Mitchell Hooks’ cover for the 1st edition

3.5/5 (collated rating: Good)

Over the years, I’ve slowly made my way through a substantial portion of William Tenn’s output: I’ve reviewed his only SF novel Of Men and Monsters (1968), two short story collections–The Human Angle (1956) and Of All Possible Worlds (1955), and three additional short stories “Bernie the Faust” (1963), “Eastward Ho!” (1958), and “Generation of Noah” (1951). I’ve found him an effective satirist with a penchant for often self-defeating twist endings. At his best, Tenn challenges grand narratives of American progress and exceptionalism, 50s consumerist culture and gender roles, and renders an absurdist spin on Cold War conflict. I imagine his reluctance to write novels relegates his often brilliant ouvre to the fringes of contemporary interest in 50s SF.

Time in Advance (1958) contains four solid but unspectacular visions. I recommend the collection only for fans of his work. If you are new to Tenn’s brand of intelligent satire, check out “Down Among the Dead Men” (1954), “Eastward Ho!” (1958), “The Liberation of Earth” (1953), and “The Servant Problem” (1955) first.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis

H. R. Van Dongen’s interior art for William Tenn’s “Firewater” in Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (February 1952)

“Firewater” (1952), 4/5 (Good): First appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, ed. John W. Campbell, Jr. (February 1952). You can read it online here.

Easily the best story in the collection, “Firewater” puts an original and fascinating spin on the first contact tale that’s simultaneously in dialogue with the American past. In the years after first contact, blinking light-like aliens are allotted “reservations” in the world’s deserts. In possession of far superior technology, a few brave humans attempt to interact with the alien presences, whom they assume feel far superior to the humans around them. Most humans who interact with the aliens go insane yet receive, in return for a transaction that isn’t entirely clear, unusual powers. A few business men choose to bring in the insane emissaries of the aliens and conduct exchanges for alien technology. Algernon Hebster, motivated entirely by profit, runs a not entirely legal business, Hebster Securities, gleaning details from the linguistic chaos of the transformed humans. He uses the fragments he uncovers to create new fashions and gadgets for the American suburban life.

One day he’s approached by the UM Special Investigating Commission with a deal. Hebster’s unique skills are needed to confront a growing far-right movement called Humanity First that seeks to destroy Hebster and evict the aliens from earth. If he doesn’t help, his own business will be investigated and potentially destroyed. Both sides spy on each other. Hebster finds himself in a meeting with the leader of Humanity First, who expounds his own fascist delusions. He must take actions into his own hands. Can conflict be avoided? Are the aliens as superior as they assume? Or are both sides possessed by a psychological block unique to their species? As with the superior “Eastward Ho!” (1958), Tenn places his future world in dialogue with American narratives of the past–in particular Native American history. I’d love to explore these historiographic and narratological parallels in more detail in a longer-form article.

Recommended for fans of unique first contact stories.

Dick Francis’ interior art for William Tenn’s Galaxy Science Fiction, ed. H. L. Gold (August 1956)

“Time in Advance” (1956), 3.5/5 (Good): First appeared in Galaxy Science Fiction, ed. H. L. Gold (August 1956). You can read it online here.

Imagine a future in which colonization on alien worlds creates a desperate need for almost sacrificial labor. No one wants to volunteer. However, planets must be conquered and massive bugs and monsters rooted out and slaughtered before humanity can lay down outposts in the far beyond. Somehow companies in charge of colonizations manage to push a law that would allow men to serve hard labor for crime. In addition, if you’re itching to murder someone you can sign up for punishment before you commit the crime. To incentive volunteers, you’ll receive half the sentence. If you murder someone and then are convicted, you’ll serve a full sentence. If you survive, you’ll be able to return to Earth already having served a shortened sentence for a crime you have yet to commit.

Two men return from their service making the stars fit for humanity’s inevitable expansion. Both survived, traumatized, and both served long enough to murder anyone they might wish. Both signed up because they wished to commit violence. The media descends in droves desperate for the ultimate scoop: who are YOU going to murder? The story follows Nicholas Crandall. He originally signed up for his punishment in advance as he wanted to murder his business partner who stole his invention. However, when he returns a whole series of people reach out confessing their sins and breaches of trust thinking they might be the target of his murderous ire. Will he murder his original target? Or someone else?

“Time in Advance” contains an outrageous and non-sensical premise for sure. Tenn posits a gentle satire of humanity’s quest for the stars. The story shifts with the focus on Crandall’s life, one spent in a similar quest for financial gain. He was oblivious to the actions of those around him. Had he lived a life worth living? Was he blind to what gave value and worth in the present? Both men find themselves mired in an entirely different existential state as their narratives of purpose come tumbling down.

Somewhat recommended.

Robert Engle’s interior art for William Tenn’s “The Sickness” in Infinity Science Fiction, ed. Larry T. Shaw (November 1955)

“The Sickness” (1955), 3.5/5 (Good): First appeared in Infinity Science Fiction, ed. Larry T. Shaw (November 1955) You can read it online here.

The era: the paranoid depths of the Cold War. Physical conflict seems inevitable: “Something had to be done, and done fast” (83). The last-gasp cooperative idea to generate detente? A multi-ethnic expedition, lead by the non-aligned India, sets off to explore the desert reaches of Mars. Both the Americans and Soviets implant a secret service member into the astronaut ranks with plans to take over if needed. In order to facilitate cooperation in the face of the omnipresent paranoia of secret ploys and plots, the astronauts must learn the language of the other superpower. American astronauts must speak Russian to each other, even in private. Soviets must converse in English. As the expeditions approaches its conclusion, the Russian Belov discovers well-preserved ruins on Mars. A sinister sickness begins to infiltrate the expedition’s best attempts at quarantine and control.

I read this initially for my series on subversive takes on space travel. It’s paranoid. It’s a fascinating manifestation of contemporary fears. Unfortunately, Tenn is wedded to “twist” ending that weakens and diminishes all the effective setup work. Rather than an expedition that falls victim to the paranoid whirlwinds on Earth’s surface or realizes the value of an alternative, Tenn settles on a third far less interesting reveal. I find Tenn’s obsessive hunt for endings with sufficient twist, especially the tacked on sort, diminishes narratological impetus and thematic cohesion.

I’m not entirely sure what to make of this one. The rating comes from the setup and intriguing suggestion that the un-aligned Third World might be valuable players in a more peaceful future. I found the other elements disappointing.

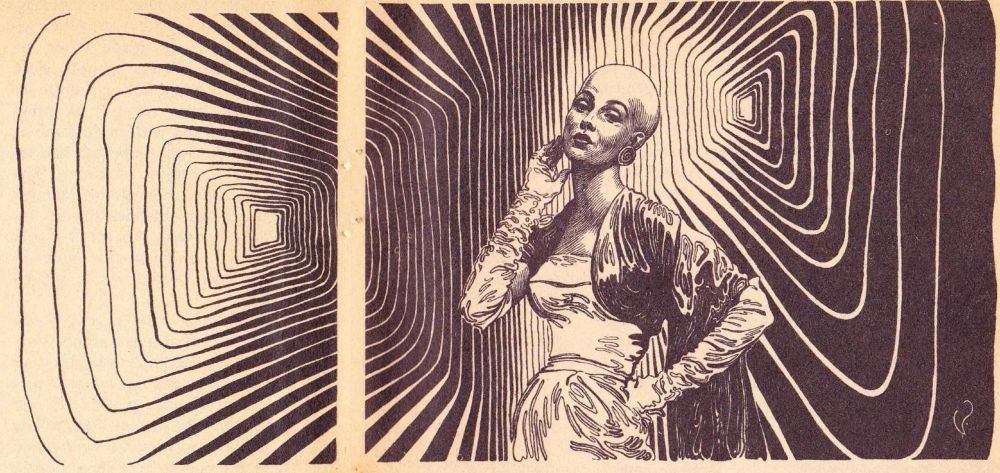

Virgil Finlay’s interior art for William Tenn’s “Time Waits for Winthrop” in Galaxy Science Fiction (August 1957)

“Winthrop Was Stubborn” (1957), 3/5 (Average): First appeared in Galaxy Science Fiction, ed. H. L. Gold (August 1957). You can read it online here.

A group of common Americans, a cross-section of society, is selected for an experimental voyage into the future. There’s a problem. Winthrop, the oldest of the bunch, wants to stay in the 25th century. The others find the constantly shifting hallways and furniture, unusual rituals, discombobulating personal transportation, food consumption as symphonic appreciation, fantastical technology, and unusual future denizens too different and shocking. Winthrop, a product of the Great Depression, reminds his fellow travelers of his “lousy job and lousy life” (106). He was the kid left by his parents in the breadlines as they hunted for work. And when the Depression ended, he could only find menial jobs that never granted security or a moment of peace. Winthrop enjoys the post-scarcity 25th century. He enjoys relaxation. He’s finally able travel and participate in new experiences of every imaginable nature with his daily cares lavishly provided for. His fellow travelers beg him to return. They all need to jointly return at the assigned time else they won’t be able to return at all.

As with “The Sickness,” I found this story’s “twist” ending deeply unsatisfying. It entirely dodges and diminishes the conundrum, the generational issues and desires brought up by Winthrop’s need to stay in the future, Tenn lays out. Is there no way past generational divides? Can we really never bridge differences? Spectacular art by Finlay aside, this is not Tenn at his best.

Not recommended.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

‘Time In Advance’ was adapted in the 60s for the BBC’s ‘Out Of The Unknown’ series. Not entirely successful as drama but explores the premise effectively.

Thanks for stopping by,

I can’t say I’ve ever looked through those anthology TV series in any detail. I think your take on the episode matches my take on the story — “Not entirely successful as drama but explores the premise effectively.” Have you read any of his fictions? If so, do you have a favorite?

I’d argue much of Winthrop captures the quintessential Tenn.

Because certain stories parody or extrapolate specific social issues it’s easier to identify that as the point of the satire. But there is an underling ethos that motivates that satire, and derives from an issue fundamental to sf. Tenn’s fictions depict humans who are always parochial and inferior to the situation they encounter. Be it a future society or the arrival of aliens his characters generically lack the resources to rise to the occasion, to understand or appreciate. They are steam-rollered, impotent or driven to pained frustration. The lesson Tenn takes from Well’s War of the Worlds – If there had been no banana skin of bacteria then mankind and Earth would have fallen. This attitude is why he eventually became unpublishable in Campbell’s Astounding. Given sudden access to superior technology we are no more than children playing catch with grenades. Our limitations become inescapable when given opportunities of ascendance and transcendence. This, in various forms, is the scenario that he repeats. Confronted by the “future” (that is the very point of sf) in some form or other we can’t happily engage with it, because we are cognitively and conceptually hobbled. We’re just not up to it and it’s just not fair. “We’re going to remain as stupid as we’ve been”

In the same collection, a similar thematic core — “We’re going to remain as stupid as we’ve been” — can be used to describe the superior “The Sickness.” Only far greater intelligence can get us out of the Cold War mire. A similar core can also be applied to his far far far better story “Easterward Ho!” or “The Liberation of Earth” both of which I enjoyed more than Winthrop. All of this is to say, I understand your point but found myself put off by the cop-out ending. I think he explores humanity’s inability to escape previously delineated rituals and patterns of decay and collapse in a more adept way in the stories I listed earlier.

The expectation that many sf/fantasy/horror stories should end with a twist does mean that the standard blackly comic surprise is some variation on “Suddenly, everyone was run over by a truck. -the end-“ from Michael O’Donoghue’s How To Write Good. A fair number of Tenn’s stories follow this, but it requires a degree of finesse which Tenn doesn’t always manage.