Graphic created by my father

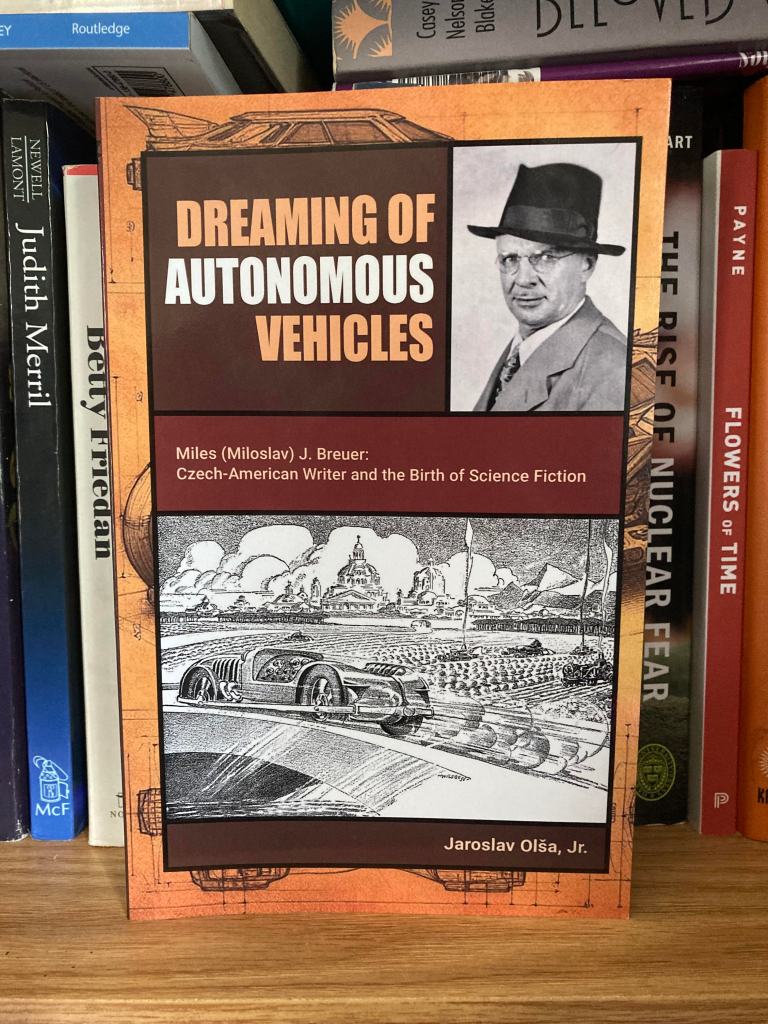

Over the last few years, I have incorporated a smattering of the vast range of spectacular scholarship on science fiction into my reviews and highlighted works with my Exploration Log series that intrigue me.1 Today I have an interview with Jaroslav Olša, Jr. about his brand-new book, Dreaming of Autonomous Vehicles: Miles (Miroslav) J. Breuer: Czech-American Writer and the Birth of Science Fiction (2025). In the book, he covers the life and career of Miles (Miroslav) J. Breuer (1889-1945), the first SF author to regularly write original stories for Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing. Breuer’s career also provides a fascinating window into the literary and cultural world of immigrants in late 19th and early 20th century America.

You can buy an inexpensive physical copy ($15.80 at last look) directly from Space Cowboy Books here (preferred) and on Amazon.

Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview. First, can you introduce yourself and your interests in science fiction?

Since childhood, I have loved reading science fiction, but — except for a short time — I have not been professionally attached to it. After studying Asian and African Studies and social sciences in Prague, Tunis and Amsterdam, I joined the Czech diplomatic three decades ago, and have served in various positions including Director of the African Dept. and the Head of the Policy Planning Dept. at the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I also served as a Czech Ambassador three times: to Zimbabwe for six years, to South Korea for another six years, and to the Philippines for four years. Since December 2020, I have served as Czech Consul General in Los Angeles in charge of the US West.

In the early 1980s, I became a part of a small but very active fandom when—in the then communist Czechoslovakia—the first science fiction club emerged. I started the SF fanzine Ikarie XB, which in 1990 turned into the first Czech-language professional SF magazine Ikarie, with monthly editions until 2024.

I have also translated many short stories and edited numerous SF anthologies, but never wrote fiction. But since the very beginning, the center of my interest in SF was to write about science fiction. I co-edited and authored entries in the only Czech SF encyclopedia, published in 1995. Thus my book about Miles (aka Miloslav) J. Breuer is somewhat of a culmination of my work on science fiction.

What drew you to the science fiction of Miles (Miloslav) J. Breuer (1889-1945)?

After finding out my next diplomatic post would be in Los Angeles, I wanted to find which SF authors were from the US West. In the 80s and early 90s, I was in close contact with Forry J. Ackerman (who even visited Czechoslovakia in 1990) but I have lost contact with the SF scene in Los Angeles around the year 2000 after I moved to Zimbabwe. So, in 2019, I started reading into it again, and I found that Miles J. Breuer died in Los Angeles. I knew very little about him as none of his stories were ever translated into Czech, but what sparked my interest was a small note on The Internet Speculative Fiction Database about his story “The Man Without an Appetite” which read: “first published in Czech in the Bratrsky Vestník about 1916″.

I was aware that Bratrský Věstník (aka Fraternal Herald) was an important Czech-language monthly published in Nebraska, one of the heartlands of “Czech” America, since the 1890s serving mainly as an information tribune to the members of a Czech life insurance company in the Midwest. I wondered, why would an American SF author be published in such a magazine?

Although the collections of Czech-language magazines published in the US are incomplete in Czech libraries, I found a few issues from 1916 and 1917 are part of the collection of the Czech National Museum. I wrote to the librarian in December 2019, kindly asking her if there were any stories by Miles J. Breuer, and received an answer a few days later that gave me goosebumps. She wrote that she did not find any records of “Miles J. Beruer,” but came across a story in Czech written by “Miloslav J. Breuer.”

I was utterly shocked. I then spent numerous days searching for more of Breuer’s work and discovered four more stories, all written in Czech but published in the United States. I knew I had to write about this discovery as I knew nobody in the US knew Breuer was not only Czech but wrote stories in Czech. And I knew for certain that nobody in the Czech Republic considered Breuer to be a Czech science fiction author.

Can you tell us a little bit about Breuer’s childhood, background, and early writing career?

Breuer’s father was both a medical doctor and a writer and translator who was quite adventurous, so the family and young Miles/Miloslav moved regularly. Until he enrolled at the University of Texas in Austin, lived and studied at numerous schools around Texas and Nebraska. He was much influenced by his father’s writings, as can be seen in his earliest piece of writing I discovered—a letter published in Czech when he was only in first grade. From then, he wrote frequently, but I could only find three short poems—all in English— published before he entered the University of Texas.

In Austin, he immediately joined local literary life and became a regular contributor as well as editor of UT’s literary monthly. As he published more than a dozen stories and even more poems there, it was clear that he could write swiftly. Though his first published piece—the letter from first grade I mentioned earlier—was in Czech, all but one of his early works until the mid-1910s were published in English. Many of his early works are unremarkable pieces, but interestingly enough, a significant number of them were genre stories, often horror stories.

I found your analysis of Breuer’s interaction with the larger immigrant Czech-American intellectual world absolutely fascinating. Can you say a few words about it?

Miles/Miloslav Breuer—as well as his father Charles/Karel and his brother Roland and sister Libbie/Libuše—were really living in two different worlds. They were integral parts of American society, but at the same time they kept their deep contacts with their Czech-American compatriots. It is not surprising, as Breuer for all his life—except for the last two or three years in California—lived in the places with a significant and influential Czech community. Nebraska is until today the US state with the highest percentage of inhabitants with Czech ancestry, and Texas has an incredibly active Czech community until now; the Texas sweets called “kolache,” based on the Czech “koláče”, are the most well-known sign of it.

This interaction with other Czech-Americans undoubtedly influenced Breuer´s writing career. He wanted to succeed in American literary circles—as he achieved—but working closely and being friends with editors of Czech-language periodicals in the US definitely influenced him to write in Czech.

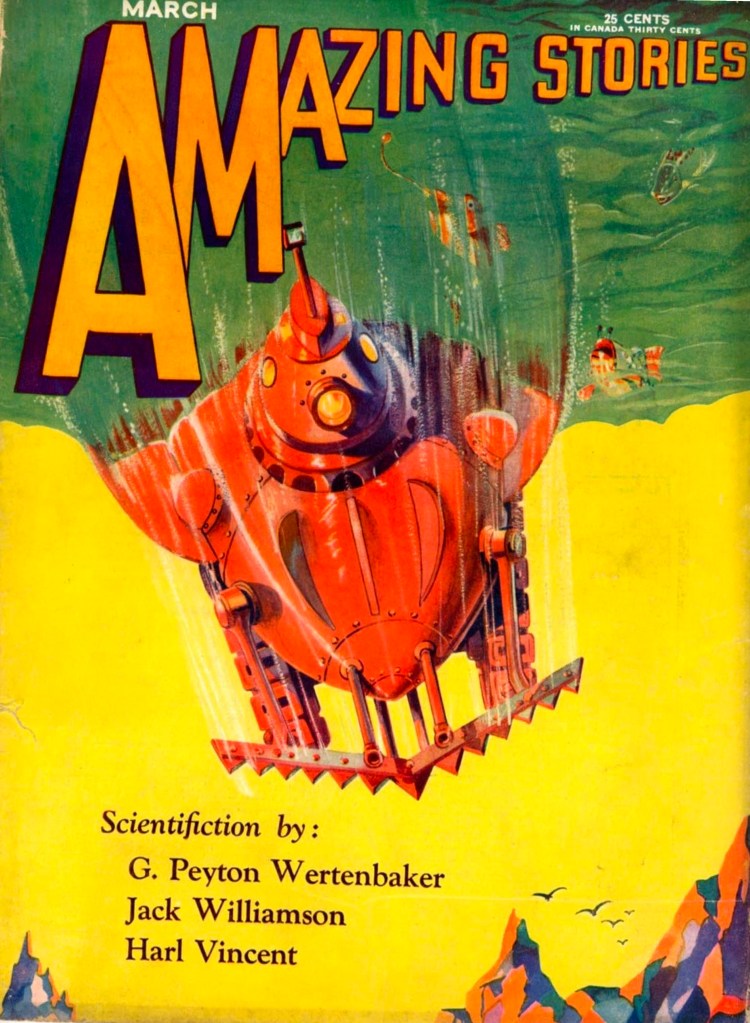

Leo Morey’s cover for Amazing Stories, ed. T. O’Conor Sloane, Ph.D. (March 1930)

Before we dive into the details of his fiction, what are two Breuer stories you recommend readers interested in the history of science fiction tackle?

Allow me to mention three stories, each for a different reason. The first one is “The Gostak and the Doshes” (1930) (in the March 1930 issue of Amazing Stories) (read online) definitely a tale that still has an important message today. It shows how fake news and media manipulation can change society—not for better but for worse, and that such fake news can even trigger war. This is probably the most mature of all Breuer’s stories. And one of only a few, which does not have either Czech or early English-language versions. It seems to me that this one was written originally for Amazing Stories.

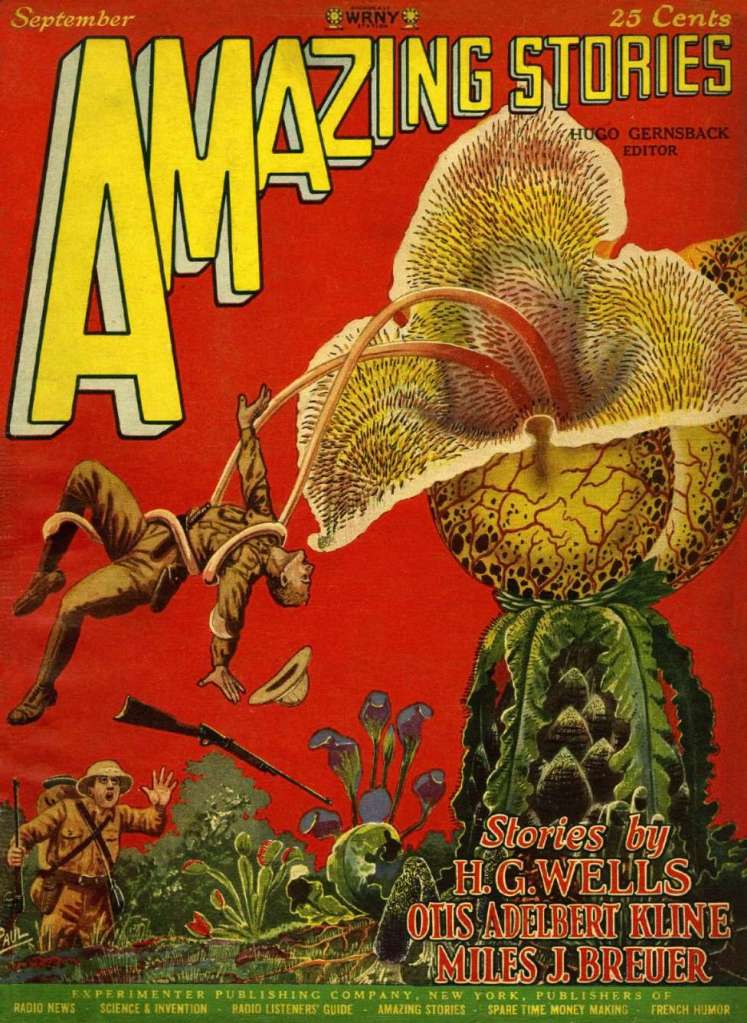

Frank R. Paul’s cover for Amazing Stories, ed. Hugo Gernsback (September 1927)

The second story I would like to mention is “The Stone Cat” (1927) (read online). It is definitely not the most remarkable piece of Breuer’s writing, but it is an interesting example of how Breuer was writing and rewriting his short stories. Breuer was well aware that he had to adjust his stories to the audience that would read them—and “The Stone Cat” shows it the most of all his works as we have three different versions of it. It was the fifth short story Breuer ever published as early as 1909 when he was twenty years old. Seven years later he published it in Czech in a slightly revised version, which was localized for the Czech-American community. While these two editions were not known until recently, all historians know “The Stone Cat” was published—in a very different version—in 1927 Amazing Stories—it was Breuer’s second story published there. In all the versions we see his literary development. This is not the only story which was rewritten and published during the span of two decades. When Breuer thought his idea was good, he was able to rewrite any story years later.

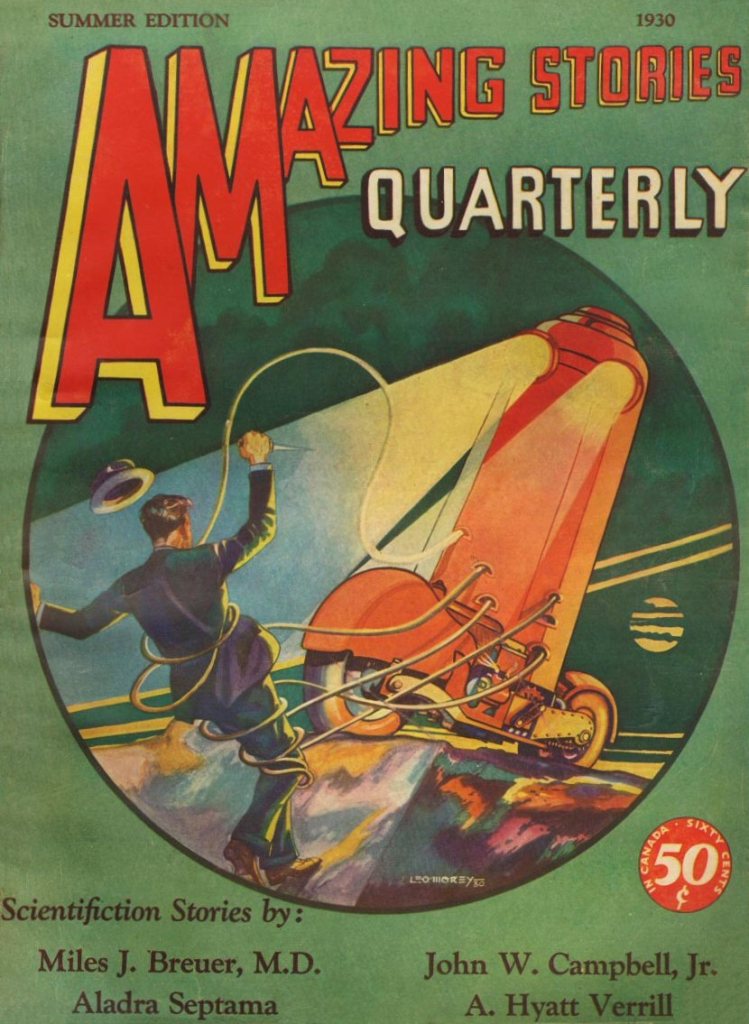

Leo Morey’s cover for Amazing Stories Quarterly, ed. T. O’Conor Sloane, Ph.D. (Summer 1930)

The third one is his famous novel Paradise and Iron published in 1930 (read online). It was originally published in Czech as Vyšší tvor in 1924 and two years later published in a non-literary magazine Social Science in English as The Superior Race. Both early versions were not known until recently. Paradise and Iron is quite an interesting work set in a futuristic world controlled by machines. It is one of the earliest science fiction stories where the writer urges caution when creating the new—“superior”—race, robots, or AI, which does not care about humans any longer. The expanded Amazing Stories Quarterly (Summer 1930) version is indeed more jazzed-up, it is heavily rewritten and expanded, which is significantly better reading. It also has a different ending. While in the early versions, the hero of the story escapes, in Paradise and Iron he fights the machines and wins.

R. W. Boeche’s cover for the 2008 1st edition

What were Breuer’s compositional methods? Who were his influences? I ask as your book, unlike other accounts of Breuer, explores how he rewrote earlier publications that originally appeared in Czech-language presses.

Breuer clearly stated that H. G. Wells was his source of inspiration. Much about this is in the excellent book The Man with the Strange Head (2008) by Michael R. Page, the first selection of Breuer’s short stories published in English. Thus I will not talk much about it.

What was interesting for me: was Breuer influenced by any Czech writer? Though we know Breuer was reading in Czech, there is not a single mention of any Czech writer in his writing known to me. Not even Karel Čapek, who coined the word “robot” in his famous drama R. U. R. which was published in Czech in 1920 and saw the first English edition only a few years later. And not only that, Čapek’s R. U. R. was extremely popular in the 1920s US. Is it possible that Breuer did not know R. U. R.? I doubt it—though Breuer never used the word robot in any of his stories even in the times when “robots” were already part of the tales published by Amazing Stories.

We know that Breuer wrote in both languages throughout his life, but there is no clear pattern that can give us the idea if he first wrote in English or Czech. We need more texts and information. As of now, we can only say that Breuer is the one and only Czech-American writer who wrote in both languages consequently.

You write that Hugo Gernsback desperately needed reliable authors for Amazing Stories. What was Breuer’s place in Gernsback’s magazines?

He was not only a prolific writer, but he was a real influencer, using today’s terminology. His more than a dozen contributions to the readers’ column in Amazing Stories were as important for the creation of modern science fiction as were the writings by Jack Williamson or Hugo Gernsback. Breuer´s 1929 essay “The Future of Scientifiction” (read online) might be regarded as one of the three most important manifestos of a new genre.

And—as I have already mentioned—he was also the very first “new” writer, who started contributing to Amazing Stories regularly. I would say that between 1928 to 1931 he was among the five most important science fiction writers in the magazine, and also among the most prolific. In these years he published some 20 stories, including two novels.

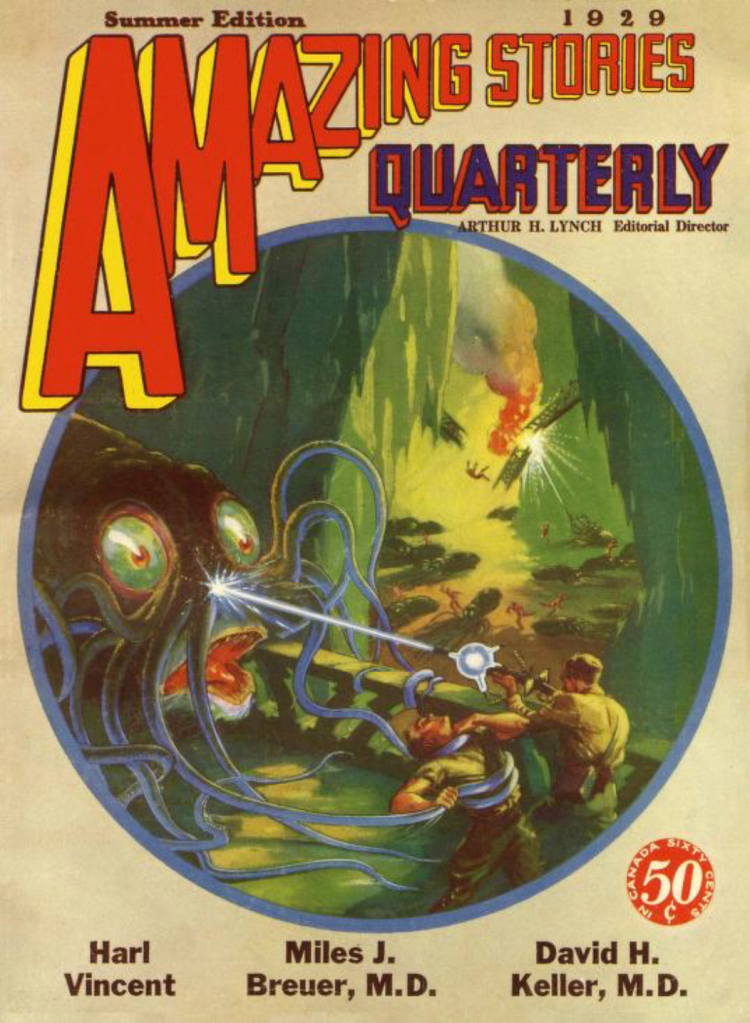

Leo Morey’s cover for Amazing Stories Quarterly, ed. Arthur H. Lynch (Summer 1929)

What technological achievements did Breuer’s science fiction foretell?

The only – but quite an important – Breuer’s achievement in this field is the idea of self-driving cars or autonomous vehicles. When you look into respective literature, you could usually find that the self-driving cars were first described in Breuer´s novel Paradise and Iron (1930), but – what I found – there was an early shorter version of this story published in Czech as “Vyšší tvor” in three instalments in Bratrský Věstník monthly in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Note that there was also an English version of the story published two years later as “The Superior Race” – even this edition was not known until recently.

The history of the concept of self-driving cars is thus six years older, and I am happy that one of the best car museums in the world – Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles – incorporated this information into their permanent exhibition which is describing the history of autonomous vehicles and the story of the first real one – Waymo – which is now being used as a taxi in Los Angeles and three other US cities. Breuer did not foretell many technological achievements, on the contrary, he was using his scientific knowledge and incorporated it into his stories. Being a medical doctor, he was extrapolating various ideas that could change future medicine, but he was also interested in physics, too, and his 1930 story “The Fitzgerald Contraction” is – according to Bob Silverberg – most probably the first science fiction based on the concept of time dilation.

Despite his prodigious technological imagination, you describe Breuer as having “little faith in technological progress” (43). What was his take on technology? Did it evolve over the course of his writing career?

That is true, but it was only in the later years of his literary career. What we know Breuer, his brother, and his father, were keen users of modern technologies. They had an advanced laboratory, where they even produced their own vaccines, their medical practice had an X-ray machine only a few years after it was invented, and they never hid their interest in using the most advanced medical methods and machines.

When Breuer started writing science fiction, he was amazed by the possibilities of new technologies, but as he had a life-long interest also in social studies, later in his career he became more skeptical. In the mid-1930s he repeatedly mentioned that technological advancement must go hand in hand with the social development of the society. Thus he disliked the late 1930s science fiction of so-called super science, and this was—as he once wrote—a reason why he stopped writing for genre magazines. His disillusion with science fiction is clearly seen in his virtually unknown late 1937 essay “Comparisons in Science Fiction,” where he states that the genre magazines publish only “adolescent material under the misnomer of science fiction.” This forgotten essay is also reprinted in my book.

Do any of Breuer’s stories touch on issues of the Great Depression?

Not much, maybe the 1931 novelette “The Legion of the Fittest” published in the non-literary magazine Social Science and never reissued since. Although the Great Depression is not mentioned, the story describing diminishing society sources, the majority of which are being used to cater to the insane, ill, and uneducated people, might be the reaction to the economic crisis. It would be interesting to delve into Breuer’s other writing which was published in Social Science quarterly published in Kansas. I am sure we could find a lot of interesting information on his worldviews. I have not yet had the chance to study it thoroughly.

Breuer, like other SF authors and fans, took part in debates over the genre. What positions did he take?

Breuer was one of those writers who took Gernsback’s appeal for constructive criticism seriously. He became an avid contributor to a section titled “Discussions” where many writers and readers contributed their views. Not only did he criticize other writers for their shortcomings—usually in scientific knowledge—but he soon became an advocate of a new literary genre. He was shaping the discussion on science fiction, but he also thought about its future development. He believed in science fiction, he even once wrote that it is a critical component of the development of human civilization! He supported that the stories have strong and trustable scientific elements, but he also asked the authors to conform to modern literary standards.

This was around 1930, and even then Breuer urged not to write some “sort of a raving fancy, a wild, incoherent hodge-podge of machinery.” But exactly this happened in the late 1930s, which caused Breuer to stop writing for genre magazines. He lost interest, as he wrote in 1937.

Leo Morey’s cover for Amazing Stories Quarterly, ed. T. O’Conor Sloane, Ph.D. (Winter 1931)

What was Breuer’s relationship with Jack Williamson?

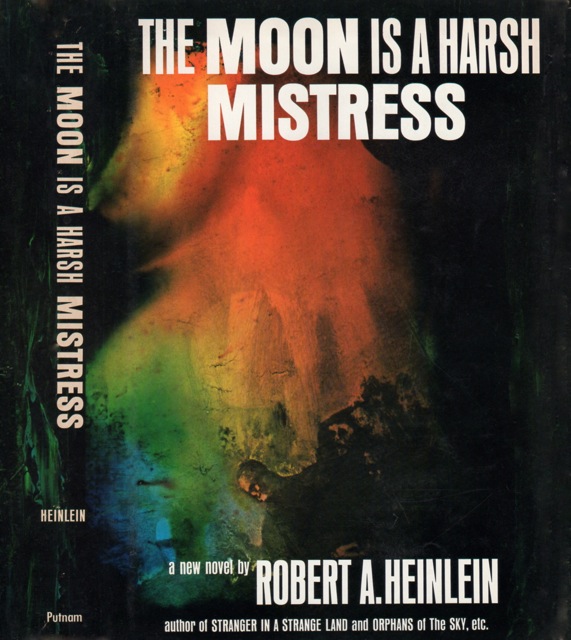

For a short period of time he was a sort of literary father figure for the very young Williamson. He was a mentor, but after writing one story and one novel, Williamson learned everything he wanted and cooperation ceased. In any case, there is one collaborative work of real importance in the history of science fiction—the novel The Birth of a New Republic. Narrated by an old man seventy years after the Moon’s independence, it is full of exciting action, adventures, and ideas. Not so much interesting today, except for the fact, that it directly influenced Robert A. Heinlein to write his acclaimed novel The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (1966).

Your book charts Breuer’s waning enthusiasm for the new literary genre, which eventually turned to “outright skepticism” (78). What caused it? How would you characterize his final publications in the mid-30s?

As I mentioned, it was the superiority of science over literary qualities in late 1930s SF he disliked. Breuer really felt that science fiction deviated from its original path, and he thus stopped publishing in genre magazines—at least he declared it this way. I feel that this was not true—in the mid-1930s Breuer went through an incredible number of problems—both personal and artistically. Breuer was then repeatedly admitted to hospital with various illnesses, also his marriage was in ruins which ended in a divorce at the end of the decade, and he was terribly overworked as both his father and his brother left their joint medical practice in Lincoln, Nebraska, and he had to do everything alone. Additionally—not only did he have no time to write, but a few stories, which were published in the late 1930s and early 1940s were by far of lesser quality.

Irv Docktor’s cover for the 1st edition

What was Breuer’s literary legacy and importance?

Breuer’s untimely death in his mid-fifties in 1945 practically stopped any interest in his writing. I am sure, if he was alive for—say—ten more years, he would become widely anthologized, he would take part in discussions on new science fiction emerging… There was an attempt by Jack Williamson to publish Breuer’s Paradise and Iron and a couple of stories shortly after his death, but this never materialized and Breuer fell into obscurity.

There are at least two stories by Breuer where I can clearly see the importance of the future development of the genre. The first one is overt—Robert A. Heinlein confirmed that Breuer-Williamson’s The Birth of a New Republic was an inspiration for him to write The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. There is another case—Breuer’s “The Perfect Planet” (1932) (read online) with its idea of a gas that changes intelligence is in some way similar to the famous Flowers for Algernon (short story 1959, novelized 1966) by Daniel Keyes. Did he read Breuer’s story, or is it only an accidental similarity? We will most probably never know.

What struck me the most while reading your book is a fascinating issue of historical methodology: the role of more ephemeral types of publications in the origin of the SF genre. You highlight a vast range of places that published SF: university literary magazines (The University of Texas Magazine), local publications of the Czech-American community (Bratrský Věstník, Amerikán Národní Kalendář), medical journals SF (The American Journal of Clinical Medicine), etc. that are not traditionally included in histories of the genre. Should they be considered in SF histories?

I would answer yes and no. I think it very much depends on the author of these scattered stories. If the author later on entered the science fiction realm, and became relevant in the science fiction universe, among science fiction fans and readers, in that case it is important to study this author’s beginnings, to learn more about changes in his literary style, development of his ideas and his viewpoints. This is undoubtedly the case of Breuer.

But very often genre stories published in such marginal magazines had no influence on other writers, no followers, no genre readers. These were often written by otherwise unknown writers, often being their only science fiction story… In that case, they are the “missing links” in the genre’s history. Any such story, regardless of its quality, which had no follow-up, is irrelevant to the history of the genre.

I will mention an example from the history of Czech science fiction. As SF was not supported by the Communist regime, and there was no science fiction magazine or even publishing house publishing it in specialized series until the 1990s, everybody who loved SF had to read his favorite genre in many different books and magazines. We had a very good idea, that good SF stories were published in really atypical periodicals. But nobody read everything, of course.

1961 Czech edition of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1950)

There was practically zero Anglo-American science fiction published in the Czech language in the 1950s and 1960s, with one exception—Ray Bradbury—whose books were published by the best Czech state publishing houses in high print runs since the late 1950s. Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles had a really serious impact on original Czech science fiction. Some of Bradbury´s stories appeared in various periodicals, and SF fans and readers were creating their own scrapbooks, mimeographed them, exchanging these stories, etc. Then we thought we had a perfect idea of what was published, and we read literally everything published in Czech which at least resembled SF.

But—until last year no Czech SF fan had even the slightest idea that in the 1950s, the times of the worst Communist terror, when everything American was banned, and science fiction was not published at all, translation of Edmond Hamilton’s space opera emerged in installments in communist army magazine. If read by future SF writers it could have a real impact…maybe we could have an original “communist” space opera… but it had no impact, as visibly nobody had even read it. Such publication is thus part of the history, but only as a lost chance. An interesting footnote…

I thoroughly enjoyed your book and interview. Thank you so much!

You can snag a copy of his book here.

Notes

- Relevant previous posts: Interview with Jordan S. Carroll, author of Speculative Whiteness: Science Fiction and the Alt-Right (2024); Interview with Adam Rowe, author of Worlds Beyond Time: Sci-Fi Art of the 70s (2023); Al Thomas’ “Sex in Space: A Brief Survey of Gay Themes in Science Fiction” (1976); and Sonja Fritzsche’s “Publishing Ursula K. Le Guin in East Germany” (2006). ↩︎

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 6/24/25 You Gets No Cred(ential) With One Spaceball | File 770

Fascinating stuff, never heard of Breuer before. Seems like something Rachel Cordasco/SF in Translation would be up on. The cover for that Man With the Strange Head collection is great, will pick that up if I ever come across it.

Glad you enjoyed it! Re-Rachel S. Cordasco — > I definitely sent the interview her way as it brings up a lot of interesting issues about translation.

I also need to read more of his work! I’ve read “The Birth of a New Republic” (1931) with Williamson, and a few late period Breuer stories that touch on the Great Depression like “Mechanocracy” (1932) and “The Company of the Weather” (1937).

Joachim, my thanks for a great interview on Miles J. Breuer. I believe I had heard somewhere that he was of Czech origin, but I knew nothing more. Checking, I rather think the only fiction by him I have ever read is “The Gostak and the Doshes” in Leigh Grossman’s anthology “Sense of Wonder”. I appreciate the suggestions for reading more of his fiction.

Thanks for stopping by. Glad you enjoyed it. If you get to one of his stories, let me know.

Pingback: Jaroslav Olša, Jr. at SF Ruminations – Speculative Fiction in Translation