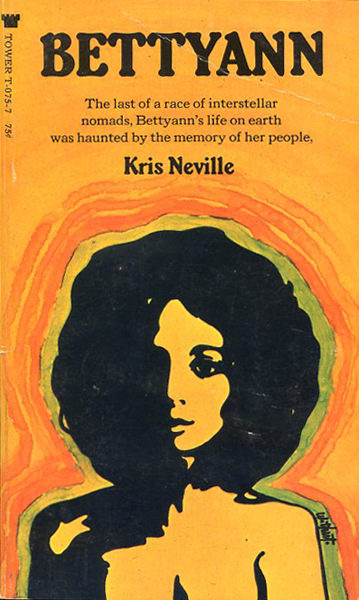

(W. Thut’s cover for the 1970 edition)

4/5 (Good)

So the Amio were deficient, from the very beginning, and were born weaklings, untested, and had gone their own solitary way. […] [Bettyann] would reinfuse in them the vitality that their own development had ultimately denied them and contravene the defeat that was foreshadowed in the limited dreams and ambitions of their father’s father’s father’s father’s father, backward to the time when myth told little that one might truly believe, except that the Amio were always, from the beginning, one” (78).

Since the beginning of the year MPorcius, who presides over MPorcius’ Fiction Log, has reviewed a handful of Kris Neville’s short stories (here and here). Because the name was on my mind and I had not read any of his work in the past, I eagerly picked up a copy of his fix-up novel Bettyann (1970)— which contains contains two previously published stories “Bettyann” (1951), which appeared in New Tales of Space and Time, and “Ouverture” (1954) which appeared in 9 Tales of Space and Time, both edited by Raymond J. Healey. The novel is hard to find as it was only published by Tower Books.

Neville is praised by Barry N. Malzberg as an author, if he had not abandoned the field for the sciences, who could have been among the “ten most honored science fiction writers of his generation” (Malzburg’s intro to Neville’s “Ballenger’s People” in the 1979 Doubleday collection Neglected Visions).

Bettyann demonstrates some of this promise.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis

The premise of Bettyann is pure pulp but swaddled up in the distinctly non-pulp aura of elegiac melancholy. The first plot threat follows the Amio who live on “their great Light Ship, which sailed along the currents of the universe outside the Einsteinium continuum” (9). They all join together in a vast subconscious mind, “shaped by racial memories,” where every death results in the each being diminished as a part of the whole goes missing (9). The Amio are nomadic, their ship is their home, their bodies are naturally immaterial but able to become solid and take on whatever form they want when they attempt to change cultures their encounter.

The Amio journey from planet to planet attempting to impart some of their ageless wisdom. Once they journey down to a planet where crab people life but encounter rituals counter to their conception of the world. The leader of the crabmen proclaims, “And warriors, attend: Select those to be torn apart in honor of our guests” (22). The Amio feel the pain of their own while the crabmen tear each other apart “to become gods, and this is the only path one may take to obtain that goal” (22). They hold on to the idea that although ideas they disseminate might not immediately transform a people in the future some kernel of what was planted might emerge.

As more and more die as a result of their inability to transform those they encounter, the Amio realize that they are trapped by their past.

“[Lewan’s] own thoughts reached back to childhood and beyond that, in a queer, yet valid way, to the childhood of his parents and their parents and their parents and their parents and their parents and their parents and their parents…. Spreading outward in the end to embrace everybody. For each of those distant, forgotten people had molded him and stamped themselves upon him and shaped him. He could never break out of that form he was cast in and think unthinkable thoughts” (29).

One has the feeling that the Amio have tried for generations to influence the people they encounter with the same predictable patterns of defeat. They are bounded by their birth and its is up to someone separated from them at birth to influence (perhaps) the cycle. They collectively decided that the races was dying not a literal death, but a “psychic, spiritual death, a death of the will” (71). And only a child could restore them, “only a child could save them” (71).

The second plot thread follows Bettyann, an Amio child trapped inside of a baby’s body: “‘She’s actually growing in this body, have you noticed? She’s heavier. Her arms are getting fat.’ ‘We may have trouble getting her out’ (7). Bettyann—“she was the youngest of us all, and none have come after her” (10)—is stranded on Earth after the two aliens posing as her human parents are killed (apparently they can be killed if they are caught unawares) in a car wreck. Her arm is damaged beyond repair.

She is adopted by Jane and Dave who are also trapped by a certain sense of the past, of the world changing before their eyes in directions they cannot grasp. Dave sinks into nostalgic daydreams where he imagines what memories “they would lay out for Bettyann to think back to with sadness when she moved away from them into the world of her own choose” (19). Both are struck by existential angst as the indistinct forces of war rages around them. Jane’s thoughts are the more disturbing as she lays in bed: “It seemed to her, sometimes, that the God of the real universe must have died a tiny baby in some other universe, and all the galaxies in the sky were but exclamation points to punctuate its nameless terror” (39).

As Bettyann grows her alien nature is molded to fit her new form: “slowly there were regroupings to dictate of the form she wore, and new pathways came into being in response to the logic of flesh” (11). As she ages she has numerous experiences that feel distinctly inhuman, “lying in bed one night, she awakened to feel her thoughts twisting in her body like an imprisoned thing seeking freedom” (32). Later in life she feels that she might be “an attraction in a carnival side show” (11). Of course, it is only near the end of the novel that she realizes who she is.

Bettyann is a remarkable and precocious young girl obsessed with learning about her world, her past. Neville is adept at the small touches that make her childhood tangible. For example, Bettyann’s doll, “all day he would read. At night she would take him to bed with her and he would whisper stories to her” (24). She loves to read (74) political philosophy, history, and literature. Her father desperately wants her to make something with her life, pursue the sciences. “Science […] is the thing for girls nowadays” (80). Perhaps because he feels that his life has not changed the world in any meaningful way.

Both storylines culminate as the Amio realize that they need to find the girl they abandoned (accidentally) on Earth and Bettyann realizes the nature of her past.

Final Thoughts

As with many fix-up novels that are not simply thematically linked novels, there are some structural issues with Bettyann. The parallel nature of the two major story lines—the ideological/socialogical crisis of the Amio that results in their search for Bettyann and Bettyann’s growth into adulthood—ends two-thirds of the way through as the Amio exit the narrative until the last few pages. Likewise, some portions have a distinctly 1950s feel while other portions feel like their were written in the late 60s. Previously published material stitched, expanded, and modified does not often yield seamless constructions.

Structural issues aside, Bettyann‘s thematic focus on collective memory, nostalgia, historical cycles, the influence of the distant past on current thought, of youth and old age, societal senility and decadence is all a breath of fresh air. The pulp premise of alien stranded on Earth is recast in meaning-rich ways. The way of telling oozes elegiac mournfulness, a testament to Neville’s often powerful, but careful, prose.

Why this was never reprinted in the US is beyond me. Recommended.

For more book reviews consult the INDEX

Great review as always J, the cover reminds me of an old Stax Records heavy funk and soul compilation LP I have lurking somewhere in the far reaches of my music library!

Thanks, Have you read anything by Neville? I get the impression that Tower Books didn’t have a huge art budget. A lot of their covers are rather pedestrian…

Such as the island of New Guinea as a “dragon.”

Sadly I haven’t as yet discovered Neville, perhaps now is the time. The art on this (and the other title you mention) is pretty lamentable and largely throwaway isn’t it?

This one seems rather hard to find…. But, was surprisingly ruminative and well written (as hopefully my review indicated). His short fiction might be easier to find (check the reviews I linked to MPorcius’s Reading Log that I linked in the intro).

I just finished the Bettyann short in the Greenberg/Olander edited Science Fiction of the 50s. It’s left me wanting to read more Neville. And there is a brief afterword in the collection by Malzberg you maybe interested in.

Yeah, Malzberg was a major fan of his. Which is the reason I tracked down the hard to find Tower books edition of Bettyann. If you liked that story you should find a copy of the fix-up novel!

Yep looking for a copy of it at the mo. Then all that is left to do is finally read Beyond Apollo 😉

That is where I read the original short story of this too. Would you really like to see if the full length novel fix-up or not is just as good.

I got a copy of the novel and it appears that Neville in effect inserted the story of the Amio’s journey into the first short story. I still haven’t read the novel, but have read both of the original shorts. And I managed to get hold of Neville’s coda to these works, ‘Bettyann’s Children’ to be found in the collection Demon Child (1973). It is definitely worth checking out.

More importantly (haha) have you finally read Beyond Apollo (referencing your earlier comment)?

Let me know what you think of the section added in the novel. You should review it!

I did not realize that there was a coda… hmm.

Pingback: “Run, the Spearmaker” – Lil Neville and Kris Neville | works & days

Pingback: Bettyann, by Kris Neville | gaping blackbird

I read this recently and mostly agree with your review – maybe instead of sadness, I saw disappointment as the primary mood. This is a hidden gem of science fiction, if not a lost classic.

Thanks! I read your review as well. Sadness and disappointment are such related emotions that perhaps we can say both are present and both were intended.