Photo of Chukwunonso Ezeiyoke’s Nigerian Speculative Fiction: The Evolution (2025)

Over the last few years, I have highlighted a smattering of the vast range of spectacular scholarship on science fiction in my reviews and Exploration Log series that intrigue me.1 Today I have an interview with Chukwunonso Ezeiyoke about his brand new book Nigerian Speculative Fiction: The Evolution (2025), the first ever monograph on Nigerian speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) (SF). Due to the focus of my site and research interests, I focused my questions primarily on the historical portions of his book.

You can buy a copy directly from Routledge here or on Amazon. As academic works aren’t the cheapest, can also request your library procure a copy.

Let’s get to the interview and the fascinating world of Nigerian SF!

Graphic created by my father

1. Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview. Can you introduce yourself and your interest in speculative fiction?

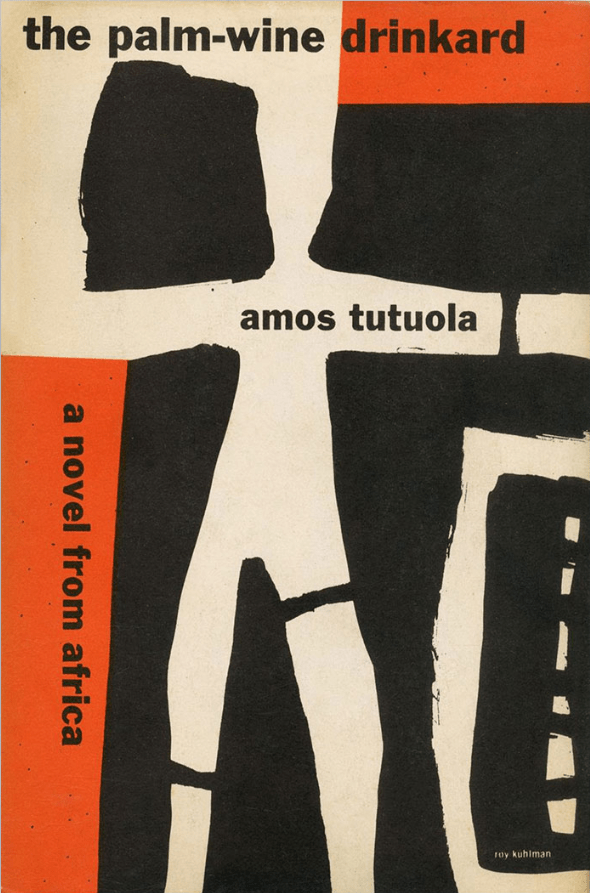

Thanks for inviting me to this interview. My name is Chukwunonso Ezeiyoke. My PhD is from Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. My interest in Speculative Fiction is a long one. The book that did it for me was Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952). I posted about my journey on Facebook a few days before my book, Nigerian Speculative Fiction: The Evolution (2025), was published. The story is this: when I was 15, I saw The Palm-Wine Drinkard on my brother’s shelf. The book’s magic engrossed me. My brother saw me reading the text and pointed out that Things Fall Apart (1958) by Chinua Achebe is proper literature I should engage with, not Tutuola. I read both books during the holiday, and I couldn’t shake myself from the magic of Tutuola’s world.

Since then, I have continued to ask myself why Tutuola’s text is not considered an essential work of art. Fortunately or unfortunately, the question has shaped my entire academic trajectory since then. Even during my undergraduate dissertation, it was the younger me trying to argue in favour of the kind of writing Tutuola does using the philosophy of John Dewey. Still, after my undergraduate studies, the question haunts me. Twenty-three years later, I figured out an answer that I considered adequate to the question. The answer is the book, Nigerian Speculative Fiction: The Evolution (2025).

Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the 1953 US 1st edition

2. First, a point of clarification: you use the term “speculative fiction” as your operative generic category. What is your definition? What does it encompass?

I agree that, to a certain degree, fantasy, horror, and science fiction have their unique aesthetics that differ from one another. For instance, I follow Carl Freedman’s definition in the monograph regarding the distinction between science fiction and its adjacent genres.

However, I read all of them together in the book as speculative fiction for two reasons. One is that the definition of science fiction adheres to Western modality. Thus, many scientific phenomena that do not align with this Western modality are dismissed as not scientific enough. One instance that quickly comes to mind is African traditional medicine. Indigenous African doctors have used herbs to successfully cure illness. However, their methodology does not align with Western medical procedures. So, their procedure is often treated as pseudoscience. Two short stories that address the theme of the disregard accorded to African indigenous medical knowledge due to its different methodology from Western medicine that come to mind are “The Leafy Man” (2014) by Dilman Dila and “Fruit of the Calabash” (2020) by Rafeeat Aliyu. If I use science fiction as it is currently defined, this herbal scientific medicine, whose practitioners often merged their practice with indigenous religious rituals, as seen in “Fruit of the Calabash”, would be excluded because it does not meet the benchmark of Western validity in scientific methodology.

Because of this, I decided to use speculative fiction. Speculative fiction for me deals with ontology (realities beyond the current human episteme), which differs from epistemological knowledge (knowledge within the current human episteme). For my analysis, ontological knowledge is a characteristic that unifies science fiction, horror, fantasy and its siblings. For instance, Science fiction may base its premises on proven scientific knowledge (epistemological knowledge). Still, once this scientific knowledge is extrapolated for the worldbuilding of a story, then it becomes ontological. For instance, films like Deadpool (2016) and Lucy (2014) are based on our scientific knowledge that some substances can unleash extraordinary strength in human beings (say, cocaine). This proven knowledge is now within the human intellect; therefore, it constitutes epistemological knowledge. However, once this epistemological knowledge is extrapolated into the worldbuilding of the two films to speculate on what could happen if a larger amount of such a powerful substance were injected into an individual’s body, assuming the individual survives, it becomes an ontological question, one that transcends the domain of the current human epistemology. It is this characteristic of ‘ontology’ that science fiction shares with fantasy and horror. For instance, horror movies with a religious background, like The Pope’s Exorcist (2023), claim to be based on a real-life accounts. Still, it remains speculative because the existence of the devil lies beyond human epistemological knowledge, and therefore, ontological. Thus, any text that deals with what is currently provable within human intellect or our everyday reality is considered a form of realism.

Defining texts through the lens of epistemology and ontology to differentiate between realist and speculative texts, and using that framework to map out the texts I read in the book, was extremely helpful to me in writing my book. This is because many Nigerian writers, such as Akwaeke Emezi and Chigozie Obioma, are not happy to be called speculative writers, as they argue that their worldbuilding is not made up, unlike Tolkien’s in his books, but rather based on reality from the viewpoint of their own cosmology. What a defining speculative text from the lens of ontology helps me do is to respect the Igbo culture from which it is written. Yes, their texts are based on the reality of their culture, rather than being made up, like Tolkien’s world. However, as long as the explanation of reality in their texts extends beyond the current human episteme, it falls within the realm of metaphysical knowledge. Thus, that knowledge is ontological and therefore part of a speculative tradition.

This formulation is not just applicable to African literature, but also to Western fiction. For instance, those within Christian cosmology see the existence of a devil as a reality. Even though the devil is a reality to people within Christian cosmology, it is an ontological concept because it lies outside the current human episteme, which encompasses things that can be explained within the human intellect. To say that texts like Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater (2018), which is based in Igbo cosmology, are ontological texts, like Tolkien’s, whose worldbuilding is made up, is not to equate both texts, but to map out their shared character as ontological texts. This character is important because it decentred anthropocentrism by showcasing knowledge beyond the current human episteme. Knowledge within the current human episteme is what humans can easily control; ontological knowledge, on the other hand, signals to human beings things beyond their control and invites humility. It is the decentring of humans that makes ontological texts necessary for discussing climate change, as they look beyond what humans are currently experiencing by centring on nonhuman experiences.

Uncredited cover for the 2018 1st edition

Furthermore, using the ontological character of text as a distinguishing feature helps me evade a problematic that has plagued and continued to haunt cultural studies in African and African studies at large. Following colonialism, which predicated itself among other things, the false claim that it is a bringer of western modernity, because African has no modernity. African and non-African intellectuals in African cultural studies and those in African studies have gone to work, and what they predominantly do is to excavate one or the other African epistemology or ontology and then use it to ‘write back’ to colonial ideology and posit that Africa has modernity. We see this influence in postcolonial studies, in decolonial theory, and it is undoubtedly at play in the theory of magical realism.

In regard to magical realism, in response to your question, to oppose colonial claims to modernity, what magical realism does is to excavate ontology in a text of non-Western, say, ogbanje in the novel Freshwater (I analysed Freshwater in the monograph). Magical realism employs ontology to demonstrate that Africa has a modernity that differs from Western modernity, thus showing that the colonial claim was false. Showing that Africa has modernity is not bad in itself; however, in doing so, magic realism as a theory has limitations on the text, and that is that it elides the ontological perspective of the text, which characterises its speculative property. For magical realism, this ontology represents a form of realism from non-Western cultures, one that showcases non-Western modernity in contrast to the European claim to modernity. For instance, an analysis of ‘Freshwater’ as a work of magical realism will not pay attention to the futurism of transgender subjectivity that the text foregrounds, and this is what I was pointing out in my book by showing that a sole focus on colonialism in analysis in African studies is doing a lot of harm. On the surface, this harm will not be discerned easily.

3. Before we dive into more specific works and historical contexts, what is the big takeaway you want readers to leave with after finishing your book?

The key takeaways of the book are that Nigerian Speculative fiction has a long genealogy. However, its proliferation was impacted by the focus of writing/literary studies of Nigerian fiction on colonial discourse due to CIA influence on the canonicity of Nigerian literature. Further, this current dominant way of reading African literature from solely the perspective of colonial impact is a cultural violence.

Cover for the 1990 edition of Kojo Laing’s Woman of the Aeroplanes (1988)

4. For those new to older Nigerian SF (like myself), what are one or two works published in the 80s or earlier that you recommend new readers check out?

Buchi Emecheta’s The Rape of Shavi (1983) is a good one. The Ghanaian [B.] Kojo Laing is not a Nigerian. Still, his Woman of the Aeroplanes (1988) is another notable work from the 1980s, particularly if you are considering African speculative writers in general. Earlier works of Nigerian speculative writers include D. O. Fágúnwà’s Forest of a Thousand Daemons: A Hunter’s Saga, trans. Wole Soyinka (1938), and Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952). I consider these to be the foundational texts, and they are a good place to start.

Cover for the 1950 edition of D. O. Fágúnwà’s Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmọlẹ̀ (1938)

5. What hampered the evolution and proliferation of Nigerian SF in the twentieth-century?

There are a few theories about the evolution and proliferation of Nigerian SF. In the book, I examined these theories. For instance, some theorists argue that economic poverty in the country hindered the proliferation. As such, writers are more interested in responding to these financial issues than in writing about robots or aliens. In the book, I presented the strengths and the weaknesses of these arguments before adopting a stand. The stance I took is that what limited this proliferation is the way ‘writing back’ was used in the history of African literature.

6. I am deeply obsessed with the interplay between the Cold War and literary production. As you mention, President Eisenhower proclaimed in a 1952 campaign speech “our aim in the Cold War is not conquering a territory or subjugation by force… our aim is more subtle, more pervasive, more complete” (63). In the process of Nigeria’s independence from the British Empire (1960), the United States took on an active role in the continent. The CIA looms large in your analysis of Nigerian canon. What was its role? What did it seek to achieve? How?

There is, of course, the opportunity that the American Empire saw in the 1950s, with the decolonisation movement underway and the British Empire on the verge of extinction as an empire. While the American Empire sought to assume the role of the British Empire, it recognised that this wouldn’t occur through the same method employed by the British Empire, which involved the outright use of naked force. It is from this mindset that President Eisenhower formulated his covert policy.

Specific to art, it was led by the CIA while using the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) as its front. The CCF, through its sponsorship of artists and conferences, utilises the politics of visibility to establish the canon of Nigerian literature. Researchers studying this period often disagree on what the CIA achieved, as some argue that the CIA ended up wasting their funds because the writers involved did not know at the time of receiving the funds that the CIA were involved, so more or less, they wrote what they would have written if the CIA were not involved. However, in my book, I argued otherwise and assert that the CIA were quite successful and that they achieved their aim. Part of their ambition is to sell the American Empire as a benevolent entity, not a benign one. So, for instance, where it will be almost impossible to get a Nigerian writer, say Achebe or Soyinka, to write in the praise of the American Empire, CIA influence on the canonicity of Nigerian literature ensured that the focus of the canon is solely on the criticism of the British Empire, whose power American Empire is gunning for. For the CIA, their support to these writers is a kind of enemy of my enemy is my friend sort of thing and thus should be supported.

The canon of Nigerian literature ultimately consisted of texts criticising the common enemy of both Nigerian writers and the American Empire: the British Empire. Ultimately, there are no outright praises for the American Empire in the canon enabled by the CIA in Nigeria, but there is also little negative PR. This should be considered a great win for the Empire, which was exploiting but receiving relatively little or no negative PR.

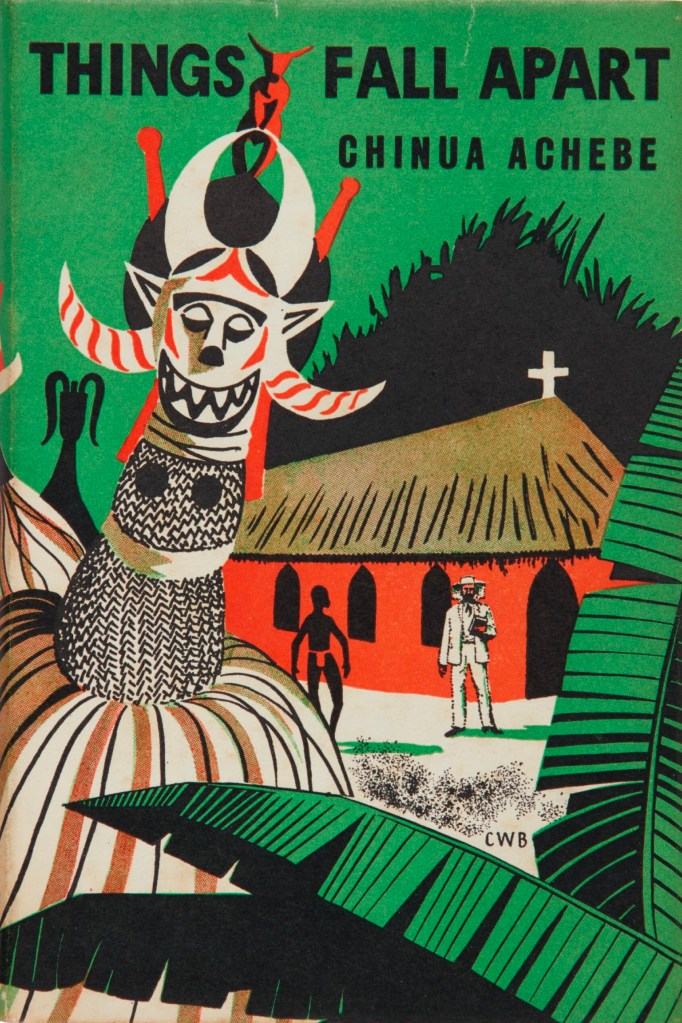

C. W. Bacon’s cover for the 1st edition of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958)

7. Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) is the African literature touchstone for so many Americans. I have powerful memories of reading it in my 9th grade English class in rural Texas. I must confess my utter ignorance until I read your book about its role in establishing a pattern of postcolonial literature that directly and indirectly excluded so many other voices (the Négritude movement for example). You describe it as “the master template of the CIA-enabled literary canon” (71). Can you discuss a bit of the controversy around the novel?

I think that I can share with you that the text is an excellent work of art. However, regarding its current place in the canon of Nigerian literature, I doubt that if canonicity was not overly influenced by the CIA, we would have it in the same place. Without that influence, Nigerian literature would have been quite diverse; Things Fall Apart would still be a great novel, but not the novel that the entire canon of Nigerian literature mirrors as its template.

I must admit that I didn’t detect this pattern or controversy around the novel earlier in my life, apart from the fact that my elder brother once pitched the text against Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard as I have pointed out in the answer to the first question of this interview. When I began to realise that something was wrong with the way the novel is positioned, it was during the research for this monograph, especially about the canon of Nigerian literature. A clear pattern began to emerge that shocked me. First, the support Achebe received from the CIA, such as being a part of the Makerere Conference in 1962. For proper context, the Makerere conference is so influential in defining, essentially, almost all the parameters of what is currently considered the canon of Nigerian/African literature (I am paraphrasing critics like Mukoma Wa Ngugi and Peter Kalliney on their take on the Makerere conference). Then when I carried out a further scrutinising of the novel itself in the monograph, it reveals perplexing details in the structuring of the novel which for sure benefits American Empire: the critique against British Empire, writing back, advantage of English language in language politics in Nigerian literature, colonial discourse as an argument about cultural difference etc fit into the topoi of the novel.

8. What were the defining features of the Nigerian SF voices left behind in canon formation?

Ecocriticism, animist ethics of familyhood and critique of capitalism.

Cover for the 2013 edition of D. O. Fágúnwà’s Forest of a Thousand Daemons: A Hunter’s Saga, trans. Wole Soyinka (1938)

9. You describe D. O. Fágúnwà’s Forest of a Thousand Daemons: A Hunter’s Saga, trans. Wole Soyinka (1938), with its shape-shifting flesh-consuming monsters, as an early speculative take on “animist ethics.” How does this connect with a critique of capitalism in the novel?

D. O. Fágúnwà’s Forest of a Thousand Daemons: A Hunter’s Saga was quite focused on animal ethics, specifically suffering, intersubjectivity, and the entanglement of humans with animals. This was influenced by animist ethics in Yoruba cosmology, from which D. O. Fágúnwà writes. What is interesting about this text is that in the current world and even the immediate generation after the text publication, it is still relevant and that is why I paired its reading to Derrida’s thesis of animal suffering and trace its similar idea to the contemporary time in the essay of Charlie LeDuff’s “At a Slaughterhouse, Some Things Never Die” (2000). These varied periods and different localities allowed me to connect the novel, showing that the continual suffering and subjugation of animals throughout these periods and localities stem from the capitalist ethics of profiteering, and that the same ethics also crush us. Essentially, kindness to animals leads to a different ethical system where we are kinder to one another, and this system of empathy and compassion is not what capitalism can offer.

Barnett Freedman’s cover for the 1st edition

10. Of all the Nigerian SF works excluded from the canon you cover, Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952) jumped out to me as it contains overtly speculative, and utopian, explorations of various economic and social systems. The novel was reduced to “nothing more than an anthropological text” amongst Western critics (104). Why was the novel controversial and subversive?

What made the novel so controversial at the time of its publication was that it was misread. A lot of African critics don’t like the novel when it was published citing its usage of what they consider poor English grammatical expressions. However, the complaint about the grammar of the text is based on the feeling among predominantly African critics that the novel helps the West to assert its logic of calling Africans premodern. On the other hand, many critics from the West like the text because they tend to read the novel as the original premodern thinking of a Yoruba person that has not been influenced by Western ideas. So, critics from both sides of the pond were entangled in their argument about premodern/modern logic, which they used to frame the novel. This is essentially an anthropological reading of the novel, presented by both sides, albeit in opposition to each other, which has made the text highly controversial. However, the text didn’t fit the model and resisted an anthropological reading.

In the monograph, I employed a proper tool of speculative fiction analysis to demonstrate the tradition to which the novel belongs, the misreading it has endured, and how it has subverted these impositions of anthropological reading that were forced upon it, starting from its acceptance for publication by Faber and Faber.

Joey Hi-Fi’s cover for the 1st edition of Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon (2014)

11. You devote multiple chapters to the growth of Nigerian SF—represented by authors such as Nnedi Okorafor, Tade Thompson, Akwaeke Emezi, etc. What lead to the “renaissance” of the speculative genre in Nigeria? How do they move beyond the paradigm of “writing back”?

The challenge for any writer is the platform. This worked against Nigerian writers who were not ‘writing back’ for a long time until the advent of digital technology liberated them. Due to this digital liberation, we can read themes that would not typically be published because of the gatekeepers’ addiction to publishing texts that ‘write back’. These emerging texts now explore various themes, including futurist, onto-ethical, animal ethics, and disability themes, among others.

12. What are your next projects?

I am researching Afro-gothic to write a monograph. Also, I am involved in a project led by Polina Levontin, Onesmus Mwabonje, and Jo Lindsay Walton on Applied Science Fiction. We are curating a toolkit and original short stories, accompanied by an essay.

Thank you so much for your answers. Good luck with your future projects!

Thanks so much.

Taj Ahmed’s cover art for the 1963 edition of Wole Soyinka’s play A Dance of the Forests (1960)

Notes

- Relevant previous posts: Interview with Jaroslav Olša, Jr., author of Dreaming of Autonomous Vehicles: Miles (Miroslav) J. Breuer: Czech-American Writer and the Birth of Science Fiction (2025); Interview with Jordan S. Carroll, author of Speculative Whiteness: Science Fiction and the Alt-Right (2024); Interview with Adam Rowe, author of Worlds Beyond Time: Sci-Fi Art of the 70s (2023); Al Thomas’ “Sex in Space: A Brief Survey of Gay Themes in Science Fiction” (1976); and Sonja Fritzsche’s “Publishing Ursula K. Le Guin in East Germany” (2006). ↩︎

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

This was a great interview. Thanks for sharing it!

Thank you for stopping by! I hope you wrote down a title or two to track down. I certainly have.

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 7/21/25 Weightless Weightless…Don’t Scroll Me! | File 770

Interesting topic. Great blog.

Thank you. Interested in any of the works he covers?

Every time I read about Afrofuturism or new African SF (Speculative fiction), it reminds me my visits to Nigerian bookshops in the 1990s, where I have found quite a number of interesting science fiction. Not the highest literary quality but an interesting view into emerging genre literature. Did they influenced today writers?

I am going to buy the book, but at least I want to mention a couple of interesting early SF books from Nigeria, such as: Tunde Omobowale: The Melting Pot, Lanna Solaru: Time for Adventure, or a series of near future political thrillers by Agwuncha Arthur Nwankwo.

Sorry for messing it up. Author of the previous comment is Jaroslav Olša, Jr. – olsa-jr@post.cz

No worries. Thanks for stopping by! I’ll have to look up some of those books. I must confess I learned a ton reading this monograph. As I indicate in the review, beyond the most basic Nigerian works, I am completely ignorant.