cliched standard criticism of suburbs as soulless and arid etc. etc. to be just that — a cliche, a lazy trope. But Sturgeon’s story (which is about much more than that) remains powerful.

As for I AM LEGEND, I haven’t read it, and have little to say, and indeed I barely remember the Heston movie, THE OMEGA MAN, which I saw at a very young age.

I’ll talk more about the story when I review it.

I don’t find it be a lazy trope. There are of course lazy authors who parrot the basic points without much introspection. This historical background is so fascinating. The suburbs represent white flight and the abandonment of the cities (and the people who lived there), American equation of white home ownership vs. minority ownership, increasingly limited options for women (who were often trapped at home more than before especially if the father took the car to work and there wasn’t public transit), suburbs were 99% white and thus interaction with other races decreased (the race line was real!), etc. There’s so much historical background that it’s ripe for SF to explore. I am, of course, not saying there weren’t some benefits and that some didn’t enjoy them.

I live in the first suburb of Indianapolis (built in the late 1880s) — it’s now part of the larger urban center as the city has grown so much since then. The train (I guess more a trolly) was completely removed at the behest of the car lobby in the early 20th century, and it was a direct route downtown (4 miles) that I wish still existed. Of course, there’s a ton more space in Indianapolis than Chicago. Chicago, New York, etc. = rare American cities with a functional and extensive public transit system. No such thing exists in the rest of the once-industrial Midwest. Parking is never a problem. There is no metro system. There are only in the last few years a dedicated bus lane on one North/South route and one under construction East/West. It’s really really really sad that it’s taken this long.

i.e. maybe Sturgeon is thinking public transit in New York/Chicago vs. the average American suburb in the average American city.

To be clear — there is plenty of criticism — or examination — worthy of being done of suburban life; and most acutely the divisions it exacerbated between white people and black people is one serious issue. And the whole car culture thing is interesting too — and how public transportation was actively suppressed, most famously in LA, but in other places too (and I didn’t know that about Indianapolis) is a scandal.

But my problem is not interrogations of such things. It is the sort of default view — that it seems to me is supposed to be taken as axiomatic, not even worthy of proving — that life in the suburbs is (or was) dehumanizing, and everyone there had no inner life etc. etc. I know I’m exaggerating, and I know I’m oversensitive, but that’s how it seems to me often.

I grew up in a house where I could go out my backyard and over the road behind it and walk, it seemed, all the way to Champaign without hitting signs of civilization — and that’s not possible now — it’s all subdivisions! So I did have access to open country, to creeks and field and copses and all. And lots of people didn’t.

I dunno, guys. Is there anything significant left to be said in 2022 about the soullessness of the American suburbs, given that it’s 1950s-era American mainstream lit’s primary — almost one and only — theme.

From Richard Yates’s REVOLUTIONARY ROAD and John Cheever’s stories like ‘The Housebreaker of Shady Hill’ (all the men ride the train in to Manhattan) at the high end, to Sloan Wilson’s THE MAN IN THE GREY FLANNEL SUIT and J.D. Salinger, and early Vonnegut, it’s almost like they didn’t write really write about anything else. It’s even all over Nabokov’s LOLITA, though a lot more is going on with that novel.

Cheever’s stuff is still great; he was a real artist and a weirdo, with his WASP facade covering his barely repressed homosexuality and serious alcoholism. But a lot of other 1950’s American mainstream lit comes over as a bit of a bore these days. Maybe the most interesting thing about it is what it leaves out— which is the stuff Cheever hinted at.

I came over to the US in the early 1970s because my father went to work for an American corporation. So I saw some of the tail-end years of that generation of ostensibly straight white guy executives and middle-class types. And what struck me was that many of them drank like — well, not like fish, but the three (or five) martini lunchtime every day really was a thing. My sense was that many of these men were either deeply effed-up or there was a void inside, and they drank to repress it or cover it up. In quite a few cases, what they specifically never talked about — and never wanted to talk about — was what had happened to them in WWII and the Korean War, because they had what we’d now recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder. Consider, for instance, Gene Wolfe’s hints about his condition after his return from Korea.

I’ve gone some ways away from I AM LEGEND, I admit. Sorry.

In academic study there’s plenty to be said. I recently read the Dianne Harris’ brilliant Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (2012). And her arguments about how the American consciousness when it came to formulations of ownership were new at the time. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/little-white-houses

Note: My parents are architects so all this stuff is extra fascinating to me.

The criticism of post-war suburban life as empty and soulless is certainly a cliché if such a “criticism” is left merely at the level of assertion. But being a cliché isn’t proof of its falsehood. Indeed, it’s often demonstrative of precisely the opposite.

I grew up in suburban Sydney in the 1970s and 80s, and by the time I was in my mid to late teens was chaffing at the bit to escape the real boredom that I experienced in this setting. Did I imagine this? Not at all. Indeed, I recall not only its representation in broader culture (this was the time of punk rock after all), but also how this experience was shared not only by many of my teenage friends, but also older and younger siblings and relatives. My experience was of a widespread malaise and frustration with suburban life, particular among youth. Which is not to say I had never enjoyed this life, nor that I had been able to find corners of it that appeared to resist this (to name only two: my nerdish discovery of role-playing games and second-hand bookstores). But such experiences, at least retrospectively, appeared to cut against the grain of suburban experience rather than exemplify it.

I think Joachim’s caveats about the structural problem of the suburb is probably the best way to try and flesh out this claim. Then we can examine suburban development empirically with an eye to its conscious and unconscious results: i.e., how the expansion of suburbs was carried out deliberately, in the sense of various states and instrumentalities trying to sculpt a particular class and racial order, and haphazardly, in the sense of the unforeseen problems that surfaced as a result of just such an ordering (unforeseen, that is, by the self-same states and instrumentalities).

Mark, you are quite right, it was a very ’50s thing — and your suggestion that it was influenced to a perhaps considerable extent by what happened in the war (especially WWII) is intriguing and probably right.

I don’t know the alcoholism stats or any of that but it sure does seem like there was a LOT more drinking in those days. (In a way, did more driving eventually reduce drinking? — much easier to pour yourself into a train car and sleep it off on the way home than to drive home drunk.)

My Dad was in Korea, got there late and spent about three months in combat, in an artillery unit. He didn’t talk much about it — he did say he was offered a chance to go to Officers’ training but he didn’t take them up on it partly because as far as he could tell the casualty rate among newly minted artillery Lieutenants was astronomical (as they were often assigned forward spotter duty.) Of course, as it turned out the War would have been over by the time the training was done, and he’d have been a peacetime Lieutenant for however long they required (I dunno? Three years?) instead of being mustered out right away. And I probably wouldn’t be here!

He was never a drinker to any extent — I saw him drunk once in my life. He would have one martini when he got home from work and that was it, maybe a (crappy — he liked bargains) beer or two on the weekend after mowing the lawn. And I never really tried to draw him out about the war — I wish I had now, but it’s too late. But he was (or seemed to me) a happy man, and stayed active in various things (civic, such as zoning boards or volunteering for the census, plus lots of travel) all his life.

I learned right before my grandfather died that he served in Korea — briefly. He finished training, was sent to Korea, and then the war ended moments later. I never figured out if he went to college because of the GI bill. Maybe his lack of actual service meant he never wanted to talk about it (maybe his friends saw actual combat).

But my grandparents were the definition of a suburban 50s family. Lived outside of Philadelphia, grandmother went to college and shifted majors to home economics (I think at the instigation of her parents but I’m uncertain), got married in college (I think)… she never held a job. Had meals on a week rotation (the 50s classics including salad with cottage cheese and jello), and was profoundly unhappy (I won’t get into it too much). She wrote poetry relentlessly–my dad still has all of her volumes–with her omnipresent box wine and cigarettes.

Born of Man and Women is one of the most brilliant debuts in the genre.

II: Vampires? Carmilla! Am in Love!

I reviewed “Born of Man and Woman” a few years back. I thought it was solid and effectively creepy. https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2015/03/22/book-review-third-from-the-sun-richard-matheson-1955/

To clarifiy about the novels of Katherine MacLean and Charles de Vet — they only actually collaborated on one novel, which I think is best called SECOND GAME. That novel appeared in three versions, each longer than the one before. These were the novelette “Second Game” (Astounding, March 1958), the short novel COSMIC CHECKMATE (Ace, 1962), and the somewhat longer novel SECOND GAME (DAW, 1981).

I don’t know who did what on those three versions, which are all the same basic story, but if I had to guess, MacLean and de Vet collaborated fully on the novelette; and they MAY have collaborated on the expansion to COSMIC CHECKMATE, but mostly likely (and this is purely my speculation) the expansion to the DAW 1981 version, SECOND GAME, was mostly or entirely by de Vet.

The sequel, THIRD GAME (DAW, 1991) was entirely by De Vet.

De Vet, as you note, published one other novel, SPECIAL FEATURE (Avon, 1975).

Thank you for the clarification. I need to read more of MacLean’s short fiction. I adored her novel Missing Man (1975) (an expansion of her Nebula-winning short fiction by the same name): https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2011/10/08/book-review-missing-man-katherine-maclean-1976/