3.5/5 (collated rating: Good)

Ever since I read Judith Merril’s “Daughters of Earth” (1952), I’ve been fascinated by her subversive takes 1950s-60s gender roles and classic SF tropes. Survival Ship and Other Stories (1974) contains twelve short stories and a never-before-published poem selected by the author.

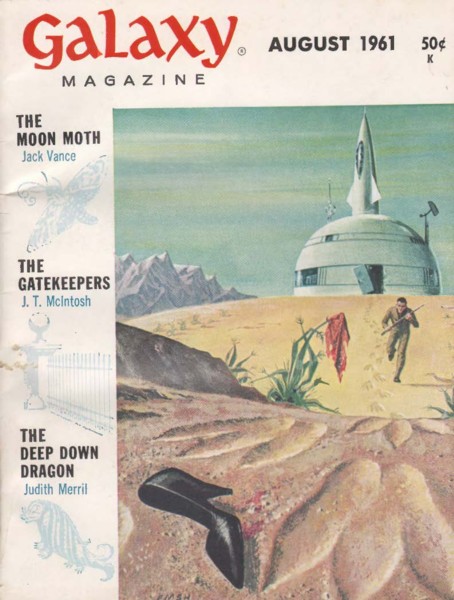

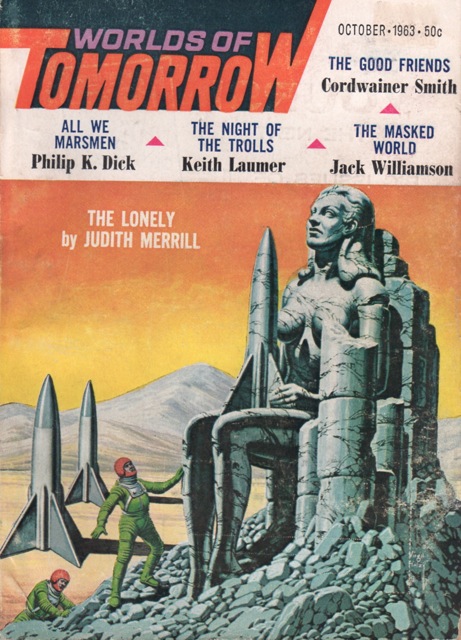

In addition to the merits of the tales within, I found Merril’s brief reflections on her early work fascinating. For example, she ruminates on the failure of her planned novel based on the generation ship launched by The Matriarchy in “Survival Ship” (1951), “Wish Upon a Star” (1958), and “The Lonely” (1963). She also describes a magazine “cover story” commission. The author would be provided with the cover art and asked to write a story containing its elements! The following three in this collection—“The Shrine of Temptation” (1962), “The Deep Down Dragon” (1961), and “The Lonely” (1963)–were “cover stories.”

If you enjoy her fiction, it’s probably best to pick up her omnibus Homecalling and Other Stories: The Complete Solo Short SF of Judith Merril (2005) unless you’re like me and prefer the old editions!

Note: Only seven of the stories and the poem in this connection are new reads. I reviewed the other five previously and collated the reviews (with minor edits and links to the originals).

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis (*spoilers*)

“Survival Ship” (1951), 3.5/5 (Good): The Survival, “the greatest spaceship ever engineered,” blasts off on a fifteen-year journey to Sirius (9). But there’s a secret! The millions of well-wishers do not know the real identities of the twenty four crew. The world followed the details of the mission preparation: from detailed requirements and proficiencies to the rigorous training. Each crew received a nickname and the public obsessed over their “small characteristics and personal idiosyncrasies” (9).

After launch, the twenty women awake and go about their duties. They inspect the hydroponics bays, the engines, the control mechanisms. In this future, women are deemed more suitable for command positions. Captain Melnick reminds the women, “we are hardier, longer-lived, less susceptible to pain and illness, better able to withstand, mentally, the difficulties of life of monotony” (15). The four men would be the fathers of the next generation and parenting would be shared in non-traditional family groups (15).

Merril deliberately withholds pronouns until the last few pages. While I’m often not a fan of structural “gimmicks” of this nature, I can imagine the impact of Merril’s radical formulation of the future of space exploration. “Survival Ship” pairs nicely with the superior “Daughters of Earth” (1952). Both place the agency of the pulp conquest firmly with female actors.

Unfortunately, despite two later short stories in the same sequence—“Wish Upon a Star” (1958) and “The Lonely” (1963)—Merril’s plans for a novel on the Survival never materialized.

“Wish Upon a Star” (1958), 4.25/5 (Very Good): Previously reviewed for my series on generation ship short stories here.

In Merril’s “Daughters of Earth” (1952), she refashions the classic pulp SF tale of male exploration of the galaxy by tracing, in biblical fashion, one family of female explorers. In “Wish Upon A Star” (1958), Merril reworks another trope—the male hero on a generation ship who discovers the true nature of his world by fighting against the repressive forces that keep stability and order.

On Merril’s generation ship the gender roles are reversed. Men care for children and perform other domestic acts while women are promoted up the chain of command. By focusing on a young boy attempting to understand the world around him, Merril subverts the reader’s expectations of the male hero. His everyday struggles—his desire to learn the details of the voyage and have access to the same education as his female counterparts—mirror those of women in 50s society.

Sheik, a thirteen year-old child of the second generation of crewmen, spends his days caring for plants in Survival’s hydroponics bay and looking after the younger children. The plants, and their shadows, thriving under their grow lights are his passion (89). He yearns to learn what the women on the ship are allowed to know: “They’d make [Naomi] read all the books he wanted, whether she cared or not, and put her to learn in the lab” (88). Women on the Survival are destined for command. Men care for the children and perform lower-level maintenance.

The Survival, designed for up to four generations of colonists, left Earth to find a habitable planet for “the spillover of the home world’s crowded billions” (94). The original crew of twenty-four included five women for each man for “obvious biological race-survival reasons” (94). The women prevent the men from learning the status of the voyage.

Chaffing against the constraints imposed on him, Sheik’s father Bob remembers society pre-departure, which he would describes as a Golden Age, where men “ruled their homes” (94). In paranoid fashion Bob speculates with his male friends that the women “wouldn’t want to land” (96) in order to keep their positions of power intact. Sheik doesn’t know precisely what to make of these paranoid declarations, “fairy-tale stuff” (94), as he is a product Survival’s new society. But the relentless desire for knowledge and the ability to make choices and facilitate change course through him. He is left to wish for change. But can society change?

In order to identify Merril’s reworking of the generation ship trope, it is worth comparing her depiction of women to that of Chad Oliver and Clifford D. Simak. In Oliver’s “The Wind Blows Free” (1957) women are entirely secondary to the narrative. It is unclear if any women have escaped the vessel. In Simak’s “Spacebred Generations” (1953), Jon refuses to tell his wife May his important role in bringing about the end of the voyage. Only at the end does she learn of Jon’s mission and she attempts to help him. Her interpretation of their new freedom boils down to the question: “Can we have children now?” (21).

I would suggest that Merril’s story allows her to explore the experiences and thoughts of women relegated to the periphery. At no point does the perspective shift from that of her young narrator. We see only what he is allowed to see. His thoughts are his own, but what he is allowed to say is constrained. Sheik is not the center of action. He has limited knowledge due to his gender and age. He observes the world around him. The adult men dream and even plot the revolution that might happen when, and if, a suitable planet is found. Sheik on the other hand is a product of the second generation. He struggles with his proscribed role in society but must soldier on in the only way he knows.

Merril presents a slice-of-life tale rather than an action-packed fulcral sequence in the history of the voyage. For all we know the end of the voyage is neigh but that knowledge cannot be disseminated to the men. And it’s in this tentative gray area of the periphery, in the shadows of plants, that Sheik inhabits and dreams.

A radical story but a quiet one—a slice-of-life rumination where the action stays in the distance, in the board rooms and classrooms of the female crew, the places where men cannot go.

“Exile from Space” (1956), 3.5/5 (Good): A disconcerting tale that highlights the strange rituals of human existence by following the life of a young woman who seems alien: “I was born in this place, but it was not my home” (34). She fumbles through normal activities, like going to the drugstore and renting a hotel room, her behavior patterned on what she saw on television. The world presented by media does not prepare her for what she will experience. And of course, there’s a boy named Larry. Larry, perplexed by her behavior, asks: “What are you? What makes a girl like you exist at all? How come they let you run around on your own like this?” (53).

A woman raised by aliens plopped into 50s America sounds like the perfect light-hearted romp. I found, despite the elegant simplicity of its telling, a disturbing undercurrent of dread: the young woman’s desperation at performing the right action, replaying the scenes on TV, of fitting in…

“Connection Completed” (1954), 2/5 (Bad): Previously reviewed here.

A man gazes at a woman through a window. What transpires are a series of thoughts projected by both characters attempting to compel the other act and thus demonstrate the veracity of their telepathic experience. Both are fearful that it is all a delusion. If Merril pursued a SF horror avenue rather than the rather tepid conclusion, the story might have been more intriguing.

“The Shrine of Temptation” (1962), 4.5/5 (Very Good) is the best story in the collection!

Academic anthropologists observe an island community on an alien planet. Lallalyall, aka Lucky, approaches the anthropologists and becomes their liaison to the community and its fascinating cyclical formulations. As Dr. Jennifer R. Boxwill, the linguist, slowly pieces together their language, a series of mysteries emerge–what is the role of the Shrinemen whom Lucky aspires to join? What is the true meaning of the constant refrain on the native lips, “hallall”?

“In the village and fields, we heard it incessantly. It was the only no-answer a child ever got. No question was forbidden for young ones to ask—but some were not answered in First Age, and some not in Second. Hallall, they were told, hallall, ye should know” (89).

Everything about the society and its functions seems to be planned. Ritualized. Internalized in native behavior. Knowledge doesn’t seem to be hidden from view. The cycles seem accepted. And then an otherworldly event unfolds….

I found the world immersive and the mystery compelling. Perhaps a Cold War allegory of how the American people rationalized “security” and “conformity” in an era of oppression?

“Peeping Tom” (1954), 3.5/5 (Good): Previously reviewed here.

Telepathy. A jungle. A nameless war. Tommy Bender, “a nice American boy,” recovers from an injury (22). In the jungle dampness he learns about the less than tender thoughts of his fellow wounded comrades who lust after their nurses. When Bender can walk again—remember he’s “a nice American boy”—he pays for sex, with a “disconcertingly young” woman (pimped by her young brother) in the nearby village, with cigarettes (28).

One day when he seeks to assuage his lusts, he enters the hut of the local sage and begins to uncover his telepathic abilities. His nurse love interest is also one of the sage’s students…. “Peeing Tom” rises above many similar telepathy stories not due to the very predictable twist ending, but the strange commentary on the transformative effects of injury and war. This was written after the Korean War. Tommy Bender’s is not really “a nice American boy” and is solely motivated by his own lusts and passions.

“The Lady Was a Tramp” (1957), 3/5 (Average): Previously reviewed here.

This is without doubt the most unusual story in the collection. The premise: IBMen plot the trajectories and jumps of spaceships, an especially dangerous job on a merchant ship due to the small crew compliment. The female psychological officer, who holds the rank of Commander, likewise has an important role to play in the microcosm of the ship. A role that the new IBMan Terrance Carnahan does not want to believe exists. Merril purposefully conflates the spaceship, the Lady Jane, and Anita, the psychological officer. Terrance considers both “tramps.”

The pros: The story is psychologically tense. Also, the focus on some elements of life in a spaceship exudes a certain realism. The cons: Merril clearly positions Anita as the power on the spaceship, the woman who holds everything together by having sex with all the male crew members. She uses her sexuality to keep the crew from fracturing. Just as Terrance must conquer space to achieve his dream, he must also put aside his reservations and take advantage of Anita’s role. Really?! I find it rather unsettling in its ramifications especially since Carnahan never puts aside his extreme sexism. Very problematic.

“Auction Pit” (1946), unrated: As this is a poem, I decided not to review it. A series of women exhibit themselves (in a brothel?) before men. I assume there’s a shapeshifter as well? If SF(ish) poems are your wheelhouse, this might be worth tracking down. It’s not for me.

“So Proudly We Hail” (1953), 3/5 (Average): Deploying quotations from the Star Spangled Banner as an organizing principle, “So Proudly We Hail” relates the marital pressures an astronaut couple experience in the lead-up to launch. Merril positions women as equally (and in some cases more) important than men in the conquest of space. Unable to effectively communicate their secrets and fears due to all they had wrapped up in the mission, the story lurches to an abrupt fiery end.

I’m not convinced by the ending or the verses from our national anthem. Merril herself seems dissatisfied in the comments: “it seems to me that” the story “has merged to one ironic statement” (166).

“The Deep Down Dragon” (1961), 3.25/5 (Vaguely Good): A wall projects an imagined scenario of a test subject. The test? A screening technique for colonists to test the bonds and compatibility of future colonist couples. I found the premise compelling (how each couple would behave in a series of crises a colony could experience) but the imaginative sequences lacked vividness. Perhaps the result of writing a story around a supplied piece of art? All the elements had to appear in her story!

“Whoever You Are” (1952), 3/5 (Average): Previously reviewed here.

A space opera with a fun twist…. A vast web encircles the solar system manned by the intrepid men and women who are still seduced by the allure of space. The bravest souls—called Byrds—fly from the energy womb off into the bleak expanse setting up colonies, encountering aliens. One of these spaceships returns but the crew is dead, and aliens are on board. Thankfully the ship is encased in the web and does not appear to be a threat. Via the ship logs of the various dead crew members the mystery is slowly pieced together. As most of Merril’s futures, women play central parts in uncovering the mystery. But, it might be too late!

“Death is the Penalty” (1949), 3.5/5 (Good), or, coined by me, “Love in the Time of the Cold War.” A memorial to the looming wall, “a Boundary rises white in the sun” (206), tells a sad tale of love in a paranoid era. David encounters Janice while she swims in a stream. He sees her book and knows her profession–a scientist. Janice works at the California Open Labs. She quickly infers that he is higher up, restricted, forbidden to exchange knowledge with those of a lower classification. But he makes a fatal mistake.

Filled with dread and melodrama, Merril crafts a memorable story of a doomed love affair where every word and movement is monitored. A remarkably vivid encapsulation of the American fury at the “secrecy” and “classification” in the early stages of the Cold War (written pre-September 3, 1949 Soviet atomic test and September 23rd announcement to the American public).

“The Lonely” (1963), 3.5/5 (Good) is one of the three “cover stories” in the collection. This story provides a detailed explanation of the background and results of the generation ship explored more than a decade earlier with “Survival Ship” and “Wish Upon the Star.” Human anthropologists intercept a series of “Galactic University” lectures broadcast from Altair on human sexuality (216). The lectures focus on a statue found on Aldebaran VI of a woman holding a spaceship. Terrans, a “newly emerged race” from Sol II, participated in its construction. The history leading up to the dramatic confrontation on Aldebaran VI intersects with the generation ship Survival.

My rating directly reflects my interest in learning the history of the ship, its struggles, its triumphs. As a story itself, I’m not sure Merril succeeds. As a future history of The Matriarchy and a possible outline of a novel that never materialized, it fascinates. At the very least, Merril has her anthropologist voice a snarky comment about the phallic nature of the art the story was required to cover: “Shot of statue […]. I tried women on staff here. They focused more on the phallic than female component” (226).

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

Very nicely, concisely, and fairly assessed works by a woman slipping away from awareness.

Happily I agree with you all around, Dr. B.

Thank you.

While I know you weren’t as enthusiastic as me about “Wish Upon a Star” (1958), I recommend tracking down at least the other two generation ship stories — just see what happens to the crew! Although, both “Survival Ship” and “The Lonely” are lesser works.

Excellent post and some wonderful illustrations there. I’ve only read one of Merril’s stories but I rated it highly and keep meaning to explore her work further. I don’t know why she’s not better known (or do I???)

Thanks for stopping by. Which of Merril’s stories did you read?

“Dead Centre” – it was in one of a pair of anthologies I reviewed for Shiny New Books here: https://shinynewbooks.co.uk/moonrise-lost-mars-ed-mike-ashley

Ah, now memories are coming back. We’ve discussed Dead Center before. I reviewed it as well in Out of Bounds — and called it a masterpiece.

https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2015/07/05/book-review-out-of-bounds-judith-merril-1960/

It is better than the stories in this collection. BUT, the three generation ship stories here might be worth reading. The parts of a novel she never ended up writing!

Indeed we have. And I’m still keen to explore more of her work, even if it isn’t up to Dead Centre standards! 😀

Yeah, I think the best purchase is the omnibus of her solo-written SF stories that I mentioned above. It’ll also contain some of her best known tales like “Daughters of Earth” (1952), “That Only a Mother” (1948), etc.

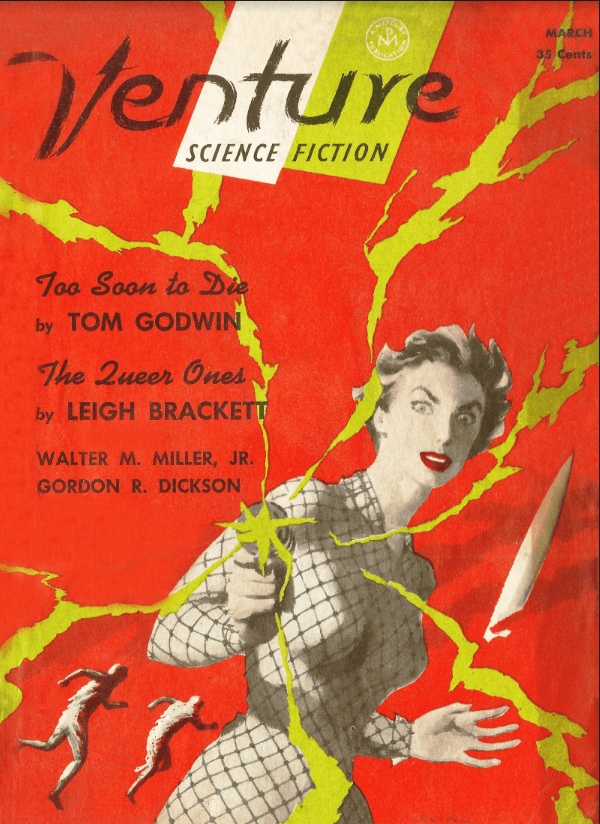

I’ve only read a couple of these stories, I’ll have to see about finding some more. I have to admit I thought “The Lady Was a Tramp” absurdly sexist, and I was quite surprised to learn that “Rose Sharon” was actually Judith Merril. (That issue of Venture does have one oustanding story, Brackett’s “The Queer Ones”.) “The Deep Down Dragon” is decent work, however. (Reminded me a bit of perhaps Kingsley Amis’ best SF short story, “Something Strange”.)

If you’ve reviewed any of her stuff on your site, feel free to link it!

When I read “The Lady Was a Tramp” a few years ago, I was struck the same way.

I recommend the three generation ship stories (“Survival Ship,” “Wish Upon A Star,” and “The Lonely”) — fragments of what would could have been a fascinating generation ship novel!

I wanted to like “The Deep Down Dragon.” I’m always intrigued by the idea of psychological testing for future colonization. But it lacked something…

As I mentioned to Kaggsy above, her best work I’ve encountered so far are “Dead Center” and “Daughters of Earth.”

James Davis Nicoll seemed to enjoy her novel Shadow on the Hearth (1950): https://jamesdavisnicoll.com/review/just-a-little-rain

Here’s my post for her birthday last year: https://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2020/01/birthday-review-stories-and-book-review.html

I just revised it, by the way, to soften my somewhat dismissive look at the stories I review there by noting that I haven’t read her best work, and adding a list of the stories you recommended.

(I’ll definitely get to “The Shrine of Temptation” — I’m trying to read as many of Cele Goldsmith’s Fantastic/Amazing issues as I can!)

For a story that is not actually about psychological testing for future colonization, but that almost could be because it’s about a simulation of a colony situation, and which I think is one of the best stories of the past half-decade, you could try Genevieve Valentine’s “Everyone From Themis Sends Letters Home”, collected in my 2017 best of the year book, but also available free at Clarkesworld. (I know — 2016 is pretty late for you!)

There appear to be multiple versions of “The Shrine of Temptation.” I read it in this collection vs. the original magazine.

I also listened to Judith Merril READ the story which was really fun. However, she seems to be reading a different version (maybe the magazine original?)–sections are moved around and some basic phrasing changed.

Because I just found this link, here’s the post where I originally wrote about “The Lady Was a Tramp” — a review about the issue of VENTURE in which it (along with Leigh Brackett’s excellent “The Queer Ones”, and Tom Goodwin’s fun old-fashioned romp “Too Soon to Die”) appears. (Maybe avoid the comments, though!) From back in 2012: https://www.blackgate.com/venture-march-1957-a-retro-review/

It’s a historical footnote now, but VENTURE was an above-average magazine that published a lot of the better late-1950s efforts from Sturgeon, Kornbluth, Budrys, Miller, and the like.

In general, it might have become the flag-bearer for an American counterpart movement for a better-written, more adult SF, somewhat equivalent to what the British New Wave would actually be when it emerged in the latter half of the 1960s.

Unfortunately, VENTURE launched at an epically bad time, in the last two years before the collapse of the American SF magazine distribution ecosystem when the American Magazine Corporation vanished. (Though, yes, there was an attempted revival of the mag in the late 1960s.)

Yes, that was a terrible time to start a magazine. (Pohl tried to turn STAR into a magazine at the same time, it lasted one issue. (Had a great Chan Davis story, and a strong early Brian Aldiss story.))

I think some of Venture’s attempts to be “adult” — Poul Anderson’s “Virgin Planet” for one, Asimov’s “I’m in Marsport Without Hilda” for another, this Merril story as well, possibly, come off a bit almost sniggering. A bit juvenile. But, yes, overall the 11 1950s issues published some striking stuff — a few strong Sturgeon stories, “Two Dooms” by Kornbluth, “The Queer Ones” and “All the Colors of the Rainbow” by Brackett, Davidson’s “Now Let us Sleep”, some good Budrys stories (especially “The Edge of the Sea”.) A “Best of Venture” book would be really good.

By the way, I’m planning to write something about the November 1957 issue, especially Sturgeon’s “It Opens the Sky”, sometime fairly soon.

Thanks for the magazine background. I must confess, that is an area where my knowledge is lacking.

I look forward to exploring more of its issues.

Rich, those comments… I can’t. haha.

Thank you for including the background of VENTURE in your review. I did not know that it was a companion volume of F&SF.

Pingback: #MonthlyWrapUp: February 2021 – Curiouser and Curiouser

By the way, I just realized, in looking through Venture TOCs, that Merril used the “Rose Sharon” pseudonym one other time — the issue of Venture just previous to the one with “The Lady Was a Tramp”. It’s for a story called “A Woman of the World”, which was published paired with Les Cole’s story “A Man of the World” as a diptych called “World of the Future”. So maybe she just stuck with “Rose Sharon” as her “Venture pseudonym”. Or maybe “The Lady Was a Tramp” is set in that sanme “World of the Future”, though I doubt it.

Rich H. wrote: ‘I’m planning to write something about the November 1957 issue, especially Sturgeon’s “It Opens the Sky”’

For BLACK GATE? I’ll keep an eye out for it.

Yes, for Black Gate. In a few weeks. Just today my latest post there is up, by the way, on John M. Ford’s “Winter Solstice, Camelot Station”. https://www.blackgate.com/a-great-fantasy-poem-winter-solstice-camelot-station-by-john-m-ford/

“A Woman of the World,” as you point out, the only other short story under the Merril pseudonym, seems to have been infrequently anthologized. I’m even more tempted now.

Mark: I’m not sure I’d call Merril story juvenile (despite its lack of success in Rich and I’s view — he might disagree). I am interested in reading a feminist take on the story. Could it be argued that the story is about a woman taking her sexuality into her own hands? I’m not sure (especially as it comes off in a very 50s way). I want to read more interpretations of the tale.