Graphic created by my father

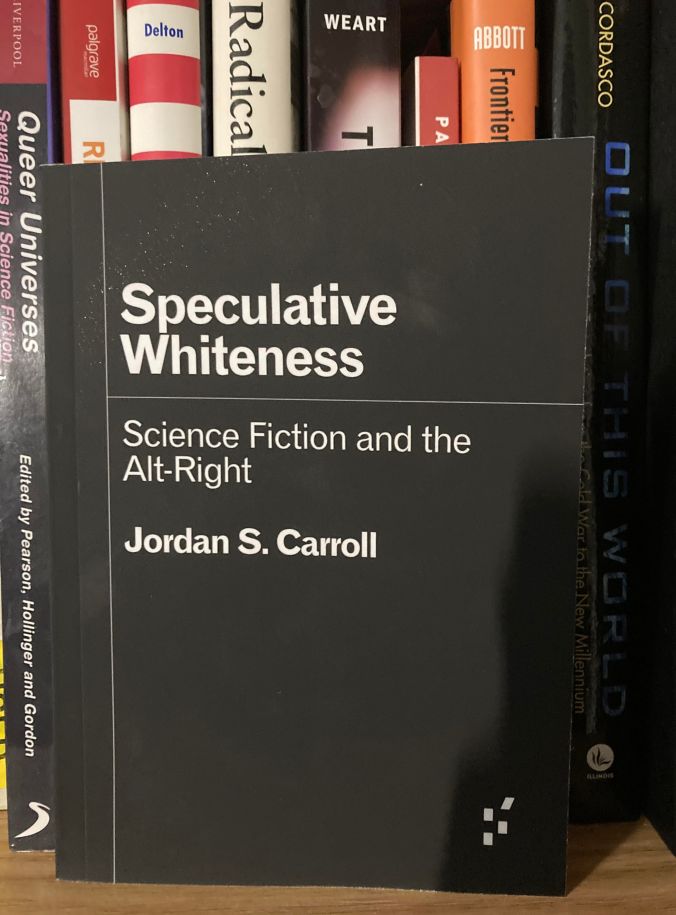

Over the last few years, I have attempted to incorporate a smattering of the vast range of spectacular scholarship on science fiction into my reviews and highlight works with my Exploration Log series that speak to me.1 Today I have an interview with Jordan S. Carroll about his brand-new book, Speculative Whiteness: Science Fiction and the Alt-Right (2024). In the book, he examines the ways the alt-right uses classic science fiction imagery and authors to mainstream fascism and advocate for the overthrow of the state.

You can buy an inexpensive physical copy ($10) directly from the University of Minnesota Press website or an eBook version ($3.79) on Amazon.

Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview. First, can you introduce yourself and research interests?

I received my PhD in English literature at the University of California, Davis. My first book was Reading the Obscene: Transgressive Editors and the Class Politics of US Literature (Stanford UP, 2021), and my latest book Speculative Whiteness: Science Fiction and the Alt-Right was just published by University of Minnesota Press. My work has appeared in a variety of venues including the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, American Literature, The Nation, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. I’m interested in a range of topics from censorship to science fiction, but all of my work deals with the relationship between politics and culture from 1900 to the present.

For clarity’s sake, what is your operative definition of “alt-right”? What is a specific illustrative example of its use of classic science fiction?

The alt-right is a fascist movement, which is to say an insurrectionary movement whose purpose is to overthrow the state in order to reassert what it perceives to be natural hierarchies, including hierarchies of race, gender, class, and religion.

The alt-right differs from previous fascist tendencies such as the White Power movements of the twentieth century insofar as it emerged out of places like blogs and imageboards. As a result, it adopted the spirit of irreverence, eclecticism, and disorganization that often characterizes those online spaces.

Perhaps more importantly for this project, though, the alt-right is primarily interested in mainstreaming fascism by winning culture wars. They often spread their message through cultural commentaries on genre films and literature, including science fiction. A typical episode of a Richard Spencer podcast involves spending an hour or more analyzing James Bond or Batman.

But even though the alt-right is something relatively new, coalescing during the Bush and Obama years, I argue in this book that it has antecedents in 20th century fan culture. The alt-right draws from a storehouse of science fiction images to make its points. Some alt-right partisans see themselves a superhuman mutants, for example, while others await the God Emperor foretold in Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965).

What inspired Speculative Whiteness?

I first got interested in the alt-right by falling down the rabbit hole of Nick Land’s blogs in the mid-2010s. I was interested in the question of how someone who seemed like “one of us”—an academic into stuff like cyberpunk—could become a total reactionary. This turned out to be the wrong question, though, because I realized that it was not incongruous at all. Throughout the history of fan culture, there have been fans who embraced racism and fascism. I began to better appreciate this after giving talks on H. P. Lovecraft and the Hugo Awards controversy, which I wrote as part of a project on how self-described geeks such as fans and computer programmers experience time. I therefore became interested in fascist nerds who claim a monopoly on the future.

Why do you think the alt-right is drawn to speculative fiction in lieu of other genres?

I should say that fantasy is as important in the history of US and European fascism, but I focused on science fiction in this book because it seemed like a more understudied aspect of the movement, perhaps because it is so counterintuitive. Fascism has always been a form of modernism: it promises a brand-new future that will be totally different from the present in important ways. Science fiction therefore provides a whole host of imaginative figures for this exciting new future (e.g., Nazis in space). Plus, science fiction is such a ubiquitous feature of cultural life post-Star Wars that it allows them to insert themselves into conversations where they otherwise would not be invited.

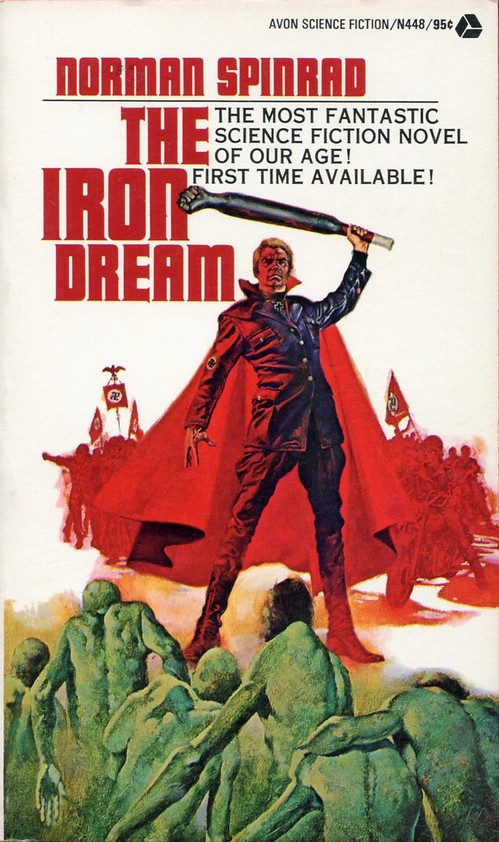

Uncredited cover for the 1972 1st edition

How does the alt-right engage with science fiction that’s critical of fascism and racism?

Often the alt-right reads science fiction against the grain. When they see fascism critiqued in texts like Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream (1972) or Star Trek: The Original Series’ “Space Seed” (1967) episode, they identify with the fascist ubermensch figure these texts present if only to condemn them. Richard Spencer loves Khan even if he hates Mr. Spock.

As you explain in the intro, science fiction can serve as a “blueprint, warning, forecast, wish-dream, and counterfactual” (8). How does the alt-right, as part of its interpretive project, reconceptualize the purpose of science fiction? Can it be self-critical?

The alt-right often sees science fiction as a prefiguration of the destiny that white men must realize. They have a very crude view of culture: it either moralizes or demoralizes white people. They’re therefore only interested in science fiction insofar as it either inspires them to greatness or stands in the way of their greatness. For all their sophistry, it’s a very crude way of thinking, one that precludes any kind of critical self-reflection or openness to the kinds of thought experiments that science fiction so often affords.

How is fascism connected with historical science fiction fandom?

We tend to think of fascists as outside agitators who are not real fans, but they have been here since the earliest days of fandom. The first major Neo-Nazi leader in the US was James H. Madole (1927-1979), who got his start in the science fiction community. In his writings describing the National Renaissance Party’s philosophy, he often drew upon science fiction images of a scientifically advanced cognitive elite who would rule the world and ultimately transcend their humanity to become “homo superior.” Instead of thinking of science fiction as inherently progressive, we need to think of it as an ongoing struggle between competing ideological tendencies. The left seems to be winning this war within literary science fiction, at least, but it was a hard-fought battle carried out over many decades.

As someone who wrote a PhD on issues of historiography, I am struck by your analysis of the alt-right’s perception of history both past and future. According to the alt-right, what is the connection between the two?

They see the future as recreating the past in a high-tech form. It’s what they call “archeofuturism.” Instead of imagining that the future is going to be radically different, they believe that it will emerge from racial or cultural principles that have always been inherent to Aryans for a millennium or more. As a result, they see the future not as building something new but as unleashing some preexisting racial potential that was previously expressed through cathedrals and so on.

For example, they often see space exploration as simply the latest manifestation of an innate white European desire to conquer and explore that drove settler colonialism. The upshot of this is that nobody who does not possess that idealized white European past can build the future.

It’s an anti-historical way of thinking about things, and it quickly devolves into obvious incoherence.

Robert E. Hubbell’s cover for the 1946 1st edition

A. E. van Vogt’s Slan (1940) and “other mutational romances” feature heavily in your analysis. You argue that mutants in these stories “tend to choose exit over voice, forming separatist enclaves or secret societies to pursue their interests without having to explain themselves to people who do not understand them” (34). What was the impact of Slan?

Slan provided fans with a myth that they were a persecuted but superior minority. Obviously, this arose partly out of a very real sense of marginalization and frustration with how fans were treated at the time. But it also helped set the template—along with Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged (1957)—that some people have special gifts that make engaging in democratic persuasion and dialogue with others pointless.

The enemies in many of the early mutant stories turn out to be the masses, who represent primitive throwbacks to the past when compared to the forward-looking mutant visionaries. The masses in these narratives are too irrational to be reasoned with — they have to be eliminated, avoided, or controlled.

Many writers of mutant stories in the 1940s were very self-conscious about this and tried to ward off the elitist or authoritarian dimensions of this idea, but it’s hard not to see it lurking in the background of fan culture. One fan even went so far as to claim that fans should develop a eugenics program to breed a superior race.

Are there any contemporary references to classic science fiction that you see as particularly dangerous?

I think there’s a growing fascination on the part of figures such as Elon Musk with science fiction narratives about smart men—and they’re usually men—who can see further than the rest of us and use that knowledge to change the world. We can see this in Musk’s love for Asimov’s Foundation series, obviously, but also his identification with the revolutionaries in Robert A. Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, who leverage their intelligence with the help of a supercomputer to predict the optimal way to overthrow the state and bring about a lunar libertarian utopia.

There’s also a burgeoning interest in combining this idea with eugenicist fantasies such as Idiocracy (2006). Techno-fascists seem to think that we need a high-IQ population to save civilization not only from existential risks such as hostile artificial intelligence or asteroid impacts but also the growing surplus population of low intelligent people who only think in the short term. This is an old idea in science fiction culture, simultaneously satirized and propagated in Kornbluth’s “The Marching Morons” (1952).

You indicate that one of the strategies for right-wing mainstream SF (Pournelle and Niven’s Lucifer’s Hammer, Heinlein’s Farnham’s Freehold, etc.) is to “racialize collectivism.” (48). Can you explain that phrase and its connection to the alt-right?

Collectivism has often been seen as a racial trait. We are told that some races are born conformists, while others are supposedly too incompetent to live without welfare provisions. Individualism, on the other hand, is often associated with white heroes who are too smart, too innovative, and too spirited to accept rule by the mediocre masses.

Often these masses are represented as racialized cannibals who want to devour the wealth and, ultimately, the bodies of white productive citizens. They’re worried that the poor are going to eat the rich. The alt-right is part of this same tradition. For example, many on the alt-right who are influenced by paleo-libertarianism argue that white people are best-suited for living in a free society. They therefore call for the “physical removal” of anyone who is genetically or culturally unable or unwilling to operate in a free market system.

John Schoenherr’s cover for the 1961 edition

How does the alt-right use science fiction to press for American supremacy in space? Why?

The alt-right loves space for a number of reasons. They see crewed space exploration as a symbol of national superiority, and as a result they view the pause in lunar landings as a sign of national degeneration and decline. Alt-right commentators often complain that money that could go to space travel is going to fund welfare programs for non-white people.

Furthermore, as I have suggested, they see space exploration as the fulfillment of the white pioneer spirit. The alt-right believes that white people possess a natural tendency to risk their lives to achieve glory.

Space is also especially appealing to them because it’s a place they can colonize without fear of mixing with an indigenous population. Space is strangely empty for the alt-right. Sometimes they imagine themselves as fighting the bugs from Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (1959), say, but usually they talk about space as a vast lebensraum where white populations can expand without any admixture or interference. They’re not interested in using science fiction to think about an encounter with the other.

Don Punchatz’s cover for the 1974 edition

Why has the alt-right embraced Dune (1965) despite Herbert’s suggestion that “our desire for science fiction saviors […] leads straight to totalitarianism” (73)?

The alt-right loves Dune partly because it represents that combination of archaic and high-tech that they see as their future destiny. They also identify with Paul’s willingness to take existential risks—to destroy himself and the entire spice trade—in order to achieve greatness. Furthermore, they believe that only an authoritarian leader such as a God Emperor can plan for the distant future. Democratic societies, they claim, think only in the short term because politicians have to satisfy the immediate demands of their constituents, who just want free handouts. Paul is great to them, then, because he is willing to ignore what anyone wants right now and even kill billions of people in order to eventually create a better society in the far, far future. This is what the alt-right wants: a prescient despot who will dominate everyone in the world to manifest his vision. Frank Herbert at least intended this to be somewhat of a cautionary tale about the power of charismatic leaders, but the alt-right is often willing to leave out aspects of the narrative or its context that are inconvenient to their readings.

What are your next projects?

I have started writing fantasy and science fiction. I have a short story forthcoming in Kaleidotrope, as well as a few more under submission. I also have a few critical projects in the pipeline, as well.

Thank you immensely for taking the time to answer my questions.

- A few relevant Exploration Log entries: My interview of Adam Rowe, author of Worlds Beyond Time: Sci-Fi Art of the 70s (2023); Al Thomas’ “Sex in Space: A Brief Survey of Gay Themes in Science Fiction” (1976); and Sonja Fritzsche’s “Publishing Ursula K. Le Guin in East Germany” (2006). ↩︎

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 1/6/25 We Have Top Fen Scrolling on it Right Now | File 770

I would have thought that science fiction authors always revealed non-fascistic views in their writings, which is not something that I would have thought would appeal to the far right. There have probably been things in SF such as those more superior succeeding over the inferior masses, but I think you’re usually made to feel sorry for them as being oppressed, rather than being the inherent right of a sort of Social Darwinism.

Hello Richard,

A lot of Carroll’s book explores those counterintuitive moments — i.e. how a work condemning fascism, like Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream, becomes a popular work among those circles. He wrote above and explores in more detail in the book: “Often the alt-right reads science fiction against the grain. When they see fascism critiqued in texts like Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream (1972) or Star Trek: The Original Series’ “Space Seed” (1967) episode, they identify with the fascist ubermensch figure these texts present if only to condemn them. Richard Spencer loves Khan even if he hates Mr. Spock.” Also, as the interview indicates, the alt-right’s interpretation of a work often shears it of authorial intention or simply ignores a more complex criticism.

He also addresses how those “mutational romances” can also be used by the left. Science fiction provides so many avenues for interpretation and reframing and reworking. He also addresses more recent explicit fascist science fiction works (often published by small fascist presses) that rework older ideas.

Hi Joachim. I see. It is ominous though, that such an extremist group have a lens to SF. They aren’t really interested in it, other than what appeals to their ideology, the content of which they warp to suit their own dark views. They don’t appreciate it’s literary value as most of us do and take it entirely seriously.

I definitely agree with that sentiment.

Great.

Posted a PKD review! I can’t remember if you mentioned this short story or not… it’s a good one.

I know. No, I didn’t mention it, but it is good. I’m going to reread it soon, before I comment, but I want to read the Tiptree one first. I think I read it in her collection “Her Smoke Rose Up Forever”. I’m going to go away and find out.

As always, I look forward to your observations!

It didn’t appear in Her Smoke Rose Up Forever. It did appear in Ten Thousand Light-Years from Home and various other best of anthologies.

https://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?41083

Thanks for posting, great interview on a disturbing (but not entirely surprising) phenomenon. You can trace these kinds of readings of SF back pretty far, I think, back to the 40s at least (and the establishment of the the whole white-man-conquers-space-aliens trope, which was usually just european colonialism writ large) if not even earlier. In terms of contemporary movements I am reminded of the meme about billionaire tech bros absorbing all the wrong messages from cyberpunk canon etc.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Carroll’s analysis definitely referenced John Rieder’s influential Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction (2008).

Damn, Boaz, this piece really is highbrow. Most of it was way over my head. Maybe you and Jordan Carroll should collaborate on a manuscript and submit it to the PMLA, perhaps for one of their ‘theme’ issues. Me, I’ll go find a copy of ‘Hustler’ magazine, slurp some Pabst Blue Ribbon, and ponder my affiliation with the Lumpenproletariat………….

This is not the first time you’ve said something to this effect. Obviously we all have our tastes. It’s a given. And that’s okay.

P.S. do you correspond with the Australian blogger and editor / author Andrew Nette, https://andrewnette.substack.com/ ? He routinely assembles books on pop culture / media culture, and for these, solicits essays from a large cast of contributors. These essays are ‘academic’ in nature and should be something you can provide quite readily ? Just a thought

Yes, he wanted me to contribute something on Malzberg for his SF volume. I declined as I was finishing PhD dissertations edits for final submission and starting a new job. I posted the introduction to Nette’s volume on my site a few years back. https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2021/11/21/updates-the-introduction-to-dangerous-visions-and-new-worlds-radical-science-fiction-1950-1985-ed-andrew-nette-and-iain-mcintyre-2021/

Pingback: Wow! Signal: January 2024 – Ancillary Review of Books

Dear Joachim,

Congratulations for this timely interview.

I have just contacted Robert S. Caroll for an interview for the Romanian mag Spectrul, but I imagine he must be quite busy at the time. My question is if I could translate this 2024 interview and republish it with you permission (and his) over here https://spectrul.ro/ . I am doing it as a fan (not payed for it) – and because i think Robert’s book just get the coverage in other languages as well. Let me know what you think. Thanks!

Hello,

I’ll reach out to Jordan. Definitely a deserving winner of the Hugo! I’m all for more academic, yet approachable, non-fiction getting the award.

Sincerely,

Joachim

Hi Joachim,

Thanks so much. Got your email, will do all of the required. Totally agree with with you and there’s a plethora of good new studies in that direction (including a new book by Ben Woodard). Will get back to you on the email.

best regards

ST

No problem! Glad it can reach new audiences.

Pingback: - Spectrul