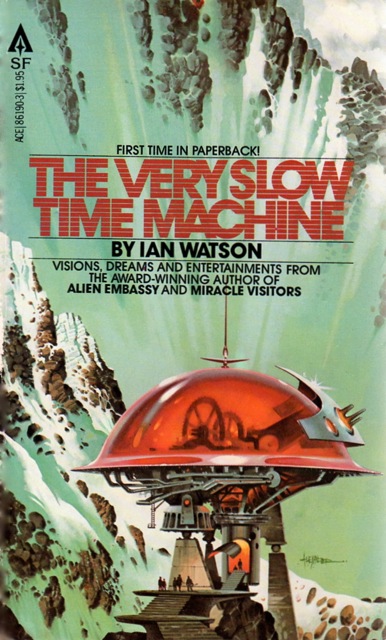

(Paul Alexander’s cover for the 1979 edition)

4.5/5 (Very Good)

My first exposure to Ian Watson’s extensive SF catalog could not have been more impressive. The Very Slow Time Machine (1979) is up there with Robert Sheckley’s Store of Infinity (1960) and J. G. Ballard’s Billenium (1962) as the best overall collection of stories that I have encountered in the history of this site.

The collection is filled with narrative experimentation (“Programmed Loved Story,” “Agoraphobia, A.D. 2000,” etc), some awe inspiring ideas (“The Very Slow Time Machine,” “The Girl Who Was Art” etc.), a few delightful allegories (“Our Loves So Truly Meridional,” “My Soul Swims in a Goldfish Bowl”), and a handful of more traditional SF stories that hint at anthropological themes (“On Cooking the First Hero in Spring,” “A Time-Span To Conjure With” etc).

Inspired by Watson’s personal experiences teaching English in Africa and Japan, most works are frequently infused with non-Western characters and locals. The blend is heady, stylistically acute, and highly recommended for fans of literary SF. Thankfully, I have his first two novels—The Embedding (1973) and The Jonah Kit (1975)—unread on the shelf.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis

“The Very Slow Time Machine” (1978) 5/5 (Very Good): Nominated for the 1979 Hugo Award for best short story. Frequent readers of my site will have noticed my general dislike for time travel stories. However, Watson’s “The Very Slow Time Machine” has become one of my favorite of the sub genre. The Very Slow Time Machine (VSTM) appears in an unoccupied space December 1985 at the National Psychical Laboratory. As time progresses forward the occupant–initially “ragged and tattered as a tramp: as crazy, dirt, woe-begone and tangle-haired as any lunatic in an ancient Bedlam cell”—of the Time Machine grows “saner and more presentable” (2). How exactly time works for the Time Machine and its occupant is slowly revealed over the decades—and the occupant’s position slowly becomes Christ-like figure for those that observe him through the glass.

“Thy Blood Like Milk” (1973) 4.25/5 (Good): A few of Watson’s stories tread a fine line between the overly baroque and more restrained shows of power. Unfortunately, “Thy Blood Like Milk” is the biggest culprit in this collection of the former category. The story relates the journey of an adherent of Aztec ritual and belief who braves the horrific elements of a horridly over-polluted future in search of glimmers of the sun. Along the way he is captured by a woman named Marina who sadistically siphons his blood while encased in a hospital along “Superhighway 31” (34). Despite the story’s flaws, its a powerful mixture of sacrificial ritual, virulent pain, and desperate quest in a decaying world.

“Sitting on a Starwood Stool” (1974) 3.25/5 (Average): The least of the collected stories is a tale of obsession. The object of the obsession is starwood harvested from a “trees” that “quarry metals from the rocks” of a planetoid called Toscanini (72). At the perihelion of the planetoid’s orbit the trees “bake” and suck up the sun’s power. Every orbit results in a new layer of metal. The starwood is more than an object of incredibly beauty—it radiates healing powers for those who sit on it. But, the fearsome Grand Monk of the Yakuza sits on the stool. The narrator recounts his attempt (and horrific results) to steal the rarest object in the galaxy. Fun. Simple.

“Agoraphobia, A.D. 2000” (1977) 5/5 (Near Masterpiece): A mysterious and delightfully obtuse story about a Japanese astronaut, Yamaguchi, who is forced to commit suicide in normally sealed and “sole remaining open space in the Tokyo megalopolis” (82). The Space Agency measures his “leaping pulse” for the “benefit of Space Science.” As he moves slowly through the open space in his suit he is beset by agoraphobia — “the background boom of the City was the grinding of the globe as it turned beneath him like a giant’s clockwork toy […] He was a giant perched on a tiny glove, terrified of falling off into endless space […] He felt the desperate need to take over in the tunnels of the City” (85). The best of the collection.

“Programmed Love Story” (1974) 4.75/5 (Very Good): A fascinatingly experimental series of nestled stories—programmed variations on a theme—in a variety of futuristic visions of Japan. The programmed variations revolve around the woman Kei who works at the Queen Bee cabaret. In one, a businessman falls in love with Kei only to discover, in a world where successful business have astrology computers, that her “palm print is incompatible with his” (89). In a much more sinister variation, the Queen Bee has installed “a Suggestibility Wizard & Rapport Machine” that chooses from hundreds of faces and personality types that are then imprinted on the prostitutes for customers. Although somewhat elusive, the story if beautiful and strangely disturbing, the ending is perfect: and it suggests so much more.

“The Girl Who Was Art” (1976) 5/5 (Near Masterpiece): My second favorite story in the collection, “The Girl Who Was Art” posits an art movement in a future Japan where women perform the art for their own bodies for “guests”, for example “The Gratitude of Aeschylus”: “Like a ballerina on tiptoes with legs wide apart I shall have to stand, pointed toes concealed in blue rubber mermaid fins that cling to my legs as far as the knees. Apart from a red Noh masked taped to my crotch, my only other article of dress is a diving helmet with abnormally broad glass window” (99). The combination of performance art, often sexually explicit, with “guests,” and Masters who order them to perform generates a current of profound unease. The women are cast off as soon as trends change: and a new avant-garde art form is on the horizon, The Grid. The Grid selects a random two-meter square portion of the city and projects it on the wall of “discerning homes.” Each two-meter square “is what it is” i.e. “TOTAL REALITY” (106).

A beautiful, sinister, rumination on art and performance. Highly recommended.

“Our Loves So Truly Meridional” (1975) 4.5/5 (Very Good): A powerful, if slightly saccharine but moving, SF allegory… On the verge of a war great “glass” barriers divide the world “like an orange” (107) along various longitudinal lines: “it’s not actual glass. Thought it looks like glass and feels like it to touch. Some forcefield, they say” (108). New political entities are formed, the old powers disintegrate. Families and lovers are, literally, broken apart by the appearance the the translucent walls: “A inexorable force squeezed us apart. His hand became rubber then jelly and slid away to join the rest of his body over there” (112). A few still communicate through the glass via signs… Beautiful.

“Immune Dreams” (1978) 4/5 (Good): Adrian Rosen, a cancer researcher, has strange premonitions of his cancerous demise after participating in experiments at Thibaud’s sleep laboratory. Despite the protestations of his research unit, Rosen buys into Thibaud’s bizarre research, which has, to this point been performed on cats: “from each cat’s shaven skull a sheaf of wires extended to a hypermobile arm, lightly balanced as any stereo pick-up, relating the electrical rhythms of brain […]” (127). Rosen wants to be his next experimental subject…

“My Soul Swims in a Goldfish Bowl” (1978) 4.5/5 (Very Good): “And at last, at last, this morning I do cough up something. Something quite large. Rotund, the size of a thumb nail. It lies squirming on the white enamel. Phlegm alive” (141). An allegory on the decay of a relationship… The man’s wife remarks that she knew his soul was “narrowing and congealing” (143) for months, little surprise that it ended up in the sink. Strangely sinister scenes unfold, dinner guests giggle around the bowl with his soul swimming inside… An empty malaise permeates. Terrifying.

I talked briefly with Ian Watson about the story and he pointed out that there was a French film adaptation in the works! Unfortunately, the project did not go through and all that exists of the project are a few stills.

“The Roentgen Refugees” (1977) 4/5 (Good): A rumination on race and society in a future South Africa after an unexpected astral effect wipes out all most of the non-white inhabitants of the world. The narrator, unabashedly racist, and a group of other characters (including an Indian), journey across the landscape (often covered with the skeletons of the dead) in a military half-track. The encounter a ragtag group of adherents of the Church of Abandonment who believe the chosen ones were those the astral effect wiped out—while God abandoned everyone else…

“A Time-Span to Conjure With” (1978) 3.75/5 (Good): A colony ship sets off to seed multiple planets. On their return to a planet they seeded forty years earlier they expect to find a thriving community along the coast. Instead, they discover a small community at the “very heart of the largest continent” (167). Are there ecological reasons for this unexpected development? Or perhaps some strange machination of the seemingly tame “primitives,” i.e. “puckish ‘human’ dragonflies” (169)?

“On Cooking the First Hero in Spring” (1975) 3.25/5 (Good): In this future practitioners of traditional sciences are not the only ones explore the galaxy. When an expedition arrives on a planet in habited by “Clayfolk” i.e. “upright, bifurcate slugs, with bodies that stretched and contracted as they walked, producing a curious undulating pogostick effect” with pseudopod “fingers” (190) a bizarre alien ritual proves stupefying. Why exactly is a random “Clayfolk” seized every day, covered with clay, and baked (with a tube inserted at each end) in a fire? The hard “statue” containing the slug that remains is placed at the entrance of the Clayfolk village. Lobsang, an adept at Tibetan rituals, develops an explanation… But then again despite the rationale behind it all, perhaps the real meaning remains as alien as the “Clayfolk.”

“The Event Horizon” (1976) 3/5 (Average): A spaceship, the Subrahmanyan Chadrasekhar, takes its scientists and crew to the lip of a Black Hole: “even the fabric of space was missing, there” (207). But, there a living being inside! The discovery was possible due the growth of “Psionics Communication[…]” a “telemedium system” (208). “Instantaneous psi-force along could enter a Black Hole and emerge again” (208). A hokey story that almost feels like a pastiché (the spaceships travel via psionic and sexual energy) of more metaphysically SF that lacks the trademark beauty of many of Watson’s other creations. The least intriguing of the collection .

For more reviews consult the INDEX

(Karel Thole’s cover for the 1980 edition)

(Tevor Webb’s cover for 1981 edition)

He’s a man of wonderful ideas and a great sense of humour. The early novels are a little wordy and academic but, when he hits his stride, there’s a great transparency about his prose and an elegance about the way in which he delivers the ideas. As this collection shows, he’s often at his best at shorter length but, among the earlier novels, have a look at Alien Embassy, God’s World and Deathhunter. In the spirit of openness, I should declare an interest in that we went to the same school so I have known him on and off for decades.

I think I’m going to tackle his 70s novels first — The Embedding and Jonah Kit. As for “academic,” that doesn’t always bother me… we shall see.

Yes, he seems like a really nice guy. I’m talked to him briefly on twitter about the short film some French director was making adapted from one of his stories. Unfortunately the project didn’t go through.

Ah, The Embedding. Not his most accessible work.

Eh, that’s ok! I read tons of inaccessible works (and not just SF).

That’s actually why it’s so appealing!

If you can find a copy of “The Book of the River”, it is a great read as well!

I’m a big Ian Watson fan, or was anyway when I read more SF. His UFO book was spectacular, and he had a novel about psychics being used to communicate with aliens (though there’s more going on it turns out) which again was just tremendous. He’s an underappreciated talent.

Alien Embassy, that’s the second one I was referring to I think – I somehow didn’t see the comment above initially.

I’ll stick with his 70s stuff for a while — but those are on my radar.

Damn, another hardcopy book I need to buy! Nice enticing review.

Haha, thanks!

Ian Watson is a name that just never caught on in the US, and as a result, he never got the exposure he fully deserves. I’ve only read his ‘famous’ novels, but the collection looks great – including the intriguing title.

I wonder why he never caught on in the US…..

Which ones did you read?

The book sounds great, and as you know I am a fan of short stories. However, and I imagine this is no surprise, it is that cover by Paul Alexander that really “wow’s” me and makes me anxious to track down a copy of this book.

Yes, it is one of Alexander’s better ones. Not sure it relates to any of the stories though…

Well, you’ve convinced me to buy the book.

Hopefully it’s as satisfying for you as it was for me 🙂

Reblogged this on TRISKELE PRESS and commented:

So impressive, I would republish a hard copy for my self!

The review or the book itself? (slightly confused. Have you read it?)

His first five novels are interesting. The first three are thematically similar. Alien Embassy is about Buddhism and some interesting moral questions in social manipulation. Miracle Vistiors is the UFO book. Another interesting idea. Read it back in the late 90s.

Hello Mark, this review is from 2014 — I’ve since read The Embedding and The Jonah Kit. I enjoyed both. Unfortunately, I never managed to review them. Alas.

Well Martian Inca is next but in some ways it is more of the same. It has the idea of racial memory a la the Dune books. Alien Embassy and Miracle Visitors are good different. Clute wrote that Watson and Frank Herbert were the main explorers of intelligence and alternate states of consciousness. Watson was aware of Herbert. Have you read Dream Makers by Charles Platt? You would really enjoy that. There is a good interview with Watson. He said something insightful about Herbert. He had complex ideas in cops and robbers plot. Which was my same sense of Dune. If you want a guest review I would be glad to do some reviews.

Mark

I have read some of the interviews in Dream Makers. I can’t remember if I read the Watson or not.

Thank you for the offer. Unfortunately, I’ll have to decline. My site serves as a research apparatus and memory device for my current projects. The occasionally guest reviews I have in recent memory (for example, with Rachel S. Cordasco) follow threads I’m currently exploring and are rare and far between.

For more recent explorations on the site, check out my 2024 and 2023 in review if you haven’t already!