A selection of read volumes from my shelf

What pre-1985 science fiction are you reading or planning to read this month? Here’s the November installment of this column.

Last week I wrote a post about Clifford D. Simak’s delightfully inclusive 1971 speech at the height of the New Wave in which he celebrated science fiction as a “forum of ideas” open to all voices. While reviewing the various snarky comments leveled at the movement by “classic authors” like Asimov, a faint memory of James Blish’s own anti-New Wave sentiments tickled my memory. I randomly opened up a book on my desk to figure out a fascinating SF tidbit to start this post, and voilà, the James Blish story.

Jacqueline Foertsch’s Reckoning Day: Race, Place, and the Atom Bomb in Postwar America (2013) contains a sustained analysis of Samuel R. Delany’s various post-apocalyptic novels. She includes a discussion of the response to Delany’s Nebula-winning The Einstein Intersection (1967). At the 1968 Nebula Awards Banquet, moments after Delany received his prize for Einstein (and where moments later he’d collected another award for “Aye, and Gomorrah”), Blish lambasted the New Wave. Blish complained about the “loosening of the genre’s parameters” and the “re-christening of the genre” as “speculative fiction” (98). I find all of this hilarious as Blish himself wrote fantasy novels like Black Easter (1968) (that would also nab a 1969 Nebula nomination) and far earlier oblique proto-New Wave speculative fictions like “Testament of Andros” (1953). I wonder if Blish aimed such vitriol at a figure like Simak, who took the loosening of the genre’s parameters to extremes during the New Wave–i.e. novels like The Goblin Reservation (1968), Destiny Doll (1971), and Out of Their Minds (1970). Unfortunately, I don’t think it’s surprising that Blish took especial issue with one of the few black SFF authors of the day.

And let me know what pre-1985 science fiction you’ve been reading!

The Photograph (with links to reviews and brief thoughts)

- Elizabeth Baines’ The Birth Machine (1983). One of the least-known SF(ish) volumes of The Women’s Press. From my review: “Pushing against notions that pregnancy is ‘medical: illness,’ the narrative follows a nightmarish tact as an unsuspecting woman is linked up to a nebulously described machine and drugged. Beset by dehumanizing (and often patriarchal) forces, Zelda, without the help of others, comes to terms with her past traumatic experiences that take on the more disturbing elements of fairy tales.”

- James White’s The Watch Below (1966). Despite reading and reviewing this one back in 2011, the claustrophobia and inventiveness still resonates in my memory.

- Jack Vance’s Showboat World (1975). I described this one as a fun adventure. As with so many of his adventure fictions, I remember little in the years after I read them.

- Rick Raphael’s The Thirst Quenchers (1965). Brian Collins over at Science Fiction & Fantasy Remembrance recently reviewed Raphael’s working class slice-of-life story “Code Three” (1963). Despite not finding Raphael’s work that exceptional, I am partial to his charming realism and focus on daily life. I recommend the fix-up Code Three (1967) over the stories in The Thirst Quenchers (1965).

What am I writing about?

It’s a secret! In all seriousness, the stress of the end of the semester (so much grading!) is preventing me from corralling the intellectual strength I need to write reviews. I have numerous planned before the end of the year. I am worried most will be delayed.

In addition to the Simak post mentioned earlier, I reviewed Leigh Kennedy’s “Salamander” (1977), “Whale Song” (1978), “Detailed Silence” (1980), and “Speaking10 to Others2; Speaking3 to Others20” (1981); Lisa Goldstein’s A Mask for the General (1987); and Philip McCutchan’s The Day of the Coastwatch (1968).

What am I reading?

Norman Spinrad. Various themed-anthologies with Gene Wolfe, Le Guin, Lafferty, etc… Various issues of Richard E. Geis’ fanzines in an attempt to identify various reactions to the New Wave.

A Curated List of SF Birthdays from the Last Two Weeks

November 23rd: Wilson Tucker (1914-2006). Huge fan of The Long Loud Silence (1952, rev. 1969) — one of the better nuclear-war themed 50s novels. I must get to more of his work in 2025…

November 24th: Editor T. O’Conor Sloane, Ph.D. (1851-1940). The editor of Amazing between 1929-1938.

November 24th: Spider Robinson (1948-).

November 25th: Amelia Reynolds Long (1904-1978). An earlier female SF pioneer, I’ve only read Long’s “Omega” (1932). Unfortunately, my dislike of 30s SF informs my comments — regardless, she’s a historically important figure.

November 25th: Poul Anderson (1926-2001). One of the authors of the first years of my website. I’ve covered eleven novels and twenty-five of his short stories. I featured “Third Stage” (1962) in my series on “SF short stories that are critical in some capacity of space agencies, astronauts, and the culture which produced them.”

November 26th: Leonard Tushnet (1908-1973).

November 26th: Artist Victoria Poyser (1949-). Yeah, I can’t get behind her aesthetic.

November 27th: L. Sprague de Camp (1907-2000).

November 27th: C. C. MacApp (1917-1971)

November 27th: Dave Wallis (1917-1990). I thoroughly enjoyed his sole SF novel Only Lovers Left Alive (1964).

Kirby’s cover for the 1958 UK edition of Asimov’s The Caves of Steel (1958)

November 27th: Artist Josh Kirby (1928-2001). Perhaps best known for his Discworld covers, Kirby was a prolific contributor of art for a vast variety of authors.

November 28th: Richard R. Smith (1930-). A prolific contributor to the magazines in the 1950s, I’ve yet to read his work.

November 28th: Artist Walter Velez (1939-2018).

November 28th: Editor and author Donald J. Pfeil (1937-1989). Best known for editing Vertex (1973-1975).

November 29th: C. S. Lewis (1898-1963).

November 29th: Madeleine L’Engle (1918-2007).

November 29th: Kevin O’Donnell, Jr. (1950-2012).

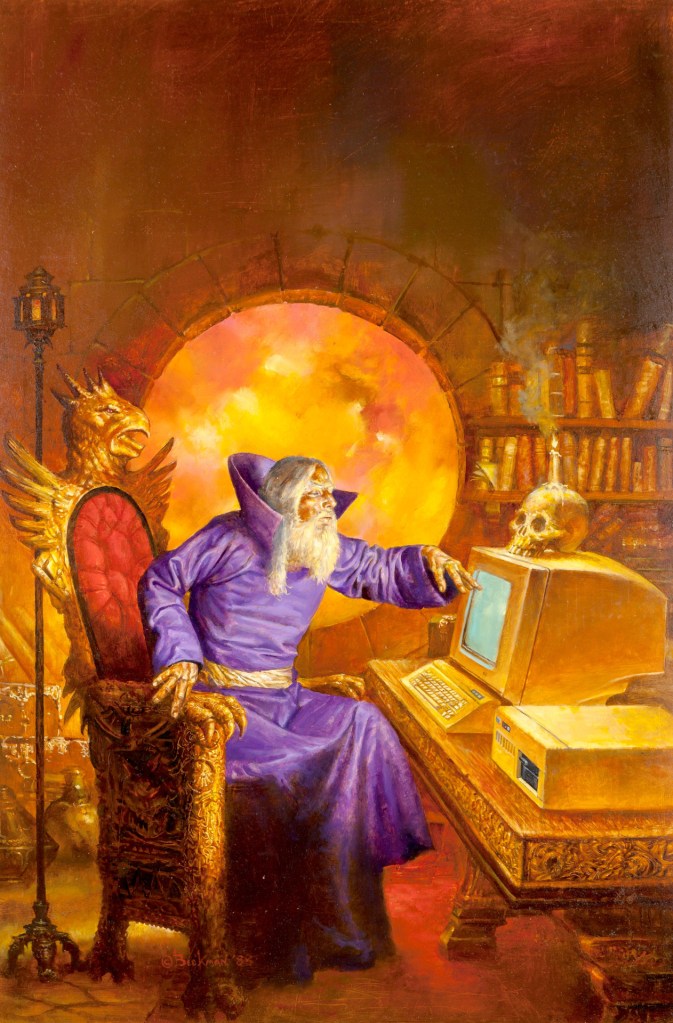

Doug Beekman’s cover art for Barbara Hambly’s omnibus Darkmage (1988)

November 29th: Artist Doug Beekman (1952-).

November 30th: Artist Gino D’Achille (1935-2017). Best known for his various Edgar Rice Burroughs covers.

December 1st: Charles G. Finney (1905-1984). I’ve been meaning to read The Unholy City (1937)….

December 1st: John Crowley (1942-. I’ve reviewed Beasts (1976) and The Deep (1975).

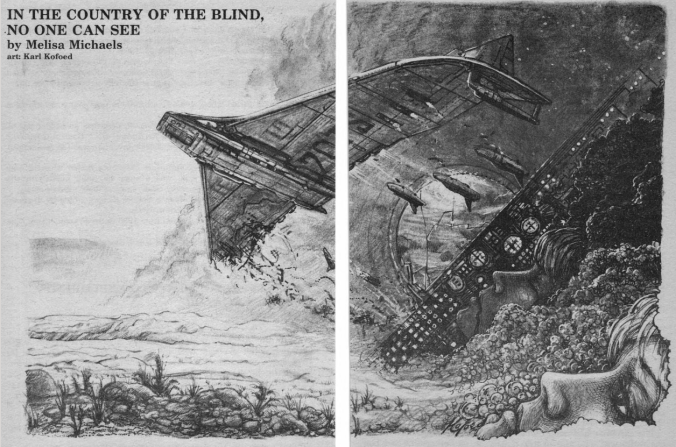

Karl Kofoed’s interior art illustrating Melisa Michaels’ “In the Country of Blind, No One Can See” in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (January 1979)

December 1st: Artist Karl Kofoed (1942-).

December 4th: Author Ian Wallace (1912-1998). In the earliest days of my site I reviewed Croyd (1967) and found it lacking. I have not, for good or bad, returned to his work since.

December 5th: John A. Williams (1925-2015). One of only a handful of black speculative fiction authors in the 60s and 70s, I’ve previous tackled Captain Blackman (1972): “a fever dream of an injured black Vietnam War soldier hurled via hallucinatory time-travel into all of America’s conflicts.”

December 6th: Roger Dee (1914-2004).

December 7th: Leigh Brackett (1915-1978). If you haven’t read The Long Tomorrow (1955), along with the Tucker mentioned above, one of the better nuclear-war themed 50s novels.

December 7th: Julia Verlanger (1929-1985). One of a handful of female French SF authors from the decades I cover. Unfortunately, other than one short story “The Bubbles” (1956, trans. 1977) none of it is translated into English.

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX

Been picking my way through the Science Fiction Hall of Fame Vol. 1, which includes Surface Tension by Blish, a story I enjoy for its inventiveness and I hate to say it world building. Also reading vol. 2 of PKD’s Selected Stories. The standout for me has been The Days of Perky Pat. And I just finished I Am Legend And Other Stories. I felt that I Am Legend was more satisfying than the short fiction used to pad out the volume. Finally, I have my nose in two famous novels I somehow haven’t read: Dune and Flowers for Algernon.

Currently working on a Substack post about The Roads Must Roll.

I reviewed “Surface Tension” in the first year or so of my site. I enjoyed it then — not sure what I’d think now. As for Blish, I highly recommend “Testament of Andros” (1953) which I mentioned in the post. My review: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2022/12/22/book-review-so-close-to-home-james-blish-1961/

I read those PKD’s volumes as an older teen (pre-site). I also remember enjoying “The Days of Perky Pat.” I can’t say my most recent PKD review was as interesting, although I selected it entirely for the topic: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2024/10/13/short-story-reviews-phillip-k-dicks-stand-by-variant-title-top-stand-by-job-1963-milton-lessers-do-it-yourself-1957-and-h-beam-piper-and-john-j-mcguires-hunter-patrol/

I read Flowers in high school (I’m not sure if it was the novella or novel version). I also read Dune around then and became obsessed with all the sequels and prequels written, ineptly, by his son. I have not returned to Dune since.

“Surface Tension” is so great. I’m not sure what else Blish has done that was of a similar caliber.

I’m relying on reading memories from my late teens but I seriously enjoyed A Case of Conscience. And the “Testament of Andros” (1953) story I mentioned earlier in my post.

I read A Case of Conscience earlier this year and thought it was stimulating.

I only remember my response to the novel as it was half my life ago (late teens). On the list of things I should reread if I were much of a rereader!

JB: I find all of this hilarious as Blish himself wrote fantasy novels like Black Easter (1968) (that would also nab a 1969 Nebula nomination) and far earlier oblique proto-New Wave speculative fictions like “Testament of Andros” (1953).

In Blish’s possible defense, I suspect what he wanted was intellectual rigor and what he was against was the slop of ‘anything goes-a wizard did it’ fantasy. I’m pretty certain, for instance, that when he wrote Black Easter and The Day After Judgment, he probably thought he was setting an example by showing what fantasy should be like, damn it, if the bloody authors would only do their homework like he did. That’s certainly what those books read like, IIRC these many years later — Blish’s research into medieval theology, demonology, John Milton, and such were prominently on display.

More generally, Blish was a peculiar author. His intellectual rigor could on the one hand be anal-retentive and often outright deadening in the emotional affect of his writing. On the other hand, it would sometimes lead him to follow a premise far, far beyond where almost any other author would leave it. A couple of instances: Blish posits antigravity and follows it all the way to cities like Manhattan and Scranton, Ohio, and Chicago taking off and traveling around the universe as ‘bindlestiffs’ in the Cities In Flight series; or in The Day After Judgment, a section which describes with some specificity how, after all the demons are released from Hell in the previous book, the Pentagon high command and NORAD throw all their weapons systems, thermonuclear and otherwise, at the hordes of Hell.

And I’ll quote from Wikipedia’s description of Judgment‘s finish: “In a lengthy Miltonian speech at the end of the novel, Satan Mekratrig explains that, compared to humans, demons are good, and that if perhaps God has withdrawn Himself, then Satan beyond all others was qualified to take His place and ….would be a more just god.”

So, a book about demonology and black magic treating those subjects seriously, so in that sense is a fantasy. Yet a fantasy that offers none of the usual satisfactions that fantasy gives its readers, and descends into Miltonian verse to discuss theology for its final section. Interesting to discuss now, though in my memory dry as hell to the point of being outright boring when I read it as a young teenager.

Beyond ‘Surface Tension,’ two Blish short stories are arguably significant to the genre’s development, ‘Common Time’ and ‘A Work of Art,’ both of which you covered in your review of Blish’s collection, Galactic Cluster, and rated strongly. Except where you found the ‘first contact’ part of ‘Common Time,’ to be “a rather timid/silly introduction of aliens into a fascinating example of early hard science fiction,” many think that’s the most significant and adventurous part of the story as Blish attempts to depict the aliens are beings unbound by time — angels, essentially.

I’ve enjoyed my explorations of Blish’s fictions. I’ve read two in that Cities in Flight sequence as well. I can’t say I remember much from the Galactic Cluster collection, one of the earliest reviews on my site that I probably wrote even earlier but had posted on Amazon first. But yes, from his takes on fantasy it sounds like he should respect authors that take risks, as he did.

I don’t know if you saw it or not, but here’s my review of I Am Legend (1954): https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2022/07/06/book-review-i-am-legend-richard-matheson-1954/

I’ve also covered two very satisfying Matheson short fictions relatively recently that are not in that collection you mentioned: “Pattern for Survival” (1955) and “Through Channels” (1951)

Moving on from my recent H.G. Wells bender, I’ve been going through several of the entries in Joshua Glenn’s “The Radium Age” book series, and two in particular were shockingly good – E.V. Odle’s “The Clockwork Man” and J.D. Beresford’s “World of Women”. Just in an early 20th century mood, I guess. Part of the appeal is certainly historical, tracing how far back various ideas around feminism, utopia/dystopia, and technology go, and how they are still echoing in our own era. The Beresford, for example, traces the total breakdown of British society following a pandemic that wipes out the majority of males. The ensuing struggle to constitute a new society from the ruins reminded me of much later works like “Greybeard” (or one of the numerous other post-nuclear books you’ve reviewed). And then of course the earlier sections describing how the pandemic unfolds were eerily familiar for obvious reasons.

Those both sound interesting (despite my general frustration reading pre-WWII SF). I am certainly willing to read scholarship about them!

As for Greybeard, I think I should give it a reread. I finished it a few years ago but was never able to put together a review.

Speaking of Gene Wolfe, I’m starting my first of his with Soldiers of the Mist.

I have yet to tackle one of his novels. I have covered quite a few of his short fictions — which are always thought provoking. “Silhouette” (1975) is a particular favorite of mine: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2017/01/22/book-review-the-new-atlantis-and-other-novellas-of-science-fiction-ed-robert-silverberg-1975-le-guin-wolfe-tiptree-jr/

That one is a bit of a challenge. I liked it a lot, but even as someone who very much enjoys the “unreliable narrator” device, it sometimes felt like work to keep track of all the mythological allusions and dropped clues that are key to the narrative. To be fair I’ve found this is true of a lot of Wolfe’s work: it’s very rewarding if you put in the effort and really pay attention. If you dont it can kind of fly by you and just be a but puzzling. For my part my entry point was The Fifth Head of Cerberus and then the Book of the New Sun tetralogy, both of which I recommend highly.

No doubt on the additional effort.

This was recommended to me when mentioned on Bluesky, including picking up Herodotus: https://bsky.app/profile/rereadingwolfe.bsky.social/post/3lbxvr7phnk2v

Not saying that I wouldn’t put in such effort. I did read The Iliad in an attempt to appreciate Dan Simmons Ilium better.

@jgardner3 I remember reading the Illium books a few years after they came out (my late teens). The early 2000s were the last time I regularly read contemporary SF.

I will eventually get to his longer works. Unfortunately, just spent 10 hours grading papers this weekend… At this point in my life, it’s probably better to tackle a few Wolfe short stories. Hah.

Glenn’s series is designed specifically to highlight authors that generally predate the Gernsback/pulp period – most of what I’ve read so far occupies a strange liminal territory between the big guns of the preceding era (Wells, Verne etc.) but prior to the codification of a lot of the genre tropes that would come to predominate in the pulp era. And there’s a lot of anxiety and prognostication about war, technology, the direction of society, “progress”.

Sounds like a great series filling an important void. I am far less interested in history (through SF) pre-WWII but… these things shift and change… maybe in the future!

Keep on sharing the exemplars you find. I love learning about them.

I’m very excited to come across your blog via a link to your Simak post. My dad was always a big fan of Simak and I’ve really enjoyed what I’ve read of him (mostly City and assorted short stories, though I’ve just discovered my library has all 14 volumes of his Complete Short Fiction as ebooks).

I’m currently working through a personal project to read all the Analogs that my dad gave me before he died in 2020, basically a complete run from June 1970 to March 1981, which coincided exactly with the period in my dad’s life between graduating college and the birth of my older sister. I’ve read 8 issues so far, and I have to say, I can’t wait to get past the Campbell era (just 11 more issues till I get to Bova). I think if I had been alive back then, I would’ve gone with one of the other magazines at the time, but I’ve been trying to appreciate the historical context of how my dad would’ve come across Analog and his interests at the time. While I don’t care for Campbell, I have been enjoying the reviews from P. Schuyler Miller and seeing what actually succeeded in becoming big hits or not (there’s a fun bit where he mentions in an aside coming across Stanislaw Lem in an issue of SF Commentary, written before Solaris is released, so he’s like “Yeah, some random Polish guy had an interesting article I guess”).

I’ve got a copy of James White’s The Watch Below but haven’t read it yet (I picked it and All Judgement Fled up at a convention a few years ago because I loved his Sector General stories so much).

Thanks for stopping by. I hope you enjoyed my Simak article. Are you referencing my post on six of his interviews? Worldcon speech? Or my much more intensive article on his accounts of organized labor?

That sounds like a wonderful project to honor your father. And read some interesting (despite Campbell) SF magazines and historical context along the way. I, too, would be desperate for the Bova issues to come around considering my general ambivalence (verging on frustration) with PSI powers, narratives of men who prove that man is best, and SF that fixates on the science.

I thoroughly enjoyed All Judgement Fled (there’s a short/old review on my site). If you haven’t read White other than his Sector General stories, you might be in for a little bit of a surprise. They’re far more gritty, depressing, and brutal.

Whoops, I meant to refer to your Simak’s Worldcon speech post (when it was linked on File 770), but I’ll definitely go back to find the other two you mentioned!

I definitely agree with all your points about the era, though I do have a soft spot for some psi like with James H. Schmitz’s Telzey stories (so far!). I liked the peaceful resolution in “Compulsion” (another factor I always appreciated in White’s more pacifist Sector General). The only other White I’ve read was his collection *The Aliens Among Us*, but I read that over 10 years ago, so I only remember the two “abduction/invasion but actually planet evacuation” stories.

No worries. I thought you might have come from File 770 — all three were linked over the last few months 🙂

My article “We Must Start Over Again and Find Some Other Way of Life”: The Role of Organized Labor in the 1940s and ’50s Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak was my main project this year. https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2024/09/13/exploration-log-5-we-must-start-over-again-and-find-some-other-way-of-life-the-role-of-organized-labor-in-the-1940s-and-50s-science-fiction-of-clifford-d-simak/

“re-christening of the genre” as “speculative fiction” – a term advocated for by that New Waver Robert A. Heinlein

I remember enjoying Raphael’s Thirst Quenchers and Code Three.

Yeah, none of Blish’s reactionary complaints make much sense… Which is why I found the Simak’s speech so refreshing. He simply is not bitter that there are new voices. And more than that, he too will try to shift and change his own views on the nature of genre over the course of the 70s.

And Simak was almost two decades older than the prematurely curmudgeonly Blish

Del Rey’s intro to his first Best SF annual suggested to me a possibility I had overlooked, that the Old Guard hostility to New Wave was in part because they thought SF’s market size was fixed and if the New Wave sold more, that meant the Old Guard had to sell less.

Blish’s 1961 Stardwellers had this rant about rock and or roll music:

“Of course, music for dancing has to be different from concert music in kind. But in those days it was vastly inferior in quality, too; in fact most of it was vile. And it was vile mainly because it was aimed at corrupting youngsters, and then after that job had been done, the corrupted tastes were allowed to govern public taste in music as a whole. We’re very lucky that we ever got off that particular chute-the-chutes. It would never have unwound itself if it hadn’t been for the revolution in education, which among other things involved the realization that music — and poetry — are primarily arts for adults, and for exceptional adults at that.”

He wrote that when he was 40. I wonder what he would have like if he’d lived to seventy?

My latest old time book was a Philip Wylie, that was two parts soap opera to one part atomic war. Turns out a-bombs simplify romantic triangles quite efficiently.

In Asimov’s intro to Blish’s A Work of Art (in a retrospective Years Best anthology) Asimov notes Blish’s poor opinion of the Beatles.

Are you reading Tomorrow! ? I read the Readers Digest Condensed version of that in the 1970s (Twin cities make great locations for an impromptu case study on civil defense)

I am! It’s not very good and does not make the point Wylie thinks it does, but it’s not without some interesting aspects. For example, local matriarch Minerva Sloan’s efforts to disentangle herself from the Infirmary, a hospital for African Americans set up by her late husband, are continually frustrated by the fact Alice Groves, the highly credentialed black woman who runs the Infirmary, is ever so slightly enormously smarter than the matriarch and is usually five or six moves ahead. Minerva’s no slacker, either: except for the matter of the Infirmary, she usually gets her way. Impressively, her fortune seems to come through WWIII surprisingly intact.

Speaking of the Wylie, Tomorrow! is extensively discussed in Jacqueline Foertsch’s Reckoning Day: Race, Place, and the Atom Bomb in Postwar America (2013) that I mentioned earlier in the post. She’s of course charting any author that tackles race and nuclear war (she pulls in TONS of great articles from contemporary newspapers and other fiction stories by black authors). Great stuff!

Re Blish and Delany: In his collection of reviews and essays MORE ISSUES AT HAND (Advent 1970), Blish says in a chapter titled “Making Waves,” in connection with Delany and Zelazny:

“Of the two, I find Delany harder to read, because his imagery is so constantly to the fore, and so consistently foggy, that I often suspect that he himself does not know what he means by it–and his explanations (in the fan press and on the academic lecture platform) seem to fog the matter still further. Here I am very much out of step. His novel Babel 17 [sic] won a Nebula as the best of 1966, but I thought it pretty close to being the worst, and when his The Einstein Intersection won the same award in 1968, I stepped quietly out into the kitchen and bit my cat. That Delany has drive, insight, and a certain music I cannot doubt, but neither his clotted style nor his zigzag way of organizing a story strike me as being much better than self-indulgent and misdirected. If I am right about this–and my experience with Ellison suggests that I am more than likely to be wrong about it–Delany’s early popularity, laid on well before he was either in control or was convinced of the necessity of being in control of his manner or his matter, may well turn out to be destructive. He would not be the first writer whom immoderate early praise (though every writer longs for it) put out of business, at least for a damagingly long period; see my remarks on Sturgeon.”

In a footnote, he describes Delany as “a merry and handsome young Negro who travels in hippie dress and has educated himself as a composer as well as a writer.”

Delany does not appear in the index of Blish’s later collection The Tale That Wags the God (Advent 1970).

Re Blish and Simak: he says nothing about Simak’s work in either of the two ISSUE AT HAND books or the later one.

Blish’s New Wave opinions are obviously a bit reactionary and sexist/racist to varying degrees but honestly I agree with his appraisal of Delany here. Having slogged through Babel-17, Nova, part of Dhlagren, and a smattering of short fiction, I have hard time getting past the overall weakness of the prose despite the obvious groundbreaking nature of the premises and point of view. I find myself wishing the guy was just a better stylist/writer.

Thanks for the quote from Blish. I need to read his criticism more systematically. And both Babel-17 and The Einstein Intersection are great…. haha. Oh Blish. I am not surprised that he doesn’t talk about Simak. I think it would weaken anything he wants to say about 60s/early 70s generic boundaries. And I can’t help but think some of his criticism is more connected to views of the new generation of authors… which, again, is a bit humorous considering his later 70s relationship with genre-bending author (and member of the New Wave) supreme, Josephine Saxton.

I’ve been reading Silverberg’s Book of the Skulls and I’m struggling to consider it science fiction.

Hello Neil,

Sorry for my delayed response — grading and stress of the end of the semester prevents me from having much time to do anything. I am eager to read that Silverberg. It’s one of the few I’m missing from his glory period. But yes, I’ve heard similar arguments about its generic identity. Enjoying it regardless?

Yes I enjoyed it. It’s an interesting study into humanity.

I’ve been on a Zelazny binge lately. Creatures Of Light And Darkness, then Doorways In The Sand, and currently Lord Of Light.

Hello, It seems that your periodically have Zelazny binges! I’m assuming he’s one of the authors you love rereading? (I remember you saying he’s one of your favorites). I need to buckle down and knock out some of the big-hitting New Wave novels that I haven’t read yet — I have Creatures of Light and Darkness and stuff like Spinrad’s Bug Jack Barron on that mental list.

Zelazny is my go-to writer for when I am feeling depressed or overwhelmed. There is a relentless hopefulness in his books–his characters (who are similar enough that I think of them as the same character, just reskinned for different books) face all sorts of world-ending cataclysms with poise and humor and a kind of cheerful cynicism that makes my own troubles seem small.

Many thanks for this feature and all this discussion and history. I very much enjoy it all.

I’ve been reading an anthology which is REALLY pre-1985: Voices from the Radium Age, edited by Joshua Glenn, MIT Press, 2022. Mr. Glenn is a strong admirer of SF from what he calls the “radium age,” before John W. Campbell’s Golden Age.

Here is the blurb and contents from the publisher’s website:

“This collection of science fiction stories from the early twentieth century features work by the famous (Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes), the no-longer famous (‘weird fiction’ pioneer William Hope Hodgson), and the should-be-more famous (Bengali feminist Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain). It offers stories by writers known for concerns other than science fiction (W. E. B. Du Bois, author of The Souls of Black Folk) and by writers known only for pulp science fiction (the prolific Neil R. Jones). These stories represent what volume and series editor Joshua Glenn has dubbed ‘the Radium Age’—the period when science fiction as we know it emerged as a genre. The collection shows that nascent science fiction from this era was prescient, provocative, and well written.

“Readers will discover, among other delights, a feminist utopia predating Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland by a decade in Hossain’s story ‘Sultana’s Dream’; a world in which the human population has retreated underground, in E. M. Forster’s ‘The Machine Stops’; an early entry in the Afrofuturist subgenre in Du Bois’s last-man-on-Earth tale ‘The Comet’; and the first appearance of Jones’s cryopreserved Professor Jameson, who despairs at Earth’s wreckage but perseveres—in a metal body—to appear in thirty-odd more stories.

Contents

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, “Sultana’s Dream” (1905)

William Hope Hodgson, “The Voice in the Night” (1907)

E. M. Forster, “The Machine Stops” (1909)

Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Horror of the Heights” (1913)

Jack London, “The Red One” (1918)

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Comet” (1920)

Neil R. Jones, “The Jameson Satellite” (1931)

Glad to see others picking up on this series. I read this anthology recently as well (ok, I skipped the Jack London entry) and moved on to some of the novels in the series as noted upthread. Glenn’s definitely doing some valuable work with this imprint.

Yes, I found it in the Vancouver Public Library. Apparently Glenn has done a follow-up anthology. He seems to be a scholar and popularizer of Radium Age SF.

Let me know if any of the volumes are particularly interesting! While I probably, at least at this moment, do not plan on reading them, I am always excited when new anthologies of older SF appear — and especially of an era that is normally glossed over.

Joshua Glenn’s anthologies are published by MIT Press, which has published several works from the “radium SF” era. There are several other anthologies of vintage SF, if you will, including Scientific Romance: An International Anthology of Pioneering Science Fiction, edited by Brian Stableford and published by Dover Books in 2017. (I gather “scientific romance” is usually considered a precursor to U.S-style genre fiction.)

To further place the James Blish comments in perspective, there is an essay by Blish titled “Credo” included as an introductory piece to the Aldiss/Harrison edited Best SF: 1967 (their first). In that essay, he lambasts the Judith Merrill edited Year’s Best SF series for including things he feels should not be considered as “science fiction”, laying out his own ground rules as to what he considers proper science fiction. He concludes by saying he trusts Harrison and Aldiss to perform a better job than Merrill.

In what I can only consider to be Aldiss and Harrison getting a laugh on Blish after including his reactionary essay to open their anthology series, the two editors go on to republish a James Thurber story, and Ballard’s “The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race”. Rightfully so in the case of Ballard, as it was definitely a highlight of the year for “speculative fiction”, but both stories are examples of things that Blish explicitly did not want to see in the “year’s best” retrospectives.

Also, I believe a strong argument could easily be made that the Aldiss/Harrison version would go beyond Merrill’s as far as publishing experimental works of fiction.

Hello Chris, I should read more of his criticism — I’m pretty sure I acquired a collection of his essays in the last year.

I just finished the H.G. Wells collection In the Country of the Blind and Other Selected Stories. Not all of them were SF; some were horror stories and some didn’t contain any speculative or fantastic element at all. A bit hit and miss overall, but I did enjoy a lot of them.

Other than his best known works like The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, I haven’t read a ton of Wells.

I haven’t read much Wells outside of the four classics either, and from what I hear about him elsewhere, I more and more get the impression that they’re sort of an anomaly – all written within a few years and immensely influential on SF history, but not much of the rest of his long career is remebered in the SF-world.

The short stories often have good ideas, but also some that are sort of silly, and he doesn’t use them in a way that makes them groundbreaking like The War of the Worlds etc. were. The best ones have an intriguing philosophical angle that perhaps influenced Borges, who was a big fan.

Of the classics, I still think WotW is amazing, but The Island of Doctor Moreau, which I only read recently is definitely also up there. Easily one of the scariest books I’ve ever read.

I am definitely a huge fan of Borges — I have read all his collected fiction, albeit, it fits in a single large volume.

Yes, I really like Borges as well, I’m actually reading the Labyrinths collection right now (half of which I’ve read elsewhere, but a long time ago). It wasn’t a deliberate plan to read him after Wells, I wasn’t aware of his admiration until it was mentioned in the preface, but now I can definitely see some proto-Borges elements in Wells-stories like “The Door in the Wall”, “In the Country of the Blind” or “The Crystal Egg” (which must certainly have inspired “The Aleph”).

A Wreath of Stars by Bob Shaw.

I’m not quite sure whih impulse led me to read three of Shaw’s novels this year, but this one was probably the best. Shaw clearly had a sense of humour and this shines through, and the central idea driving the novel itself is a gripping and weirdly plausible one. The characterisation is a tad dated (though not as dated as the Silverberg mentioned above). I had enough engagement with this to make a pretty satisfying read.

I fancy Ballard’s Hello America next, though that may have to wait until 2025.

I felt the same in 2021 when I impulsively decided to read a bunch of Garry Kilworth novels — I completed reviews of In Solitary (1977) and The Night of Kadar (1978). Part of the fun is exploration!

I am eager to know your thoughts on Hello America. It’s currently staring at me from the shelf.

Your less-than enthusiastic comments on Goldstein’s General reminded me I’d had a copy of Tourists sitting on a rear course in the TBR bookcase, so I pulled it out … I was entertained. A magic-realism effort set in an imaginary third-world country. (Like an Islamic country, but without Islam. Central Asia? MENA? Elsewhere in Africa? As vividly described but as ambiguous as Morris’s Hav.) If it were published today I expect it would be marketed as YA, given its plucky 14-year-old female protagonist; but then, if it were published today it probably would would be cancelled by the Goodreads YA tribes and withdrawn.

Currently finishing up Marjorie Worthington’s memoir of Willie Seabrook, but next up: C.L. Moore’s Northwest of Earth (an apparently-complete collection of the series published by Planet Stories (the press, not the magazine 😉 ).

In my non-SF reading, I am a huge fan of magical realism. I know it’s probably a bit predictable but I owe a lot to my 9th grade teacher who had us read and create journal entries on Gabriel García Márquez’s “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.”

For once I’ve been reading old stuff! 😉

I’ve recently finished an Ace Double from 1965, with Fred Saberhagen‘s The Water of Thought and John Rackham‘s We, the Venusians

This is Saberhagen’s 2nd novel, after The Golden People, which I first read decades ago, but haven’t reread for almost as long!

Boris Brazil, a Planeteer, lends a hand when one of the colonists on the planet he’s visiting apparently overdoses on the titular and previously unknown Water of Thought, attacks some natives and flees upcountry towards where a researcher disappeared a year earlier.

The search party turns out to consist partly of prospective smugglers, wanting to find supplies of the native drug. The researcher persuades them all to participate in a native initiation ceremony, which has major consequences…

Some interesting ideas crammed into quite a short book (113 pages) although sometimes the meaning needed teased out a little.

I’ve read several of the other author’s books under his nom de plume of John T. Phillifent but none as by John Rackham.

Venus has been colonised and its jungles are the source of a wonder drug which people will pay a fortune for. The colonists have coerced the green, human-like but apparently almost mindless native ‘Greenies’ to tend the plants for them.

On Earth the world’s entertainment and culture is extremely degraded with banal, repetitive musak filling everybody’s time.

A rare individual, though, scrapes a living playing virtuoso piano in a tiny nightclub. He’s blackmailed into agreeing to perform on Venus but the snag is that he is actually a ‘greenie’ with a dyed skin passing as an Earth human!

This is a key element and I’m afraid it just doesn’t work nowadays (he uses ‘anti-tan’ which turns his skin white but it was originally developed to turn black skin white and so wipe out racism!) Passing over that aspect, he goes to Venus but joins the natives and leads them to a glorious victory and re-negotiation of the terms of their labour growing the drug!

As Ace Doubles go, this pair of novels shared some themes and the action in both raced along slightly confusingly but enjoyably! They each had a human colony on a planet difficult to map or explore, natives of dubious or unknown intelligence, a rare drug the natives rely on and can’t afford to lose control of to the humans…

Despite the problems with the Rackham novel, it sounds like it fits the theme of workers rights. Do they explicitly create a union? Or something with the trappings of a union? Or is more an armed rebellion?

No Union equired, I’m afraid. There are clan leaders but the entire population of Greenies (except the mentally deficient ones near the three human colonies) are telepathetically linked together. The clan chiefs/wise men can steer the concensus but our hero ends up convincing them to follow him and he can just think what he wants done and off they go to do it! (They severely damage the giant plastic dome over the main settlement and force negotiations)

He settles down with his new Greenie mate and thinks of himself as ‘King of the Greenies’. Reminded me a bit of the bitter protagonist in his later Phillifent title, ‘King of Argent’ where an enhanced human (and his bride) stays on a rich mining planet and fights off the evil mining corporation that sent him there!

The skin dye aspect reminds me of the troubling and profoundly hateful Taine of San Francisco novel The Menace by David H. Keller. In the first part of the novel, Black mad scientists use a similar technology or process to the one you describe to become white for the purpose of dominating the economy with gold (IIRC distilled from seawater) and using their new position to turn all Black people in America white. It’s one of those every-accusation-is-a-confession where the Blacks in the story have the mirror image worldview of a white racist. Keller clearly viewed Blacks as a sort of fifth column. (He apparently had a similar view of women. See The Feminine Metamorphosis which is almost the same story but with a gender swap rather than a race swap element.)

My hypothesis is that identity swapping could actually be a fruitful theme in science fiction in more sensitive hands and at least an interesting one in blunt hands. For the life of me, I wish I could remember the plot of James Weldon Johnson’s (non-SF) novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. I remember thinking it was a really solid book when I read it 20 years ago. I think I have a copy of the Ace Double you describe kicking around if I didn’t sell it recently. I’m much more likely to read it now.

Well, I’m not exactly recommending either of the halves of the Ace Double! Neither of them are particularly good but the Saberhagen is an early work by an author who went on to write better stuff and had a long career – Rackham/Phillifent carried on for a while but never really got beyond his pulp roots writing Ace Doubles.

The roots of ‘anti-tan’ are skimmed over; he really just wants his greenie to be able to pass himself off as being from Earth. The reason it was invented is covered in only a sentence or two and I don’t think he gave the implications much thought at all. But he does make quite a bit of the hero running out of it on Venus and being desperate not to be seen as his skin slowly reverts to being green. He’d have happily kept taking it, finished his gig and gone back to Earth if he could have.

Another version of the same theme that I acquired a few months ago but haven’t featured in my purchase posts — Harry Roskolenko’s Black is a Man (1953). Apparently it’s a more Kafka-esque angle to the SF-ish skin color changes as a way to attempt to say something (often in a racist manner) about the illogic of racism. We shall see!

I just started “334” by Thomas Disch and the first chapter was amazing.

On my shortlist of things I really need to get to!

I finished it and it’s fantastic. I think it’d be right up your alley.

I know it will be right up my alley! It’s the issue of time, whim, and current projects…

I just read Anthony Trollope’s The Fixed Period (1882). There’s precious little SF more “pre” 1985 than that! 🙂

Other than your review, I can’t say I know anything about that one! As always, I enjoy when you cover older esoterica (or maybe they’re just esoterica to me — haha).