The following review was originally conceived as the fifth post in my series on “SF short stories that are critical in some capacity of space agencies, astronauts, and the culture which produced them.” However, it does not fit. It is a spectacular evocation of memory and triumph and worth the read.

Thank you Mark Pontin, “Friend of the Site,” for bringing it to my attention.

Previously: Katherine MacLean’s “Echo” (1970)

Up next: Theodore L. Thomas’ “Broken Tool” (1959)

5/5 (Masterpiece)

Theodore Sturgeon’s “The Man Who Lost the Sea” (1959), nominated for the 1960 Hugo Award for Best Short Story, thrusts the reader into a seemingly delusional landscape, generated by extreme trauma, of narrative fragments. One thread follows a child as he presents increasingly complex toy spacecraft to a sick man trapped in the sand. In another instance, an accident at sea becomes a transformative realization that fear can be overcome. All the threads coalesce into a remarkable distillation of post-Sputnik (1957) triumph and clarity.

As it is short, go read it first before you dive into the rest of the analysis!

Of Memories, and How They Spin our Threads

In our narrator’s (N) journey to re-awareness, he must conquer the amoeba of terror that envelops his shattered body in the wreckage of the first Mars lander. Sturgeon positions our memories (recalled as disjointed yet meaningful scraps) as the threads that rebind our tattered holes. The memories are both snapshots of individual moments (watching Sputnik in the sky) and entire cohesion generating processes (a voyage to sea and its aftermath). While an incident in the past might have been “beginning of the dissection, analysis, study of the monster” that is fear, “It began then; it had never finished” (159). N, in his state of shock, must complete the process.

At first narrative confusion, like the moment after a concussion, proliferates. As N’s memories fall into place, their lessons recrystallized, he emerges from sands and all the stories converge.

The Measurements of Death

“Then the valley below loses its shadows, and like an arrangement in a diorama, reveals the form and nature of the wreckages” (163).

“The Man Who Lost the Sea” reaffirms, in evocative and emotional strokes, the underlying ideals of the space program. In his final self-appraisal, N represents the drive that propelled the first satellites into the skies. N’s death is triumphant one. N pulls together the strands of his life, muscles himself to awareness, conquers his fear, measures his worth, and in his last breadth erupts a pithy declaration of technological triumph.

Two other astronaut deaths serve as useful comparisons: Katherine MacLean’s “Echo” (1970) and Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s “Death of an Astronaut” (1954).

In MacLean’s vision, a spaceman dies after an accident where his rocket harms the sentient surface of a planet that triggers a telepathic defense mechanism that bores into his mind. Later he dies unable to emerge from the psychological horror he experienced. He certainly does not regain awareness and place his life as a culmination of scientific triumph à la Sturgeon’s hero. We can only watch as the end narrows in. The death in MacLean’s story is void of triumph. The focus rests on its emptiness/accidentality.

In Miller, Jr.’s “Death of An Astronaut,” his spacer dies bedridden in a run-down home refusing to acknowledge how his choices have impacted his descendants. Or, he realizes that the fantasy he has constructed about his self-value is the only thing that will bring him comfort in his final hours. And the fantasy is preferable to the terror of a wasted life.

The measure of death in “The Man Who Lost the Sea,” as tabulated by narrator and reader, yields a positive and objective truth. The memories, jumbled by the haze of radiation, fit together. There was a purpose to it all. There are no missing pieces.

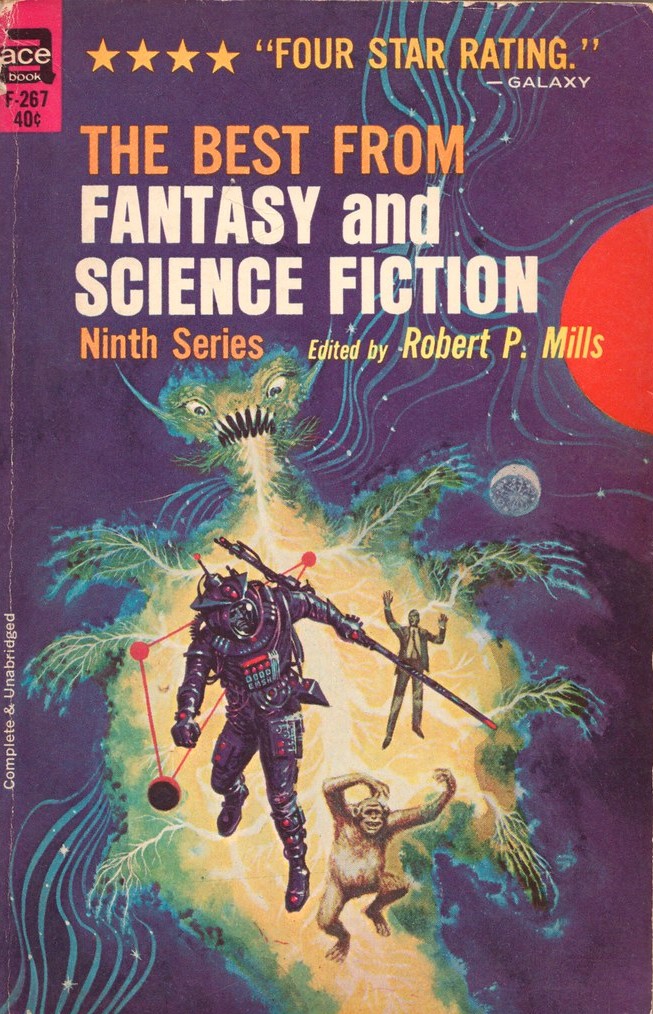

Ed Emshwiller’s cover for the 1964 edition of The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction: Ninth Series (1960)

Herb Mott’s cover for the 1st edition of The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction: Ninth Series (1960)

For more SF reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Thank you,Joachim.What a neat thing to do.Saves looking on Internet Archive.

Pat.(Auckland NZ)

Hello Pat, thanks for stopping by.

Have you read the story? Or are you planning on doing so via the link I provided?

Hi Joachim..downloaded the story then found it’s in my copy of “Selected Stories of Theodore Sturgeon”🤭So will savour it tomorrow.

Pat.

Ah, no worries!

Definitely one of his more anthologized ones — and for good reason. I read mine in the Alpha 8 anthology.

I look forward to your thoughts.

It’s evening here and after reading all day I “do” my emails.That’s why reading tomorrow.

Night.🌞

I’ve heard your injunction to read first & shall obey before absorbing your analysis.

I await your thoughts on the tale with bated breath.

Take the bait out your mouth, I reviewed it 4*s-worth:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/3811857052/

Glad you enjoyed it!

I’m with you on the levels of immerse Sturgeon accomplishes — the seasickness (had to look up “proprioception” in your review!), traumatic impact and confusion, being trapped…. And, how a man deeply trained in the sciences, might find a dataset as an anchor point to pulling oneself out of the concussive state.

…and just in time…that was the ending I most wanted to see. Pitch perfect!

The twist ending was unexpected, the writing aptly represented the narrator’s circumstances in retrospect with a few autobiographical details, but I’m one of those people that is unable to articulate why I dislike Theodore Sturgeon’s stories other than there’s always a sense of something disturbing underlying his words.

I absolutely think his semi-stream of conscious way of writing and use of second person can be bewildering(yet, in this instance, immersive). I thought the “twist” (maybe?) pulled everything together in an effective and affective way. Up to that point, I found it an unsettling peek into the mind of a traumatized victim.

Do you think the story was critical of the space program? Or, is the disturbing element the way the narrator’s character (fears and traumas) traits are laid bare?

As almost all 50s short story authors, he can be hit-or-miss. Sturgeon, despite flashes of brilliance, certainly writes duds! Check out my review of his collection A Way Home (1956) is you haven’t already. https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2013/11/24/book-review-a-way-home-theodore-sturgeon-1956/

The twist pulled everything together so the body of the story made sense. Given the choice, I’ll go with it’s just that baring his soul through fiction with a few nice phrases is what I find disturbing as opposed to criticism of the space program.

I’ve also read in order, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, The Hurkle is a Happy Beast as part of Conklin’s The SF Galaxy, Venus Plus X (twice), Caviar, More Than Human and The Cosmic Rape. With the exception of Voyage that I read near original publication date of 1961, I’ve just never cared for Sturgeon.

I quickly read the link. I probably won’t bother with any more Sturgeon acquisition except what’s included in 50s emagazines.

I found the story emotionally intense — for me, that’s a flower in his cap. But yes, as you saw from that linked review, I struggle with a lot of his short fiction. I enjoyed More Than Human (albeit I read it when I was 18) and Venus Plus X but DESPISED “The Hurkle is a Happy Beast.”

re Katherine MacLean’s “Echo,” in Infinity One:

https://archive.org/details/Infinity_01_Infinity_One_1970_siPDF/page/n5/mode/2up

Thanks! Didn’t realize so many of the original anthologies had been digitized.

Thoughts on the story?

Joachim,this is from the Open Library I mentioned. It’s a treasure trove if you haven’t experienced it yet..or the Internet Archive.

I came back to SFF after forty years!..using these two resources to catch up.

Pat.(NZ)

I use the Internet Archive all the time for magazines. As I tend to purchase anthologies and collections, I hadn’t investigated outside of magazines.

But yes, a wonderful resource.

As actual books are scanned the quality can be spotty.So I’m tending to buy Garner Dozois’ backlist. But there are more than enough books to see me through!

Pat.

Ever get around to reading this story?

Not yet..I followed the discussion and thought your last comments reflected the dangers of analysing a piece of writing to death!So much of it comes down to personal interpretation based on one’s own values and interpretations and value placed on broader things like dreams…

The story fits into a series of fictions I’m exploring about the death of the astronaut so I will discuss all elements of it with those who stop by — I tried to warn you in the original review with the “stop go read it” comment — haha.

Joachim..I shall read it as soon as I’ve put my washing out. Earthly/earthy/mundane concerns remain.

Public Holiday today and though I’m retired still treat holidays and Sundays as special.i.e.do what I like.

Pat.

You don’t have to do anything! You just said you were so I thought I’d follow up 🙂

And in my view there are zero dangers in “overanalyzing” a story… it triggers discussion and interpretation! That’s only a good thing.

It’s written in a tense and compelling prose, but is also oblique and challenging. I’ve read a fair number of Theodore Sturgeon’s short stories in the past, but is different to almost anything else I’ve known by him.

It is definitely challenging but I did not find it oblique (At least by the time I got to the end). Especially as all the threads are spelled out at the end.

What would you argue his message is? Do you think I’m correct suggesting it’s entirely positivist (as embodied by his final words)?

If you mean that his situation is inescapable, I suppose it is.

It might be inescapable, but it’s still triumph – and he’s conquered his fear and fulfilled his destiny and dreams (the child’s dream of space travel).

Yes, I suppose he realises that his dream is an unromantic one, but is fulfilled because he accepts the truth of his situation.

Is it unromantic? He’s the first on Mars!

Wait, are you talking about his voyage to the sea? I think that’s there for another reason. That’s the moment where he was confronted by his fears and started the process of conquering them. And, his crash on Mars allows him to finally conquer the deepest fear of all, the fear of death and failure.

We don’t always agree, but this Sturgeon tale is a gem. Indeed, I gave it the Galactic Star for best short story of 1959!

If folks want to see what pieces that story was flanked by, here’s my review of the whole issue (one of the very best F&SFs ever):

https://galacticjourney.org/sep-5-1959-the-best-october-1959-fantasy-and-science-fiction-1st-part/

Thanks for the link.

But yes, I enjoyed Sturgeon’s process towards lucidity…. I’m not always a fan of his fiction, but the kaleidoscopic deluge we’re presented with falls gorgeously into place.

I want to like this story more than I do, but I don’t. Maybe it’s because most everyone else does!

I think second person is hard to pull off, and since the publication of Sturgeon’s piece this voice has been overwritten massively by the choose your own adventure franchises. From the outset, while being placed in the hot seat, I feel as if I’m waiting for a choice to be forced upon me: “If you want to find out more about the gyroscopic effect of helicopters, turn to page blah…”

In terms of the story itself the second voice sort of makes sense, but also sort of doesn’t. I can’t escape the feeling that this is supposed to be, ahem, a work of Literature. This heavy handedness has most likely been attenuated somewhat since its publication, considering the trajectory of sf since 1959, and the endless—albeit mostly settled—debates about whether or not sf can be considered as serious literature. But it’s there. A lot of Harlan Ellison’s work from later in the 1960s has this feel, and whereas sometimes it produces good work (I do like the Sturgeon short, really!), the debate itself is one I find tiresome—even and especially when it may have mattered (like back then).

I’m not sure what else to say. I like it… and I don’t!

I agree that second person is hard to pull off. Usually I put down such experiments as unreadable: here I didn’t.

I thought I’d be bothered by “the gyroscopic effect of helicopters” but then I thought about what would pull someone like our narrator out of a traumatic moment — datasets, technical details, demonstrable mathematical truths… So I wasn’t bothered.

I enjoyed the story perhaps most as a point of comparison with the other stories I’ve reviewed in this series. While the positivism isn’t necessarily what I’m looking for, I found it a totem of (as I say in the review) post-Sputnik triumph. As a window into that moment told in a gorgeous way, Sturgeon succeeds.

AND, serious attempts to tackle trauma and memory that don’t come off as trite are appreciated.

And that’s why I liked the story.

I’m going through one of my habitual phases of hating literature.

The first paragraph almost doesn’t work–it’s awkward. I vaguely recall trying to read it once or twice years gone by and faltering on it. Sturgeon wisely chooses to use the second person voice sparingly in the rest of story. Though I’m not against it, or even those attempts to write entirely in the second person (though only French examples come to mind, notably Georges Perec’s excellent Les Choses). It’s just an awkward start, slow to come together.

Do you think that the narrator’s death is truly “triumphant”? I feel there is enough ambiguity here, at least from Sturgeon’s perspective as opposed to the narrator’s presumably positive engagement with the conquest of space. I want to read it as the death of the imperialistic dream initiated by Sputnik, rather than an unfortunate bump on an otherwise smooth cosmic exodus (I can’t help but think of the pollyana-ish nonsense being babbled by Elon Musk’s henchmen as yet another rocket goes bang…).

But perhaps this is too much to ask of Sturgeon?

Maybe a better way of thinking about the “triumph” is more whether it was triumphant for the character? I think the character, of course approaching death, sees his impending doom as a culmination of his life and a worthy death. Considering the deaths of relatives I’ve been close too who blamed those around them and the choices they made in the distant past to their bitter end, this one comes off as at least as self-justification that matches the rhetoric of 50s scientific triumph (even if I struggle personally with this type of rhetoric).

Incidentally, I love that first paragraph! “Say you’re a kid …”

The first paragraph is my least favourite of the story. It picks up after we get it out of the way!

I also loved the first paragraph.

I can see how it would be triumphant for the narrator. Even though he’s dying, “at least I got here!” he could think. Even the hallucinatory flashbacks are a sort of secular stations leading to the cross of his death on the cavalry of Mars (phew!). Still, I’m going to privately read it as the death of the dream of conquest!

Or, like the first fish with rudimentary legs on Earth’s shores, but the first step in the dream of conquest!

My first thought..after bursting into tears,such was the build up of grief and terror,was that Charlton Heston pinched the last line of Planet of the Apes from the last line of this story. Rather than triumph,I wonder if that last thought was sarcastic…as if anything could make up for dying in such a rather ignominious way.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I’m glad the story has spurred so much discussion. And varying interpretations (although I’ll stand by my more positivist take — haha)…

And, of course, if you choose to read any of my other installments in the series, I look forward to your thoughts then as well!

Made a note of your new recommendations. Think it’s excellent to be made to think more deeply about fiction rather than gobbling it down like so many bad carbs!

Sounds like plan! I don’t know if you saw it or not, but you might find this productive in identifying some recommendations (there’s a short story and novel section)!

https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2021/01/01/updates-my-2020-in-review-best-sf-novels-best-sf-short-fiction-and-bonus-categories/

JB wrote: And, his crash on Mars allows him to finally conquer the deepest fear of all, the fear of death and failure.

Not that the narrator’s got much choice there.

Granted, a dying astronaut in denial that’s he’s dying is possible, though the test pilot types who stocked the U.S. space program were hard-grizzled realists about the likelihood of system failures aboard the craft they flew. (There’s an audio-recording of one pilot calmly running through a check-list of his plane’s failed systems one more time with flight control, which gets cut off in the middle as his plane hits a mountainside.)

Still, that would be a different story — one that Barry Malzberg has probably written more than once – all about the Wrong Stuff. Sturgeon does something different.

You’re framing the achievement of “The Man Who etc.” using the critical language of appreciation that we’re all trained to use with regards to the modern literary short story. To be reductionist, we’re taught to understand literary artistry as being essentially the creation of a machine for delivering a more or less transformative epiphany to its protagonist at the story’s payoff – thus, you write, “his crash on Mars allows him to finally conquer the deepest fear of all, the fear of death and failure.” From this transformative epiphany, additionally, if the writer is really good something about the human condition more generally may be adduced; Joyce’s ‘The Dead,’ is the supreme example of the literary short story as an ‘epiphany machine’ (‘Snow was general all over Ireland…’.).

All this is fine. And Sturgeon’s “The Man Who Lost the Sea” does the things a great modern literary short story us supposed to do. Transformative epiphany; check. Some greater truth adduced about the human condition; check. Still, what is the specific ‘greater truth about the human condition’ that Sturgeon presents or suggests with his narrator’s epiphany?

I’d claim it’s something different than a mainstream literary short story would be likely to – or maybe even could — suggest. If science fiction’s central foundational myth isn’t the Dream of Spaceflight, it’s certainly one of its foundational myths and it’s the subject of “The Man Who etc.” And yet what’s the Dream of Spaceflight about?

There’s an old John Wyndham fix-up novel called ‘The Outward Urge’ (from 1959). That title nicely sums up, I think, what classical SF’s Dream of Spaceflight was about: the idea that the human race was going to spread out and settle, first, the solar system, then the galaxy.

Was that Dream naïve or even stupid? In one way, extraordinarily naïve. In another way, not at all. When you consider how specimens of one species, the East African Plains Ape, not only trekked out of Africa by land till they’d crossed the planet’s land-masses, but also sailed extraordinarily flimsy rafts, canoes, and coracles across the thousands of miles of blue water ocean of the Pacific and the Atlantic, the mind boggles. What possible reason – and what rational prospects — did those people have to cast off from known land like that? Given that many of them must have died, that an evolutionary drive was one component of our human ancestors’ migrations seems not at all implausible.

And so that’s what Sturgeon’s SF story has to say — that a regular mainstream lit story probably couldn’t — about the human condition. And more than the human condition. At the risk of stating the blindingly obvious – the story is called “The Man Who Lost the Sea,” after all – Sturgeon’s story also is a near-perfect expression of another classic SF move: the astronaut dying on Mars, away from the sea and on the dead sands of another world, is analogous to the first primeval sea creatures that crawled up the beaches on Earth and died there. The human condition of Sturgeon’s dying astronaut is also the evolutionary condition of life itself.

Hello Mark, thanks for the comment.

There’s a lot in your comment so I’ll respond to only a bit.

I must confess, I deliberately dodge on this site discussion of whether a work of SF is a work of literature or vice versa as I am interested in the larger morphology of all SF produced at that moment (of course, I have my favorites and they tend towards more refined tellings). I deliberately want to cast my net wide. I don’t want a mud-slinging experience of “this is real literature” and “this isn’t.” That said, I understand that Sturgeon deliberately added a literary sheen to things. I found myself drawn in, and that receives my stamp of approval especially as it engaged with themes — operations of memory and trauma — that resonate with me.

“Was that Dream naïve or even stupid? ”

Personally, I’m not interested in assessing retrospectively the validity of memories or traumas or dreams. Rather, these stories fascinate me because of what they can tell us about the 50s zeitgeist. The moment Sturgeon occupied. At the time, these dreams had real heft in the official polemic of the day and the individual lives of Americans. And that’s what they’re interesting!

Thanks again for the recommendation!

Stop! That was not a recommendation if you’re referring to my mention of John Wyndham’s ‘The Outward Urge’!

I only cited the title because it so summed up the underlying ideological assumptions of 1940s-60s space-set SF. The book itself is a desperately dated, early-1950s period piece where a family of stiff-lipped Brits conquer space over the generations, IIRC these decades later. Before his ‘cozy catastrophes,’ Wyndham had a pre-WWII career as a pseudo-American pulp writer; the stories in ‘The Outward Urge’ are a sort of halfway-house between his pulp mode and his later one.

Oh no worries. I just pointed out that I have The Outward Urge already on the shelf.

You’re the one who recommended “The Man Who Lost the Sea” — I was just thanking you again, as I did in the review itself.

But yes, I think it would be interesting at some point to read a very straight-forward summation of the basic ideological assumptions of the era as a point of comparison (I’m not expecting great things). As I’ve mentioned before, I do not only read only to find good literature. I read as a historian, to map a moment (and of course, to find some great reads along the way)… I get tons of enjoyment from the act of mapping/exploring, even if I might bash the book itself!

JB wrote: I deliberately dodge on this site discussion of whether a work of SF is a work of literature or vice versa as I am interested in the larger morphology of all SF produced at that moment

I understand that. I, of course, am coming from precisely the opposite place: How do you write fiction about the effects of technological change and new science on human beings so that it’s literature? How did writers do it in the past?

(Something few SF critics talk about is that it’s very apparent in the SF of the 1930s-40s, and still in the 1950s, how much the authors were struggling with the question of ‘how the hell do you write this stuff anyway’? Thus, John Campbell tries importing the mode of H.G. Wells’s THE TIME MACHINE into American pulp SF to write ‘Twilight’ in 1934; other writers import hardboiled rhetoric from Hammett and Chandler in the 1940s; a writer like Algis Budrys imports the rhetoric style of then-contemporary mainstream lit like Graham Greene and Nevil Shute in the 1950s; and so on.)

JB: Personally, I’m not interested in assessing retrospectively the validity of memories or traumas or dreams. Rather, these stories fascinate me because of what they can tell us about the 50s zeitgeist … these dreams had real heft in the official polemic of the day and the individual lives of Americans. And that’s what they’re interesting!

Sure. But it’s impossible to consider the zeitgeist, the official polemic, and the SF of the 1950s without also considering the technological and scientific assumptions they incorporated. When I referred to the validity, naivete, and stupidity of the Dream of Spaceflight, I meant of those technological and scientific assumptions — nothing to do with memories, traumas, or dreams in any general emotional sense.

In other words: the ideas in 1950s SF and the ‘dreams that had real heft in the official polemic of the day’ were derived from the perceptions of those alive then about what might really become possible in terms of new technology and science, and how that would then effect people. SF is not simple fantasy, where absolute physical impossibilities are presented — dragons flying, wizards casting spells, all the rest of the mindless medievaloid tripe — but (ideally) a series of thought experiments about how things might really be. Granted, in reality these are often the thought experiments of adolescent morons.

Sometimes not, though. Part of the strength of Sturgeon’s “The Man Who etc.” is that the staged nuclear rocket he presents is pretty much how NASA was going to go to Mars; the orbits of Mars’s moons are based on what was known in 1959, and so on. The reality-based aspects of the story (to the best of Sturgeon’s ability in 1959) create the ‘lived reality’ of his dying astronaut, helping to make the story literary art.

Even if you’re coming at SF exclusively from ‘the dreams that have heft’ zeitgeist angle — the sociological angle — different decades in SF history and the general culture have different dreams and a different zeitgeist because, obviously, real science and the technological possibilities evolve.

So in the 1960s all the space-set stories assume that once we reach the Moon, we’ll just keep going and build O’Neill colonies in orbit and on Mars, etc. The only SF writer who predicted correctly what would happen was J.G. Ballard, who said; ‘Oh no, we won’t.’

Why did everybody else get it wrong? Well, besides the business model (what’s the commercial payoff for space?), the truth is that human beings can’t survive in the harsh, radiation-suffused environment of solar space for very long. My theory is that in the 1960s the reality of the Apollo program and the Moon landings encouraged the fantasy of easy further expansion into space beyond the Moon. Unfortunately, the Moon is still within Earth’s magnetosphere, which provided protection from solar and cosmic radiation for the Apollo astronauts. The rest of solar space is far more deadly.

The thing is, scientists had a good idea this was the case in the 1950s. The two SF stories from that decade that do deal with the problem of radiation and the harshness of space are Sturgeon’s ‘The Man Who Lost the Sea’ and Cordwainer Smith’s ‘Scanners Live In Vain.’

That’s what I meant about the Dream of Spaceflight as it was presented in much SF (and popular culture) arguably being ‘naive and stupid.’ That’s also why I recommended ‘The Man Who Lost the Sea’ for your series of reviews of “…SF short stories that are critical in some capacity of space agencies, astronauts, and the culture which produced them.” According to my priors – not yours, I know – it does fit. It tells the truth, which is that you, me, and Jeff Bezos would all die out there quite quickly.

Joachim,

I read the story more carefully and it’s evident the narrator walked away from the crash site to where he collapsed to be partially buried in the sand. He mentions nausea which would be consistent with the undetermined dose of radiation, and that is what makes him a sick man. Assuming it’s a large enough dose to kill him rather quickly, I’d also expect to see mention of vomiting, diarrhea, burning pain from blisters/sunburn and possibly a fever from internal infections unless he dies from internal bleeding. I’d imagine this type of death as being pain filled and just doesn’t jibe with the story for me.

Yeah, I didn’t know exactly what to make of him walking away. But I assumed he was walking away but soon would die anyway — despite his ability move away from the physical crash.

One of my favorite SF stories of all time, indeed I think one of the very greatest SF short stories. Apparently condensed from a 25,000 word draft! Some writers are “cutters” — I’m not sure if Sturgeon was habitually (I would guess not!) but he was this time and it was essential. (Kipling was the greatest “cutter” ever, I think.)

Your review is excellent, captures what matters about the story very well. The ending is powerful every time I reread it, but the first time was sheer magic. And, yes, it brought tears. Still does.

By the way, have you done “Kaleidoscope” as a “dying astronaut” story?

Ray Bradbury’s “Kaleidoscope” (1949)?

Tell me more about it. Is it a negative or positive (or somewhere in between) account of humanity’s drive into space? Would it fit my series? Or be a fun accompanying read like this one?

Maybe more of a fun accompaniment? I read it also in THE ILLUSTRATED MAN in my teens, reread it a few years ago. It’s solid, but not awesome … it’s more a sort of meditation on the dangers and beauty of space flight, but not really directly addressing the issues of man’s drive.

My real motivation in mentioning it is that it is probably the “dying astronaut” story most familiar to the general public. (Unless you count songs like “Space Oddity” and “Rocket Man” (neither of which necessarily end in the astronaut’s death but kind of hint at it).)

Sounds like something that I should reread.

As for the more negative takes on the space agency, astronauts, and the culture that produced them, do any that I haven’t mentioned come to mind? I’m especially interested in space travel presented as similar to the experiences of veterans (Edmond Hamilton) — and of course, more direct criticisms of the “cult of the astronaut” (Malzberg).

But yes, as it’s in The Illustrated Man I have read it but a long while back — maybe in my late teens. So my memory of it is very very fuzzy…

By the way, here’s the cover of a completely unrelated magazine from years before Sturgeon’s story, but I think the cover painting is perfect for “The Man Who Lost the Sea” … http://www.philsp.com/visco/Magazines/ASF/ASF_0265.jpg

Yeah, I’ve always loved Gaylord Welker’s cover — the bleak expanse, the lone figure, perfect.

Sturgeon wrote some duds, but he knocks this one out of the park for sure. Stunningly poetic description of the “sea” and its writhing evolutionary lifeforce. I also really liked the (risky) use of the second-person “you,” a technique that places the reader as a character in the story.

For some reason I kept thinking of the passage in 1 Corinthians 13:11: “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” Maybe it’s the way the narrator keeps linking the boy’s “toy” with the spaceman’s “toy”? Sturgeon is so well-read, with poetry and philosophy and science running through everything he writes, I wouldn’t be surprised that some biblical allegory is working in there too.

Hello Adam,

Thanks for stopping by. I enjoyed the sea imagery as well — and the use of second person (not something I always enjoy).

Have any other favorite Sturgeon stories? (I enjoyed Venus Plus X, More than Human, “Slow Sculpture,” and “Bulkhead”)

“Bright Segment” is a really good one, though an unsettling story for sure (cf. “Some of Your Blood” – superb horror/thriller, and unsettling in the same way). Hmm. “More Than Human” is probably my favourite longer work of fiction, but “Bianca’s Hands” is also good, as is “The World Well Lost.” I do have an affection for the symbiote stories – “Perfect Host,” “Tandy’s Story.”

I read and enjoyed More than Human (in the first batch of SF I read in my very late teens). I rarely buy duplicate copies but when I saw Powers’ cover for the 1961 edition — and bought it on the spot. It’s due for a reread.

I haven’t read any of the other short stories you’ve listed. Although Sturgeon’s poorly named but solid read The Cosmic Rape (1958) is based around a creepy symbiote/parasite premise :https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2011/05/27/book-review-the-cosmic-rape-theodore-sturgeon-1958/

“To Marry Medusa” was the novella title of THE COSMIC RAPE. My favorite Sturgeon shorts besides “The Man Who Lost the Sea” are “A Saucer of Loneliness”, “Affair with a Green Monkey” and about half of “The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff”.

Oh, and I should have also mentioned “And Now the News …”, which is right up there at the top.

I meant to add that I’m sure “To Marry Medusa” was Sturgeon’s preferred title, the the book publisher slapped THE COSMIC RAPE on it.

I might add that I believe that “A Saucer of Loneliness” and possibly “The [Widget], the [Wadget] and Boff”, along with stories like “Hurricane Trio”, are mainstream pieces that Sturgeon reworked to add an SF element in order to sell. (Not certain of this, mind you.)

I haven’t explored it in a bit but SF takes on the effects of future media have long been a favorite theme of mine — so I’ll put Sturgeon’s story in the memory palace (oh how I wish I had one).

Kate Wilhelm’s “Baby, You Were Great” (1968), James Tiptree, Jr.’s “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” (1973) Craig Strete’s

“A Horse of a Different Technicolor” (1975), and John Brunner’s “Nobody Axed You” (1965) all come to mind.

I think “Saucer of Loneliness” was the first Sturgeon story I read (in an anthology about “UFOs,” edited by Asimov, I believe). Haunting piece.

Yes, I’ve read that one, though under the title “To Marry Medusa” – maybe not as strong as MTH but, yes, pretty solid as far as alien symbiote stories go.

Yeah, I remember enjoying it as well — although it’s been a while!

I’m not usually a fan of stream-of-consciousness stories–and the grammatical person changes were jarring–but this was a gem. Not what I was expecting when I saw the publication date.

Thanks for participating in a read-through! Sturgeon, as you could probably tell from early comments, absolutely attempted to integrate more “literary” techniques into science fiction. While he isn’t always successful, I though (as it appears you did) he was successful here.

What did you like most about the tale?

“The Man Who Lost the Sea” seems very New Wave to me. In fact, it seems to achieve all the goals New Wave writers proclaimed in their revolution. Was it recognized during the New Wave years as a precursor to what they wanted to do?

I need to read more introductions to New Wave anthologies — I suspect Sturgeon comes up occasionally. I often skip introductions to anthologies (especially of the Harlan Ellison variety).

Loved this story.Such memorable images-the sea,the buried astronaut, the footprints

I agree. Glad you enjoyed it. Do you have any other Sturgeon stories lined up to read?

I’ve ordered Case and the Dreamer

I have that one too. Haven’t read it yet!