Today I’m joined again by Rachel S. Cordasco, the creator of the indispensable website and resource Speculative Fiction in Translation, for the seventh installment of our series exploring non-English language SF worlds. Last time we covered Izumi Suzuki’s disturbed shocker “Terminal Boredom” (1984, trans. by Daniel Joseph 2021).

Please note that Rachel and I are interested in learning about a large range of authors and works vs. only tracking down the best. That means we’ll encounter some stinkers. This time we have an interesting German-language tale of ecological dystopia from Austria.

You can read Herbert W. Franke’s “Slum” (1970, trans. by Chris Herriman 1973) here if you have an Internet Archive account. This is an six page story. It’s really hard to talk about it in any substantial way without revealing spoilers.

Thank you Cora Buhlert for the recommendation!

Enjoy!

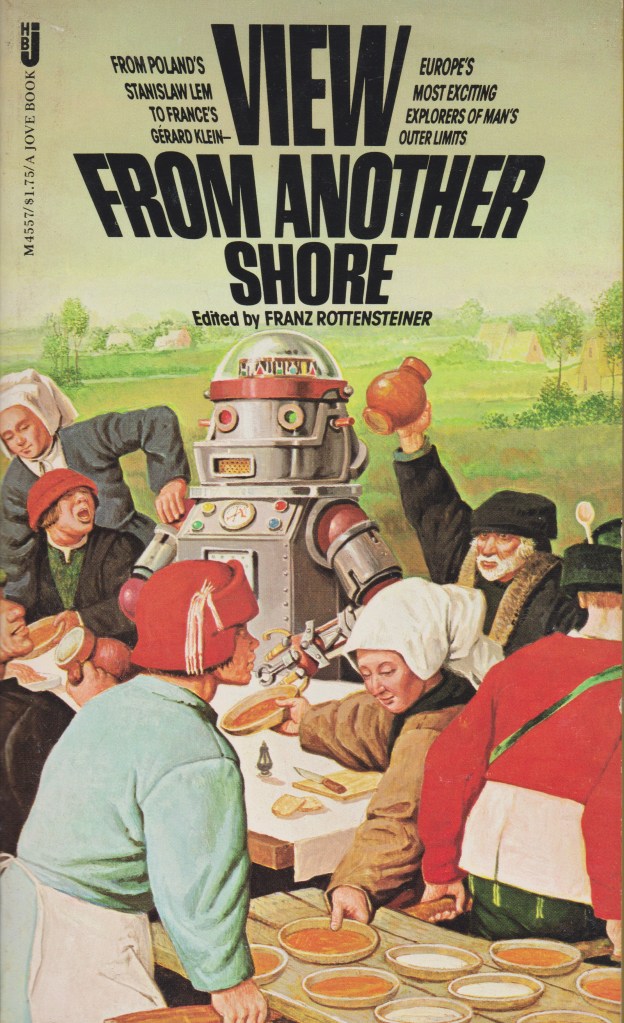

Gianni Benvenuti’s cover for the 1978 edition

Rachel S. Cordasco’s Review

Austrian-born author and cyberneticist Herbert W. Franke used speculative fiction to imagine distant planets and alternative societies for over half a century. Known to Anglophone readers mostly for three novels translated in the 1970s (The Orchid Cage, The Mind Net, and Zone Null) and a few short stories, Franke asked readers to think through what “exploration” really means and the responsibilities that the explorers have to those whom they find (or don’t find). Appearing first in English in F&SF (1963), Franke was subsequently featured in Franz Rottensteiner’s three major SFT anthologies: View From Another Shore: European Science Fiction (1973),The Best of Austrian Science Fiction (2001), and The Black Mirror and Other Stories: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Germany and Austria (2008). Other Franke stories appeared in Donald A. Wollheim’s The Best from the Rest of the World (1976) and James Gunn’sThe Road to Science Fiction 6: Around the World (1998).

The story under consideration today, “Slum,” shares with Franke’s translated novels a plot centered around humans discovering an alien civilization and attempting to understand it. In The Orchid Cage, for example, the explorers have to figure out why a mechanized city on an Earth-like planet was abandoned. “Slum” begins by asking us to assume that the “expedition team” is returning from another planet, but it is only much later in the story that we learn that this isn’t the case. One particularly interesting note about the first paragraph is how it channels the crime drama Dragnet airing on US television in the 1950s and 1960s (“Just the facts,” the chairman of the Commission demands from the expedition team). According to Gundolf S. Freyermuth in a Medium article on the topic, the Dragnet franchise, which had begun with radio broadcasts in the 1940s in the US, was adapted for TV in West Germany in 1957 (and was quite popular). So why would Franke open a science fiction story as if it were a crime drama? Perhaps to heighten the tension, or more likely, to signal that, despite what one would expect from a Franke tale, this particular one is very firmly set on Earth.

Structured as an interrogatory dialogue, “Slum” slowly unfolds the story of an expedition team asked by the Institute for Ecological Research to find out why the “outer air” had changed and why the bacteria count was up. Soon we learn, through Govin (a member of the team) that humanity had thought that “the outside world was dead. After all, it’d been years since anyone had left the suboceanic cities.” Over a decade later, French-Canadian author Elisabeth Vonarburg would explore a similar situation (The Silent City), where humanity has retreated underground following an ecological disaster, assuming that nothing above ground is left alive (only to find out a century later that they were very wrong). Following the chairman’s instructions to give “just the facts,” the team carefully explains exactly what happened after they reached the surface: they took fully-loaded vehicles that would allow them to explore in comfort and safety. At first, all they saw was ruin: garbage, dust, fog. Then rats. That’s when the team first started to doubt what they had been told about the surface—the rats were actually fat, as if they had been eating well, suggesting that the surface was not dead at all.

Spliced into the story are glimpses of a videoscreen showing a young girl playing with stuffed animals and candy wrappers. But the team ignores the girl, telling the commissioner about the string of bad luck they had soon after setting out across the ruinous landscape. One of their vehicles falls into a pool of sulphuric acid, they detect a gamma radiation field near their site, a crocodile-like creature drags off one of the team members, a fire breaks out, a building collapses suddenly, etc. The team members keep chalking everything up to natural causes until one of them hears crying. This is where the girl comes in—a team member discovers her being beaten by a man, but when he tries to help her after the man runs off, she scratches him and tries to get free. When the team takes the girl and tries to get back to their one remaining vehicle, the “men in rags, freaks and cripples with ugly faces” chase them and try to stop them from escaping. One of them shoots and kills an expedition member. Not long after, the team is retrieved and brought back underground.

As Petrovski, one of the team members, then asks, “ ‘what now?…Those are human beings out there, and we were never even aware of their existence. They must be the descendents of the ones who didn’t emigrate—the ones who chose smog, filth and pollution over the purity of suboceanic life.’” To this, the commissioner asks “ ‘is it our duty to help them?…Should we take them in, open our safe, hygienic world to them—to others like that little girl?’ ” The ultimate question then is asked without being attributed to any particular character, the narrator seemingly putting it directly to the reader: “Where did their responsibility lie? Out there? Or with those inside?”

One can detect a kind of simmering contempt on the part of the narrator…for the sanctimonious expedition members. Petrovski’s use of the word “purity” suggests that he can’t even conceive that any lifestyle other than his own would be desired. The girl herself, as the story tells us, fought as hard as she could to stay where she was, even though she was very young and being beaten by someone who might have been her father or older brother. The team (what’s left of it) asks itself if it should “help” those who have been living on the surface, despite the fact that those surface dwellers did everything they could to drive off what they considered intruders (not the kind of attitude someone would have if they wanted to be rescued). Assuming that their underground civilization is superior, the team members sit around wondering if they should share their bounty with the surface civilization, as if the latter would even want it.

The story’s title itself makes it abundantly clear that Franke is asking his readers to think about their own assumptions when it comes to city-dwellers and slum-dwellers in our own civilization. Is it pure selflessness for the wealthy and well-to-do to move those from the slums away from their homes, just because the former thinks it would be good for the latter? Who gets to decide what is best for whom? Which brings us back to the first paragraph…perhaps Franke’s channeling of Dragnet and its self-described attempt to treat events with the cold eye of objectivity is highly ironic, suggesting that, just as we cannot know what is “best” for others, we cannot remain objective when it comes to our assumptions about the value of our own lifestyles.

A selection of X Magazin issues

Joachim Boaz’s Review

3.5/5 (Good)

Preliminary Publication note: Herbert W. Franke’s “Slum” (1970, trans. by Chris Herriman 1973) first appeared in English translation in View from Another Shore, ed. Franz Rottensteiner (1973). I’ve been unable to track down the exact original location of the German original other than a 1970 issue of X magazin under the title “In den Slums.” The View from Another Shore anthology contains one of my absolute favorite non-English language short stories: Lino Aldani’s “Good Night, Sophie” (1963). I look forward to working my way through the rest of the stories!

The Institute for Ecological Research sends out a team from humanity’s underwater cities to explore Earth’s surface after detecting a “change in the composition of the outer air” (118). The survivors of the expedition relay their story to the Office of Investigation. Looming over the interrogation is a giant videoscreen with an unusual scene: a young girl playing with “colorful foil-wrapped bonbons,” which she furtively hides behind stuffed animals (117). The details unfold in a dialogue between investigators and the members of the team: we learn of the decaying human-made world above, the huddled survivors and their decrepit rituals of survival, and a profound question of morality and our responsibility for our fellow humans.

The story’s ending hints at the implications for the lives of those who fled the destruction above. Franke suggests the Earth is an integrated system, we cannot hide from the impact of pollution. We cannot hide in bunkers or under the ocean. Human transformation of the planet will introduce set of moral questions that are all too easy to dismiss by those who manage to survive in relative comfort “not our problem.” While some might critique Franke’s vision as a bit on the nose, despite global warming’s overt impact on our daily lives too many of us shrug it off in a similar manner.

An interesting little vignette told in a detached pseudo-scientific manner, that suggests a macro-ecological unity and the inability to escape the environmental devastation we unleash on our planet. I look forward to tackling a more substantial Herbert W. Franke work like Zone Null (1970, trans. Chris Herriman 1974). Somewhat recommended for the average fan of 1970s SF. If you have an interest in SF commentary on the ecological impact of humanity on our world, track this one down.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Nice to see another entry in this review series! Once again I am totally unfamiliar with this author, sounds worth investigating. The particular plot structure as described sounds like a classic Twilight Zone, what with the twist (they’re actually on Earth!) and the posing of an unnerving ethical quandary.

Thank you! As you know, we enjoy exploring lesser known territory. Unlike other authors in this series with very few translated works, multiple of Franke’s longer novels were published in translation in the US. As I mentioned, I can’t wait to read Zone Null.

I’ve never seen a Twilight Zone episode! Shocking? Perhaps? Hah.

yeah I’m gonna see if I can track down some of his translated novels.

I’m sure there’s no point in my proselytizing about Twilight Zone, you’re no doubt aware of its pedigree and connections to sf writing lol

I also recommend tracking down this anthology. It contains one of my favorite ever short stories in translation — Lino Aldani’s “Good Night, Sophie” (1963, trans. 1973) https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2022/01/22/the-media-landscape-in-science-fiction-short-stories-lino-aldanis-good-night-sophie-1963-trans-1973/

Pingback: Herbert W. Franke at SF Ruminations – Speculative Fiction in Translation