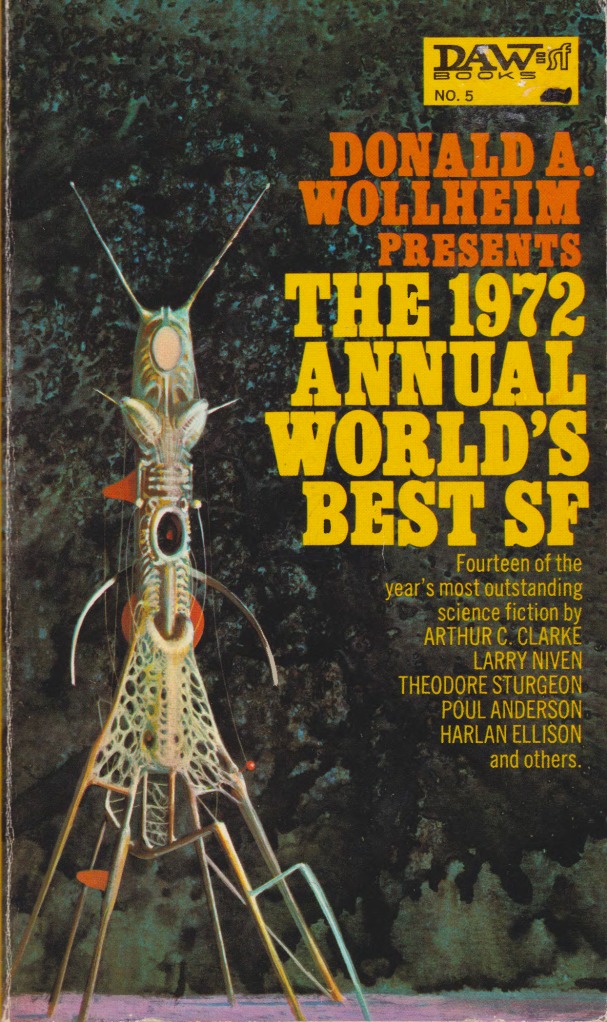

(John Schoenherr’s cover for the 1972 edition)

3.5/5 (collated rating: Good)

The 1972 Annual World’s Best SF, ed. Donald A. Wollheim (1972) doesn’t feel like a “best of” collection. The majority of the contents are unspectacular space operas and hard SF in the Analog vein. Amongst the chaff, a few more inventive visions shined through—in particular, Joanna Russ’ mysteriously gauzy and stylized experiment replete with twins and dream machines; Michael G. Coney’s evocative overpopulation story about tourist robots; Christopher Priest’s “factual” recounting of human experimental subjects that isn’t factual at all; and Barry Malzberg’s brief almost flash piece about differing perspectives all tied together by the New York metro.

On the whole, I give it a solid recommendation although the best can be found in single-author collections.

Brief Analysis/Summary

“The Fourth Profession” (1971), novelette by Larry Niven, 3/5 (Average): Nominated for the 1972 Hugo Award for best novella. In a series of flashbacks to a fateful night, our bartender narrators recalls the arrival of a Monk (an extra-terrestrial draped in a robe) and various drug-induced effects of the pills the alien dispensed. The secret service interviews the bartender and his female assistant for all the information (“memories”) imparted by the pills—spaceships, fusion reactors, languages…. As the memories slowly come back, the “true” intention of the alien merchant becomes clear.

The first third held my attention… However, due to the setup, large sections of latter two thirds recount ad nauseam “memories” imparted by the drug including lengthy exposition on the science behind solar sail ships. But, it’s Niven! Tons of technical details are required and expected! That said, Niven’s adept at pacing the story’s reveal. Ultimately the story falls into the “why on earth did this receive a Hugo nomination” camp not because it’s atrocious but because it’s only functional. At one point I devoured Niven’s technologically savvy visions–“The Coldest Place” (1964), Ringworld (1970), Ringworld Engineers (1979), The Integral Trees (1984), etc. My current opinion of Niven is a good indicator of my evolving views on SF in general.

For a more positive and detailed take on the story consult MPorcius’ review

“Gleepsite” (1971), short story by Joanna Russ, 4.5/5 (Very Good): A calculated and fascinating exercise (in the best way) in implication, suggestion, and dangling oblique hints… The hints: A world of poisonous air, a narrator who works for a “travel agency whose hints of imaginary faraway places (Honolulu, Hawaii–they don’t exist) […] exacerbate the longings of even the most passive” (60), and a population of almost entirely women… The plot? The narrator sells a dream device that conjures the “imaginary faraway places” to two “fiftyish identical twins” (60) before disappears into a “screaming wind” as a “little bat-man-woman with sketchy turned-out legs and grasping toes” (64). The twins decide that they too will “tinker a bit” (65) with the dream object. Is this but a beginning of a cycle? Imaginative lure and sinful desire?

The story is filled with memorable imagery and odd scenes… Beautiful if distant. Recommended.

For a more detailed (and equally positive) take on the story consult MPorcius’ review

“The Bear with the Knot on his Tail” (1971), novelette by Stephen Tall, 3/5 (Average): Nominated for the 1972 Hugo Award for best Short Story. “The Bear with the Knot on his Tail” is one of multiple stories in a sequence charting the voyages of the exploration ship Stardust. In the vein of Star Trek (but without the intriguing characters), the episodic stories follow the crew on first contact missions. This particular “episode” finds the crew drawn to the source of strange alien music. Though the hunch of the ship’s resident artist who “draws” the source of the music (what? yeah, don’t think about it too much), the Stardust sets off to a planet in Ursa Major. And the music? The mournful “we are going to die in just a few hours due to a nova” noises of egg-like aliens…. And of course, the crew will be able to save the day! Or rather, start the alien culture anew. It’s bland. It’s a tad silly.

Tell me why this was nominated for the Hugo?

“The Sharks of Pentreath” (1971), short story by Michael G. Coney, 4.5/5 (Very Good): One of the best stories in the collection….

Overpopulation! I adore speculations of societal transformation due to too many people, a lack of resources, urbanization, etc. Pentreath, a small English seaside resort town (think Broadchurch but without the murder if you’re an American), contains the normal knickknack stands and petty rivalries. In this overpopulated future, people live in rotations: a few years in a steel box hooked up to some tubes and a year in the flesh. While in the steel box you can still explore the world via a weird-looking robot called a “remoter”… Pentreath is filled with “remoters.” Our main characters run a store in Pentreath and encounter an elderly “remoter” couple. For once I won’t spoil the tender ending, but it almost made me tear-up a bit.

Coney’s SF contains a delicate emotional tenor—nostalgia, longing, and love—seldom achieved by his contemporaries. Check out my review of Friends Come in Boxes (1973) and Hello Summer, Goodbye (variant title: Rax) (1975) if you haven’t already.

“A Little Knowledge” (1971), novelette by Poul Anderson, 3/5 (Average): A solid space opera where the humans are evil and the aliens are good and only naïve on the surface. A group of humans steal an alien spaceship. The alien is bewildered: what profit could a technologically primitive spaceship bring to the criminals? But the alien has a plan, involving a big dollop of hard science and knowledge of his environs, to trick the human criminals. “A Little Knowledge” is part of the Psychotechnic League series of stories. Recommended for fans of Anderson.

“Real-Time World” (1971), novelette by Christopher Priest, 4.5/5 (Very Good): Reviewed originally here.

“Real-Time World” evokes a beaker containing all Christopher Priest’s favorite ideas…. But, without any other context to anchor the realty of the experience, only the beautiful chemical reactions swirls of the story can be grasped. The narrator, whom we initially equate a scientific exactitude to his observations, comments on the inhabitants of an “observatory” whom he considers insane: “In cold factual language: I’m a sane man in an insane society” (134). No one seems to know the purpose of the observatory, where it is, or if it is even possible to leave. The “cold factual language” obfuscates a complete lack of firm knowledge. He believes that the inhabitants, due to a minute temporal displacement, are able to foretell events of the future. But, as these current events from the real world are sent to him and only him, they might be entirely fabricated. The reader is left grasping at any shred of “reality.”

Experimental stories like this one are bound to be frustrating, however Priest’s delivery — the “cold factual language” combined with the slow eroding of the narrator’s control over the situation and his own narrative of his own role the experiment — creates a mesmerizing reading experience. But then again, I adore both The Affirmation (1981) and Barry N. Malzberg’s Beyond Apollo (1972).

For another view on the story see MPorcius here.

“All Pieces of a River Shore” (1970), short story by R. A. Lafferty, 4/5 (Good): Reviewed originally here.

At the very least R. A. Lafferty’s visions are always original and evocative… “All Pieces of a River Shore” contains Lafferty’s favorite tropes and narrative styles: Americana drenched Native American mythos, rural settings, unusual images… Leo Nation, a “rich Indian” (70) is obsessed with the Long Picture. Imagine a camera taking a panorama of the entire shoreline of a river. Unfortunately, fragments of this mysterious image printed on mysterious material taken (apparently) before humans had even evolved are scattered across the United States. Leo has a section that belonged to the “Arkansas Traveler Carnival” and was advertised as the “Longest Picture in the World” (72). Poor imitations of the panorama abound while some people used fragments of the real thing for ornaments and Indian medicine.

Slowly Leo realizes, as he acquires more and more pieces of this fantastic image, that it could not have been created by human hands. I found that the metaphysical and metaphorical dimensions of such a discovery are not explored enough by Lafferty.

“With Friends Like These…” (1971), short story by Alan Dean Foster, 2.75/5 (Vaguely Average): The first story I’ve read by Alan Dean Foster… It reminded me a lot of Poul Anderson’s “A Little Knowledge” in this collection—a somewhat tongue-in-cheek space opera which manages a few chuckles but little reflection other than humans will conquer and the galaxy can never stand in their way…. In the far future a galactic federation encounters an evil enemy, the Yops (who go around eating other aliens). The galactic federation needs help and so a spaceship sets off the find the mythical humans whom they fought in a past war. However, in the federation’s hard-fought victory, Earth was sealed by a powerful force field… When they land to recruit the humans for help, they discover that humans have radically evolved—and have untold powers. It’s funny and sort of cute. Ehh… not for me.

“Aunt Jennie’s Tonic” (1971), short story by Leonard Tushnet, 2/5 (Bad): Collection filler? I confess, I couldn’t finish this one. A Jewish-American scientists realizes that the tonic brewed by and old Yiddish immigrant named Aunt Jennie (“a witch or a saint. Or an ignorant old woman”) is a wonder drug… Of course, the possibility of greatness if he could take advantage of her recipe goes to his head.

“Timestorm” (1971), short story by Eddy C. Bertin, 3/5 (Average): Bertin is a German-born SF and horror writer who moved to The Netherlands and wrote primarily in Dutch whose work I’ve only recently become aware of. I reviewed “The City, Dying” (1968) a while ago and have a similar view of “Timestorm”—Bertin’s ambition to spin New Wave experiments does not match his skill in crafting them. “Timestorm” throws the unsuspecting Harvey Lonestall through a maelstrom of historical events and discombobulated realties. The cause: a “timestorm [that] began in another galaxy, too far away from our Sol even to be seen with the strongest telescopes” (227). The man: Lonestall lives in bland existence in a commercial laden world with four-day weekends. And anything written in the late 60s and early 70s with time travel (*cough* –> Malzberg) means Lonestall appears in Dallas on that fateful day…

Mimicking Lonestall’s own journey, the story is veritable whirlwind of ideas and big concepts—“was life artificially created here, or were the cylinders exact copies made after real life, but used to control and direct the originals” (235)—that never settles to speculates too deeply about anything in particular. It takes a strong and calculated hand to guide the reader successfully into a meaningful metaphysical descent—J. G. Ballard’s “The Overloaded Man” (1961) for example—and I’m not sure Bertin is up to the task.

“Transit of Earth” (1971), short story by Arthur C. Clarke, 4/5 (Good): A decade has passed since I’ve read a Clarke short story! (I reread Clarke’s Imperial Earth (1975) a while back and enjoyed it).

An astronaut narrator stranded on the moon reminisces about his doomed expedition waiting while waiting to observe the transit of Earth, a stupendous and infrequent astronomical occurrence… Clarke, of course, must tell the reader: “NOTE: All the astronomical events described in this story take place at the times state” (246). But it’s the theme of waiting for death and rationalizing death and placing one’s life in the grand scheme of things that really interests Clarke. The astronaut compares his own expedition to that of the doomed expedition of Robert Falcon Scott at the South Pole (1912). He ponders if and how he should take his own life…. “Transit of Earth” is an intense interior drama played out against the stark immensities of the solar system and its phenomena.

If you love a stranded astronaut story told with some real verve and power (and yes, with some obvious metaphors) then check this one out.

“Gehanna” (1971), short story by Barry N. Malzberg, 4/5 (Good): A slight but well-constructed story from one of my favorite authors…. Four characters. Four perspectives. Three lovers. A child. The New York subway system as a vast pulmonary network that ties each together and brings each apart. Each remembers the same scene in a distinct ways—but the subway remains the superstructure onto which the stories are woven. Articulate in its simplicity—rather understated for Malzberg…. Recommended.

“One Life, Furnished in Early Poverty” (1970), short story by Harlan Ellison, 4/5 (Good): Reviewed originally here.

A profoundly moving story of Gus Rosenthal—a foil for Ellison—who travels back in time and befriends his younger self. His younger self was ridiculed for being a Jew and ran away from home at a young age. Filled with autobiographical tidbits from Ellison’s own life, the work is interwoven with strands of nostalgia and longing to improve one’s own past.

“Occam’s Scalpel” (1971), novelette by Theodore Sturgeon, 3.25/5 (Vaguely Good): Overtly not SF… In some ways the story suggests how Sturgeon wants the world to view him: a literary author who uses the “SF” tidbits for literary purposes. In this case, the tidbit is a sham, the SF is not SF at all…. And the story itself is polished and functional but hardly artful or beautiful.

Two brothers meet in the night and discuss the life of Cleveland Wheeler who witnesses his boss’ cremation. The boss “seems” to be an alien. Wheeler promises to use his wealth to combat an alien scheme pioneered by his very own company to make the earth (through global warming and pollution) habitable for aliens. It’s all a scam. But a useful scam. The story suggests that the two brothers are part of the scheme. But the truth behind it all seems slightly outside the frame of the picture.

For more book reviews consult the INDEX.

Note: This collection contained work by three authors I had not read — Leonard Tushnet, Alan Dean Foster, and Stephen Tall. I know Alan Dean Foster became an incredibly prolific author. As all three put in poor shifts in this collection, what work of theirs should I keep an eye out for?

Joachim, we need to sit down and have many beers and discuss, among other things, statements like this: “…a literary author who uses the “SF” tidbits for literary purposes.” This statement directly implies that ‘literary fiction’ excludes science fiction. I would argue differently, precisely that literary fiction includes all genres and types. It is, in fact, the quality and originality of the individual work, and its focus on expressing some facet of the human condition which makes fiction ‘literary’. This can be done with romance and werewolves in the hands of the right author, thus I don’t perceive ‘realism’ (another ambiguous term in this context) as a gatekeeper… Beer…

Jesse, please read the rest of my statement: “In some ways the story suggests how Sturgeon wants the world to view him…..” I am not pronouncing any judgement on the matter as I care very little about these debates. I am also picking up on Wollheim’s mini-introduction to the story which of course can’t help but discuss how “literary” he is…..

🙂

Hmm, where to start. I read this anthology way, way back when it first appeared as a book club edition, can’t remember much about the stories though. Thoughts: Leonard Tushnet, was a prolific writer in the digests of the late sixties and the seventies. He was considered a humorist with a Jewish attitude. His stuff was readable, but it’s been thirty years. Malzeberg’s micro fictions, along with his contemporaries Steven Utley and James Sallis, seemed to clutter up the magazines of the sixties through the nineties. I never liked any of their fictions, and still don’t. Critics loved them, but readers didn’t. Never really liked Bertin, and recent re-readings of his weird fictions haven’t changed anything, Same is true for Foster, whose stuff was at least readable, Still, over the years his fiction has remained steadily pedestrian. Seems you agree. Even Foster’s novelizations are lackluster as he managed to make the Alien and Star Wars movies boring. Liked the Clarke story on a recent re-read. Never liked Russ, but over the years there has been a re-evaluation on my part, so color my younger self very wrong. Our tastes change over the years. I remember the early seventies when a friend of mine read everything by Clarke and Niven: he went into nuclear physics. Make of that what you will. Love the cover, it looks like an alien totem pole, but Schoenherr was primarily an outdoor and nature artist, so it figures. Thorough review.

I’m also not a fan of Sallis (I’ve not read Utley). Huge fan of Malzberg as you know. His work seems the opposite of clutter — it does a lot with very little….

And Russ is a master of her craft.

I was surprised that I enjoyed Clarke’s story so much. But contemplating death with the immensity of space as a backdrop is always a compelling theme.

Worth owning just for the cover alone. When I subscribed to Analog back in the 70s, I used to groan every time I saw one of John Schoenherr’s covers. Now I think he was their best artist. I didn’t buy too many of the Wollheim anthologies back in the day. After he and Terry Carr split up it seemed to me that most of the stories in their jointly edited anthologies must have been selected by Carr. There are some good stories in this book, but Carr’s books seemed to have top quality stories. And I think you’re being a little harsh on the ending of the Lafferty story. As a librarian, this story is one of my favorites of his and I think the suggestion given at the end is just enough information. Any more would have been overkill.

Yeah, I’m a fan of the cover. The image is a hi-res scan of my personal copy. But you are correct, I am more in the Carr camp of SF — Wollheim’s views on SF are too traditional for me.

I didn’t reread the Lafferty story so it’s fuzzy in my memory (I remember enjoying it at the time) — I copied and pasted my review from an earlier anthology (the link is provided above).

Evidently you misunderstood me. I said that Malzeberg’s fictions cluttered up the magazines when he was at his most prolific, not that his story’s were cluttered plotwise. Some recent re-readings of his stories have not lessened my dislike at all. It’s all a matter of taste. I also stated that I’m starting to reassess my dislike of Russ’ work, finding that I’m liking more and more of her stuff. Taste’s change, especially mine.

Oh I understood you, I chose to reinterpret your meaning of clutter by pointing out how he masterfully does so much with so little…. As in, he does the opposite of “clutter” up a magazine — he fills them with honed gems. You are essentially dismissing without the slightest reason the entire work one of my absolute favorite authors — so I’ll be a tad snarky about it. Hah.

Always happy to read these reviews. I will say, granting that I haven’t reread the stories in decades, I absolutely loved Niven’s “The Fourth Profession” — I think it’s one of his best 3 or 4 stories.

It’s also been a long time since I read Stephen Tall (real name Compton Crook), and I remember his stories being a bit baggy but fun.