Graphic created by my father

In an August 1967 editorial in Galaxy titled “S.F. as a Stepping Stone”, Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) voiced his extreme disapproval of the New Wave movement as “‘mainstream’ with just enough of a tang of the not-quite-now and the not-quite-here to qualify it for inclusion in the genre” (4). He concludes: “I hope that when the New Wave has deposited its forth and receded, the vast and solid shore of science fiction will appear once more and continue to serve the good of humanity” (6). The implication is clear: there is an Platonic science fiction form that exists (and that he writes) that must be rediscovered.

Fellow “classic” author Clifford D. Simak (1904-1988) offered a different, and far more inclusive, take at his Guest of Honor speech at Norescon 1 (Worldcon 1971). In an environment of “shrill” disagreement between various New Wave and anti-New Wave camps, Simak celebrated science fiction as a “forum of ideas” open to all voices (148).

Preliminary note: I read the speech in Worldcon Guest of Honor Speeches, ed. Mike Resnick and Joe Siclari (2006). You can listen to the speech (at the 28:00 min. mark) here. For a wonderful range of photographs of Simak at the convention, check out this indispensable photo archive.

As I did with six Simak interviews earlier this year, I will paraphrase his main points and offer a few thoughts of my own.

Let’s get to the speech!

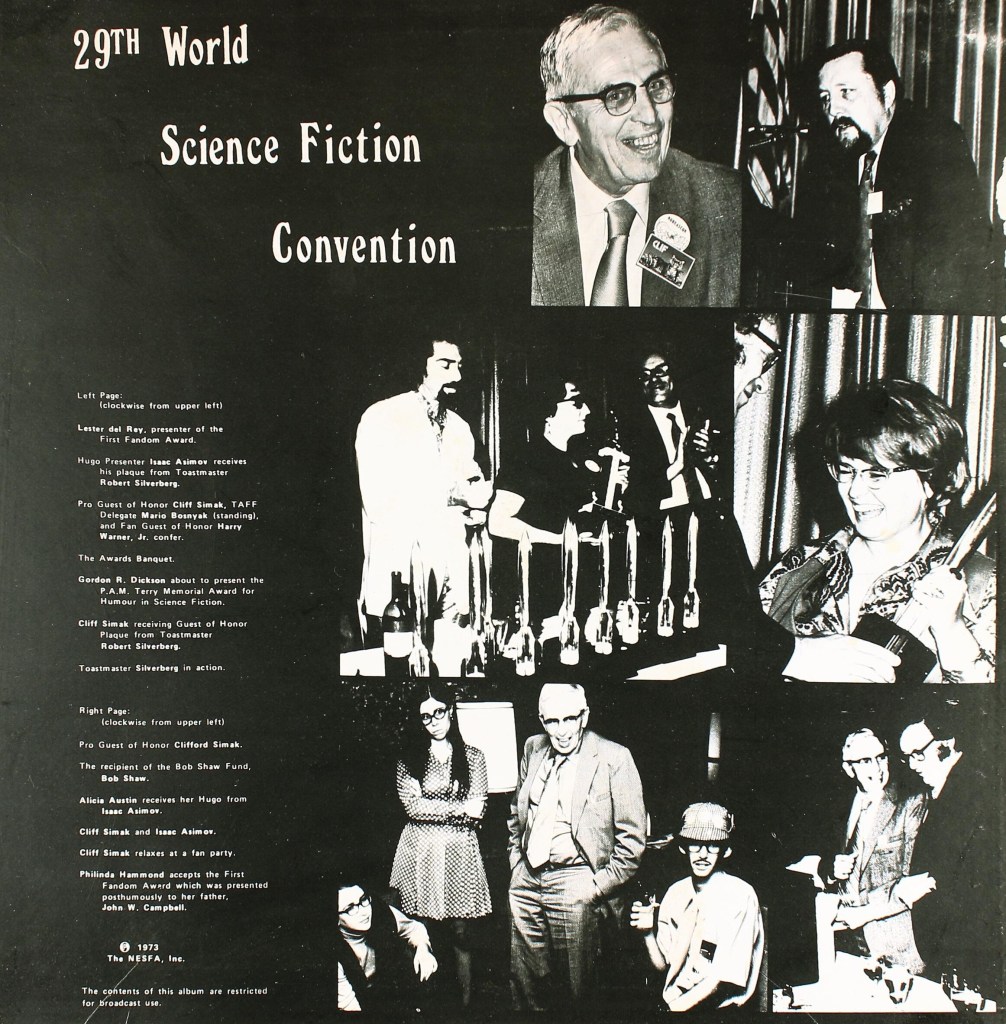

Jay Kay Klein’s photograph of Robert Silverberg, Clifford D. Simak, and Isaac Asimov at the 1971 Worldcon

After introducing his family (his son and daughter attended the convention), Clifford D. Simak surveys the general complains made against New Wave science fiction: “I have heard it said that science fiction has lost its sense of wonder; that too many bad stories are being written; that much of it is unreadable” (147). He points out that the effects of age might create the sense that contemporary SF lacks wonder: “The sense of wonder, my friends, was never in the stories, but only in ourselves. It is we, tired and jaded from having read so much, who have lost the sense of wonder” (147). While confessing that he does not understand all the stories published in that moment, he points out that there has always been awful SF — including stories that he wrote himself (147). He wagers that “if a panel of competent critics were to make a survey of science fiction through the years, they would find more praiseworthy pieces of fiction writing in the last few years than in any previous period,” including the “so-called” Golden Age (146).

The speech shifts to the “hopeful signs” represented by the current New Wave environment (148). He argues that the “old tradition” forged in the “thirties and forties” will be “enriched and strengthened” by new voices (148). He suggests the diversity of viewpoints shows that there “must be something viable and vital in the field to attract such talent” (148). In his most poignant and quotable moment, Simak argues that in order for science fiction to be a “forum for ideas,” it is essential that “it attract new talent” (148). He approves of the growing critical study of the genre.

In the following section he finally addresses the New Wave by its name and the controversy it has engendered. He argues that the movement “has become, or is in the process of becoming, a very important part of science fiction” (148). And that different interpretations of science fiction existing at the same time does not invalidate the other view: “we were faced by change and accepted it and made it part of us” (148). Science fiction’s great appeal has been its flexibility to engage with the new and controversy representing many points of view “is a healthy thing” as it shows the refusal to be complacent and demonstrates a deep care about the field (149). He bemoans the “shrillness of some of the controversy” emphasizes the big-tent mentality that there is room for all (149).

As Robert J. Ewald, in When the Fires Burn High and the Wind is From the North: The Pastoral Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak (2006), suggests, I think it might be worth interrogating Simak’s writing in the late 60s and 70s as a product (or a thread) of the amorphous New Wave. His novels, and interviews, would increasingly question the generic divisions between fantasy and science fiction. In the more permissive publishing environment of the New Wave moment, he would publish his own genre-breaking experiments such as The Goblin Reservation (1968), Destiny Doll (1971), and Out of Their Minds (1970). Ironically, the New Wave critic Asimov applauded Simak’s speech (see photo above).

I found Simak’s speech a refreshing and inclusive message. An author of the older generation who started writing in the 1930s steps up and defends the new as equally part of the multi-various generic edifice he helped construct. And in his own way, Simak would also participate in creating the new. Science fiction should, and must, be a forum for diverse ideas.

My other recent posts on Simak

Best Science Fiction Stories of Clifford D. Simak (1967)

Exploration Log 4: Six Interviews with Clifford D. Simak (1904-1988)

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Fascinating! I actually just started 'City' last night, my first Simak! An interesting mind, I look forward to hearing this speech and exploring the rabbit hole.

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

Thanks for stopping by!

If I’ve already said this, I apologize. I wrote about the first story–“City” (1944)–recently: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2024/08/18/short-story-reviews-clifford-d-simaks-city-1944-ogre-1944-and-spaceship-in-a-flask-1941/

And was in a podcast about the second installment — “The Huddling Place” (1944): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Ib8jqIANRA

@sciencefictionruminations.com I did not know. Thank you!

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

And again, if you haven’t already, my article “We Must Start Over Again and Find Some Other Way of Life”: The Role of Organized Labor in the 1940s and ’50s Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak is the most serious thing I’ve written about Simak. And I think is an original interpretation of some of his early short fiction — including the first installment “City” (1944) which I mention.

@sciencefictionruminations.com just finished the article. Well done! We often think of authors as people who don't exist unless they are scribbling away at our entertainment, the article was a nice placement of ideological context.

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

Glad you enjoyed it! I’ve read a bunch more 50s stories on organized labor and hope to eventually put together a larger more synthetic look at multiple authors on the theme. A pipe dream perhaps… we shall see!

@sciencefictionruminations.com

There is very much a lesson here for certain current groups that see the new new forms and writers as a threat to their status quo.

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

Thanks for stopping by. I agree.

Enjoy Simak? Any favorites?

@sciencefictionruminations.com

I find his writing to be excellent, but unsettling. This is not a criticism as such, more an observation. A bit like NZ cinema – The Quiet Earth, for example.

As for a favorite, I have always had a bit of a soft spot for Shakespeare's Planet.

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

Speaking of The Quiet Earth, I recently acquired Craig Harrison’s first SF novel — also set in NZ. Seems to speculate on racism towards the Maori. My recent purchase post with more about the book: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2024/11/09/updates-recent-science-fiction-purchases-no-cccxxxix-frank-herbert-alan-e-nourse-ann-maxwell-craig-harrison/

I have not read Shakespeare’s Planet yet. Definitely supposed to be a product of his later genre-bending period.

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 11/30/24 Dead Pixels Don’t Scroll Plaid | File 770

Admirable sentiments, not entitely unexpected given the idiosyncrasies in his own writing but still refreshing to see someone aging without becoming a reactionary crank.

That photo at the top is great – Silverbob cutting quite a dashing figure, very swinging haha

Yeah, Simak seems to be the consummate kind person. The grandpa everyone wishes they could have! hah.

Read Asimov’s initial editorial – which is not particularly harsh but is almost comically self-serving coming from a guy who had pivoted almost entirely to popular science writing by that point, and had never been particularly strong when it came to the nuts and bolts of fiction (plot, prose, character etc). But I also think his core premise that a strong scientific underpinning is related to the quality of a piece of sf is fundamentally incorrect.

It certainly wasn’t the cruelest thing I’ve heard said about the New Wave. For that, I’d probably need to look at the fanzines of Richard E. Geis in which a lot of that debate happened.

SF, the New Wave, etc. are large amorphous collections of tropes that evolve and change. But yes, I agree that it is “fundamentally incorrect” to ascribe a “strong scientific underpinning” as necessary to make something SF.

Sorry to be so late commenting. I just found this essay. I have posted links to it over on the the Clifford D. Simak Fan Groups board where a bunch of us dinosaurs hang out, reminiscing and lamenting the passing of the Jurassic.

No worries! Glad you enjoyed it.

I am far more proud of my much more substantial article that I wrote this year on Simak — “We Must Start Over Again and Find Some Other Way of Life”: The Role of Organized Labor in the 1940s and ’50s Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2024/09/13/exploration-log-5-we-must-start-over-again-and-find-some-other-way-of-life-the-role-of-organized-labor-in-the-1940s-and-50s-science-fiction-of-clifford-d-simak/

Many thanks for this feature. I would expect this of Simak. He seemed to have a rather gentle, conciliatory approach, in contrast to the polemical approach of many other SFF writers, whether on the left (Michael Moorock) or right (Lester del Rey) of the New Wave divide.

Hello Carl, thank you for the kind words

Did you see my much longer article on his accounts of organized labor in light of the political debates of his day? My title: “We Must Start Over Again and Find Some Other Way of Life”: The Role of Organized Labor in the 1940s and ’50s Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak

Yes, I read and enjoyed your piece on labour, but I’ll have another look.

I don’t have any specific items on hand by del Rey about the New Wave, but I’ve read that he was a severe and indeed rancorous critic of it.

And feel free to link something that Lester del Rey said about the New Wave!